Advertisement

Meet The Girls Who Code In A Roxbury Basement

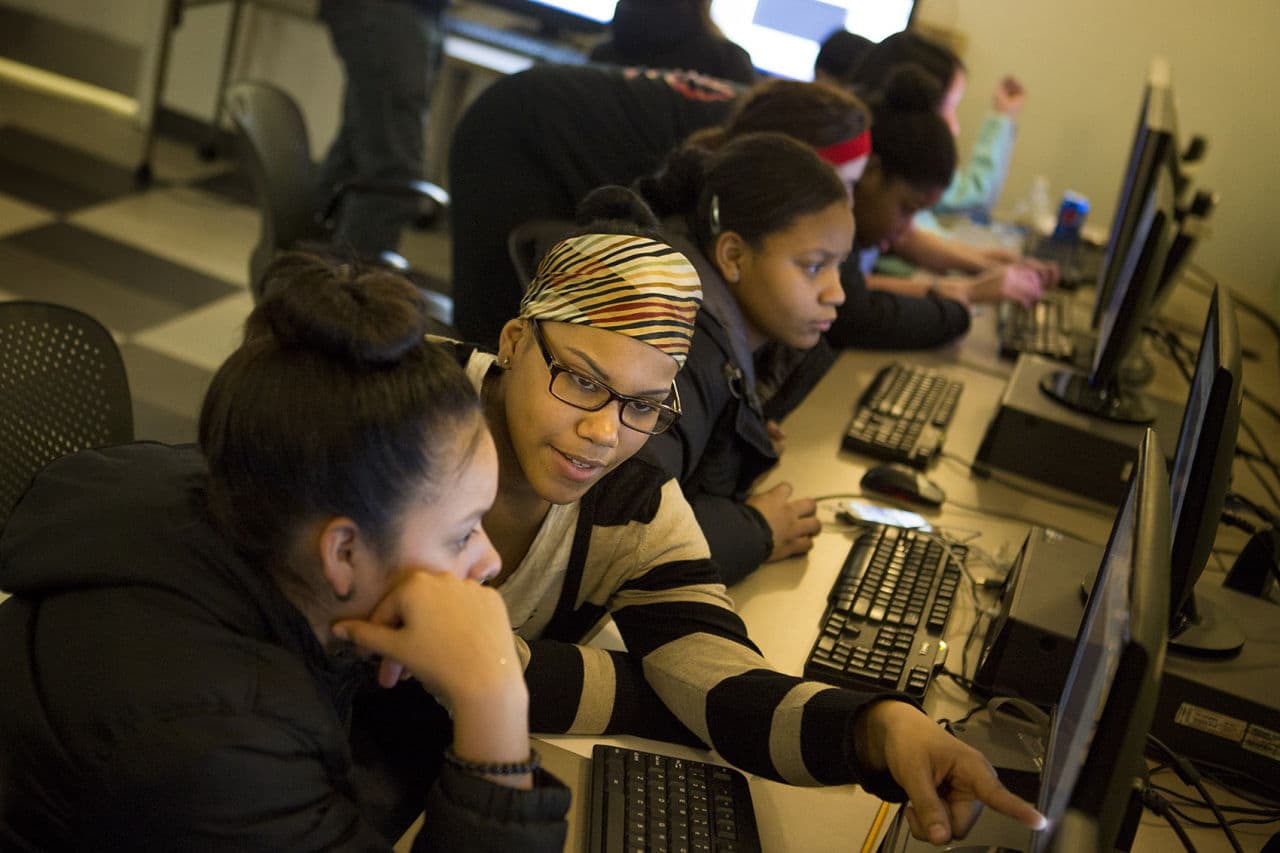

In a dimly lit basement room in Roxbury, a dozen girls stare into computer screens. There's a low murmur of conversation, punctuated by the occasional giggle, but mostly what you hear is typing.

It may not look like your idea of a homeless shelter. It also may not look like your idea of a classroom for computer programmers.

But it's both.

On Wednesday nights during the school year, the Brookview House Girls Who Code Club meets in this basement. It's the nation's only such club for homeless students, founded two years ago by the national nonprofit group Girls Who Code.

New Yorker Reshma Saujani founded Girls Who Code in 2012 with the hope that teaching computer skills to girls and young women would help close the gender gap in high tech.

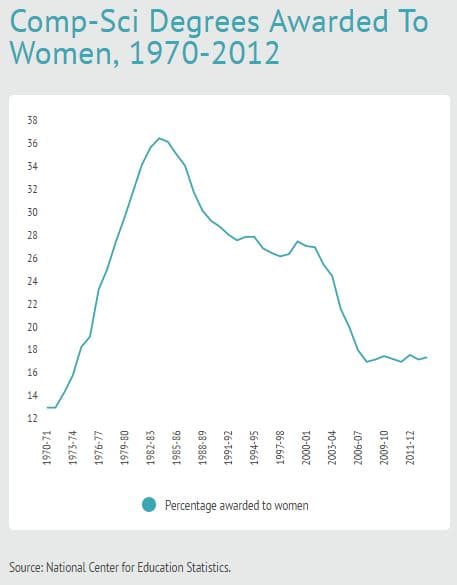

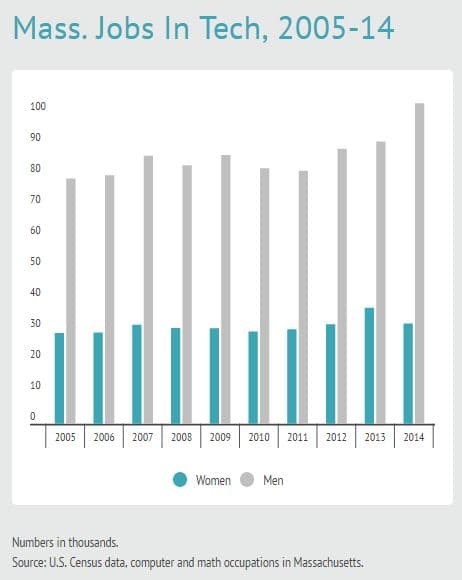

The gap is considerable. Just 18 percent of bachelor's degrees in computer science went to women in 2014. Women held just 29 percent of computer and math jobs in Massachusetts that year — and even that's slightly above the national average of 25 percent.

"I believe that technology can be the great equalizer," Saujani said in a phone interview.

Half the girls she works with live in poverty, she said, and "don't have computers at home, barely have working Wi-Fi in their schools. And they come to Girls Who Code, and within seven weeks they've learned a skill set that is going to help them and their families move up to the middle class."

Janae Bush-de la Cruz is one of these girls. She joined the Roxbury club when it opened two years ago.

Advertisement

Janae was living then at Brookview House, a Dorchester shelter for homeless women and their children. Her family recently moved into permanent housing, also run by Brookview. Happily for Janae, that new home is in the same Roxbury building where the coding club meets. So now she can just go downstairs.

"At first I thought it was going to be hard, because if you see the overview you just see numbers and it seems kind of difficult," Janae said. "But then when I actually got to learn it, it actually seemed pretty easy for me."

Janae, now 14, is a freshman at Fenway High School. Before she joined the club, she thought she’d become a hairdresser.

"My family, they're — no one has a really high, like, job right now. Well, not for me," she said. "I want to be something that no one else in my family is."

Now, she wants to be a doctor.

"I know if I was to become a doctor, computer science would help me a lot," Janae said. "Like patient information, if it’s inside of a computer, it’s easy to access. And I know how to go into which file and under which patient, and I know anything about a certain patient, because it’s all programmed to be figured out easily — thanks to computer science."

For now, Janae is working in a simple programming language called Scratch, which was developed at MIT to help students learn the basics of coding. High schoolers in Girls Who Code's clubs and summer programs also learn Python; some have gone on to build websites and apps, Saujani said.

In the basement, Janae stares at the cartoon-like little creature on her screen. She types a command. The creature doesn't respond as she expects.

"OK, so right now I am debugging," she says. "And now I have to figure out what is wrong. Even though it looks fine, it's not. I'm just getting frustrated."

"So click 'run' and hit the error message," says volunteer instructor Charity Leschinski, a software engineer. "And if it doesn't give you an error message, then ... yeah. Something's wrong. Little funk in the code."

The Girls Who Code organization supplies a curriculum and helps with instruction; it also arranges field trips to local tech companies. Host groups, like Brookview House, supply the computers, a site coordinator and, often, their own instructor.

The girls in the class receive a $50 stipend each month. "So it's just like the idea of, like, working," says Brookview's program director, Mayumi Brooks. And she gives the girls a substantial snack when they take a break halfway through the two-hour session.

The break also gives Brooks a chance to check in with each girl about her day, her schoolwork, any issues that are coming up in what are often challenging lives. In a soft voice, she asks each one in turn to say what she's learned tonight, how she's doing, whether she has any questions.

Leschinski reports that one girl is moving through the lessons quickly. Brooks beams.

"Alexis is the most advanced in the class? All right!" she exclaims. "I’m very proud of you. Because when you started you were just reluctant, like really, like 'I don’t wanna do this, I can’t do this.'" Everyone laughs at her imitation of a balky teenager. Brooks smiles. "And look at her now! Charity, remember? I — I’m proud of you."

The girls often start from a pretty low level of understanding, Leschinski says.

"It's really difficult to get into some of the computer science concepts," she says, "when they haven't had algebra or Boolean logic yet."

By the end of the school year, the girls will have worked through multiple lessons and will prepare a presentation to show Brooks and their parents what they've learned. They may also get to do more with corporate support; Brooks says Samsung and Cover Girl both held contests last year for which the girls created apps.

Saujani, the Girls Who Code founder, says some of the lessons are less tangible — but no less important. Through doing the work, she says, the girls learn that coding isn't just for boys. For one thing, it didn't start out that way.

"I mean, if you looked in, like, Steve Jobs' original Apple team, there's probably more women on it than there were on any technical team today," she said. "We were at parity, almost. It's shocking."

It's surprising but true. The original Macintosh team featured several prominent women -- including Susan Kare, who created many of the first screen icons, from the friendly little Mac face to the ominous bomb. Further back, some of the earliest computer programmers were women. Grace Hopper is one of the best known, but there were many more; the small team that programmed ENIAC, the first large-scale electronic computer, had six women.

"At first the programming seemed to be a routine, perhaps even menial task, which may have been why it was relegated to women, who back then were not encouraged to become engineers," the author Walter Isaacson wrote in 2014. "But what the women of ENIAC soon showed, and the men later came to understand, was that the programming of a computer could be just as significant as the design of its hardware."

Even into the 1980s, a significant number of computer science majors and programmers were women. In 1984, for example, 37 percent of bachelor's degrees in computer science went to women -- a far cry from the 18 percent in 2014.

So what happened?

"I think," Saujani said, "that in the '80s we marketed the personal computer to guys, we created this brogrammer, right, from 'Weird Science' to 'Revenge of the Nerds,' where it's like a guy wearing a hoodie in a basement and not showering, and girls are like, 'I don't wanna do that.' "

That didn't stop Charity Leschinski, the volunteer.

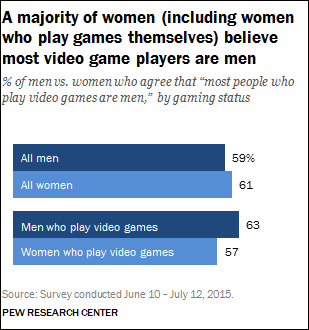

"For some reason, I liked video games," she said, "and that's how I got involved in coding."

That's how many coders get started. And here's where the brogrammer thing gets complicated. In surveys, most people — even those who play games themselves — say they think most gamers are male. The Entertainment Software Association says that's not true, that more women than teenage boys play games. Some studies suggest women play more on their phones, not the big consoles like an Xbox or PlayStation that you might picture when you think of video games.

Whatever the numbers, the image persists. So a lot of girls think computer games — and computers — aren't for them.

Janae Bush-de la Cruz knows better. She scoffs at the idea that anyone would think girls can't code.

"I can — we can," she says. "So ... people gotta change how they think about it, 'cause that’s not right."

Janae's fellow student, 14-year-old Shanice Escoffery, agrees. She's a freshman at Roxbury High, and one day a boy she knows there wanted to tag along to the club.

"And he was just looking, he was like, 'What's that? How do you do that? What is this?' " she recalls. "And then he actually asked, 'Can I join?' and I was like, 'Well, this is girls' coding, I don't know.' "

That was a great moment, she says.

"I mean, I could do a lot of things that he can't do, but it just felt even better."

Girls Who Code is indeed just for girls. And while no one seems to dispute that it helps girls learn computer skills, some women in the industry have said that's not enough to make a real shift in gender disparity.

"Creating an influx of new talent just to have them treated poorly in their workplace, under-compensated, marginalized or overlooked," wrote digital marketing consultant Lynette Young when Girls Who Code launched, "isn't really the future I want for my own daughter."

While she emphasized that she applauded efforts to get more girls interested in engineering and technical careers, Young wrote, "I also recognize the need to develop systems for women in these careers or businesses to stay involved."

But Saujani hopes her efforts will lead to lasting change. Just in its first three years, she said, Girls Who Code has taught 10,000 girls and young women the basics of coding. Her goal is to reach 1 million by 2020. And all of them, she hopes, will gain not just coding skills, but the confidence and new insights that come along with those abilities.

"Coding — everyone thinks it's a superpower," she said with a laugh. "And so when you feel like, 'I've learned how to code,' and you say to your mom or the girl sitting next to you, 'I know how that app is built, I know the logic behind how that was created' — that's powerful."

Janae Bush-de la Cruz says both her math and problem-solving skills have improved.

"It helps you just look deeper into things," she explains. "'Cause when there's a bug or whatever you have to look deeper. 'Cause bugs could be two spaces. It could be something so simple."

That's true for some adults, too. Brookview volunteer Jennifer Lam says the way she thinks as a programmer affects the way she thinks about life.

"It becomes a computer program, so you think about it like step 1, 2, 3, 4, 5."

For these girls, the next step might be a Girls Who Code summer program. (Boston will have five this year, according to the organization, to be hosted at Akamai, Microsoft, Verizon, TripAdvisor and Twitter.) Then high school courses. And then, maybe, a major in computer science. Saujani said two-thirds of the girls in her clubs — and almost all in the summer programs — plan to study computer science in college.

At a time when fewer than one in five computer science degrees go to women, that could start a revolution — or, as Saujani quipped, "world domination."

For now, the girls are in the basement, coding. And not necessarily only during class on Wednesday nights.

"We can always come back down here for another day, because it’s the afterschool program," Shanice says. "You can always come down if you want to code."

This segment aired on May 3, 2016.