Advertisement

Analysis: Joint Mass. And N.H. Presidential Primary Could Work

After an interminable and unwieldy presidential primary season, Republican party officials are considering major changes to their party’s nominating process in 2020.

The New York Times reports that one proposal would pair the traditional gatekeeper states of Iowa and New Hampshire with neighboring states "as a way to give more voters a meaningful role much sooner."

The traditional early states would still go first, but would not vote alone. In 2020, Minnesota would vote the same day as Iowa, and Massachusetts would join New Hampshire. In subsequent years, other neighboring states would be rotated in.

Though any proposal would provoke intense wrangling between state parties, pairing Massachusetts and New Hampshire makes a good deal of sense.

Gives Boost To Moderate States

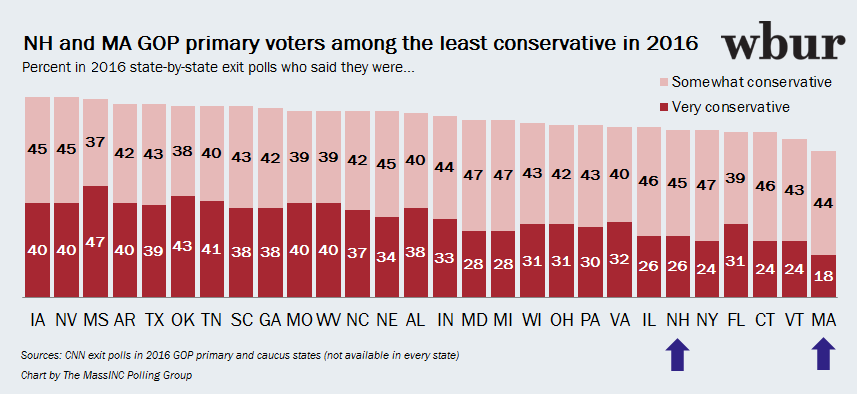

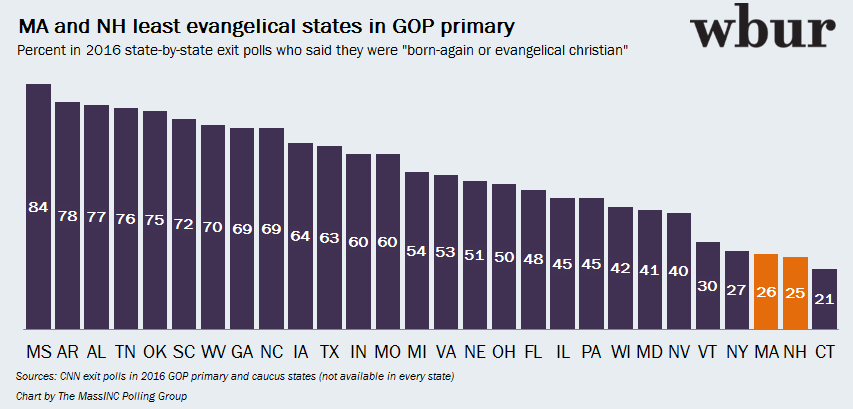

Adding Massachusetts to first-in-the-nation primary day would amplify the moderate wing of the party. At the moment, New Hampshire is the lone moderate representative among the first four states. A relatively low 71 percent of the state’s 2016 GOP primary voters call themselves conservative according to exit polls, and just a quarter said they were born again or evangelical. Both figures place the state among the least conservative electorates, as they have been in years past.

They also place New Hampshire very close to Massachusetts on the ideological spectrum of GOP primary states. Massachusetts was the least conservative GOP electorate this year, a repeat of 2008, the last time both parties held primaries.

Putting the natural pair together on the same day would give a moderate candidate a shot at two friendly states early in the calendar, and make it more worthwhile to camp out in New England early in the process.

Both states also have served as pretty good selectors of the eventual GOP nominees, choosing the eventual winner every time except 2008 in Massachusetts, when former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney edged eventual nominee John McCain. Winning the pair would be a real sign of strength for a candidate as the race gets underway.

Placing both at the front of the race and matching another state with Iowa would both serve to blunt the impact of the Hawkeye State’s increasingly futile caucus. Iowa, in recent years, has admirably represented the unelectable wing of the party, having voted for none of the last three party nominees (assuming Trump is it this year).

Iowa’s GOP caucus-goers have been the most conservative of any state in both of the last two election cycles, according to exit polls — and their votes show it. The last three caucus winners (Ted Cruz, Rick Santorum and Mike Huckabee) stood little chance of winning the nomination, much less the presidency.

There is nothing wrong, per se, with states consistently choosing losing candidates, and Iowa gives voice to voters who make up the right flank of the party faithful. But choosing to start the process in a state that fits this description is hard to understand.

But habits are hard to break, and diminishing the state’s impact by adding other early states could be the most realistic option for the party rather than trying to move it back in the schedule. Keeping Iowa early would also mean preserving the counterbalance to New Hampshire moderates, just with less ultimate impact on the early part of the process.

Preserves Benefit Of Small State Primaries

Putting Massachusetts and New Hampshire together also makes sense logistically. It answers the small state argument, that the current lead-off states work, because they are small, inexpensive and offer long-shot candidates a change to make their case face-to-face in small settings.

Massachusetts would add relatively little ground to cover, especially since most of the population is within driving distance of the New Hampshire border. Even this year, it was a bit of a mystery why more candidates didn’t pop over the border for a visit while blanketing New Hampshire. The Massachusetts GOP primary was a scant few weeks later, but received almost no attention until the last-minute.

The Boston media market also covers a significant area of southern New Hampshire, where most of the population lives. The additional expense of purchasing advertising would be somewhat tempered by this concentration. This year, Boston stations represented almost half of media buys targeted at the New Hampshire primary at one point. The Massachusetts electorate was already hearing the ads, they just didn’t get to vote until three weeks later.

This answers another common reason the New Hampshire primary is given special status. With few media markets in a smaller state, a less well-resourced candidate can potentially compete. But if the needed advertisements don’t change much by adding another state, this argument loses some utility. In fact, with so much Boston media purchased for the New Hampshire primary, it's worth considering a permanent pairing for the two states rather than just a temporary 2020 match. Massachusetts works very well as a partner to the New Hampshire primary, without adding a huge burden in terms of geography and expense.

New Hampshire and Iowa traditionalists also say the state’s voters take the responsibility of the first primary especially seriously, requiring candidates to visit, shake their hand, explain their positions and earn their votes in small settings. There is, by definition, no evidence this is correct, and some that it is not.

Since Iowa and New Hampshire have been first for decades, nobody else has had the opportunity to show their seriousness of purpose. Move another state to the front, and voters there may well respond the same way. And Donald Trump effectively destroyed this argument this year in New Hampshire, all but ignoring the tradition of face-to-face campaigning on his way to victory. John Kasich and Chris Christie all but moved to the state in the countdown to Primary Day and had comparatively little to show for it when the votes were counted.

But Will It Change The Outcome?

Moving Massachusetts up wouldn’t have changed the winner this year. Donald Trump won both New Hampshire and Massachusetts by wide margins. But the ideological spectrum was somewhat confounded this year by the constantly shifting positions of Donald Trump and his dominance over pretty much every part of the primary process.

In the future, the impact of this change could be greater in an election cycle with more traditionally measurable positions. If Trump is running for reelection in 2020, the order of states won’t matter unless he draws a serious primary challenger. But if the race is contested, moving Massachusetts up could benefit moderate candidates with less disruption than other potential changes to the schedule such as moving to a rotating regional primary system (also under consideration).

All of this ignores the all-out war Iowa and New Hampshire officials will launch if any change to their status is proposed. But joining the two offers clear benefits and answers many common concerns about changing New Hampshire's position.

Steve Koczela is president of the MassINC Polling Group and a regular contributor to WBUR Politicker. He tweets @skoczela.