Advertisement

Flawed Antihero Brings Us Behind Curtain Of Communist Hungary In 'Our Secrets' At ArtsEmerson

Everything old is new again?

“Our Secrets,” a show by Hungarian troupe Béla Pintér and Company, is set in 1980s Hungary and depicts the malevolent effects of an omnipresent state apparatus upon the lives of a group of avid folk dancers.

Several critics probably walked into the show, which is at the Paramount through Sunday, expecting to write florid thinkpieces extolling its contemporary relevance — the parallels between Cold War state surveillance and what many fear is omnipresent snooping by the National Security Agency today … not to mention Russian email hacking. Maybe some will. ArtsEmerson, which brought the show here as part of a short tour that also takes it to the Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York, certainly played up that angle in promotional materials that feature warnings about government surveillance by Edward Snowden.

But earlier this month when I had the chance to interview Pintér, who wrote, directed and acts in the show, I lobbed what I thought was a softball question giving him the chance to expound upon its contemporary relevance and he declined to do so. His focus, he said, is more narrowly focused: on life behind the Iron Curtain and the fact that a public list of collaborators with the Hungarian secret police has not been released. He has old scores to settle.

The backward glare of this sometimes-thoughtful, sometimes-strident show is indeed pronounced, and its political commentary is actually the least nuanced and least compelling part of the proceedings. Its psychological depth, too, is hampered by authorial conceit.

In a bold artistic gambit, Pintér gets at all this through the story of a pedophile whose secret is discovered by the police and used to compel him to inform on his folk-dancing friends. When we first see István Balla Bán (played by a very good Zoltán Friedenthal), his shoulders are hunched with guilt as he confesses his sexual desire for his wife’s 7-year-old daughter, but insists that he’s never acted on it. The audience is given every encouragement to extend empathy toward István — and then that good faith is almost immediately betrayed when we discover the extent of his wrongdoing. Pintér’s brio here is admirable.

István is a very flawed antihero who is nevertheless the heart of the play. His story is complicated further in an extremely strange dream sequence, featuring a breastfeeding Michael Jackson, that suggests the source of István’s sexual dysfunction. The push and pull with audience expectations is fascinating and commendable.

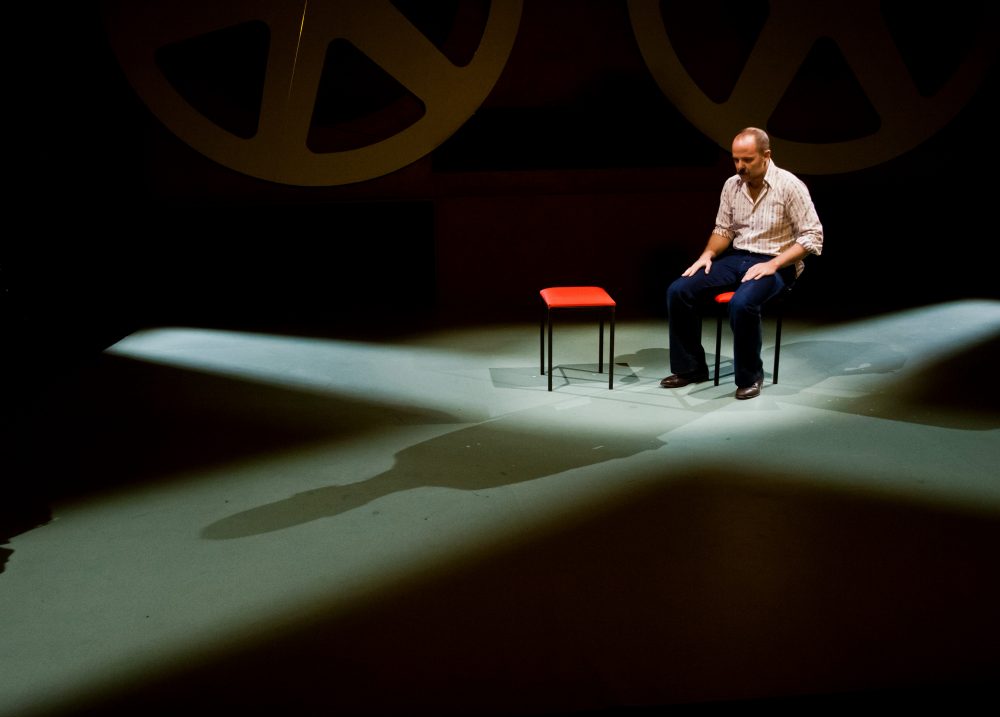

In a heavy-handed but effective directorial touch, the set is dominated by an oversized facsimile of a tape recorder, its reels spinning as a looming reminder that the walls have ears. This setpiece also figures heavily into a potently effective sequence in which a blaring pop song warping in and out of proper tempo builds tension and a sense of the uncanny. In other moments, Pintér presents his 13-person ensemble, including three onstage musicians, in tableaux that suggest archival scenes of black and white film footage.

The actors perform in Hungarian, with supertitles providing an often-clunky translation. Last season ArtsEmerson presented shows performed in Russian, Polish and Spanish. “Our Secrets” lacks the visceral power of seeing Chekhov in the original Russian, but this is still a valuable experiment that I hope will continue. The audience chuckled at some inappropriate moments early on, such as when István makes a pained face after his wife (played by a strong Hella Roszik) tells him to make sure her daughter cleans herself thoroughly in the bath. I wonder if the distancing effect of reading the dialogue (rather than hearing it) encourages these off-tone moments.

István's journey is interesting, though it feels a little too manipulated for artistic effect. This is a world where children skip away happily after being sexually assaulted, unaware that anything is wrong. Communist Party officials, who know about his pedophilia, make social overtures to emphasize to the audience the benefits of collaboration with the state. Are these details based on research into the realities of sexual abuse and of Communist rule, or concocted to complicate the protagonist’s story? For a piece that seems to promise social realism, many moments land oddly.

Pintér figures as Imre Tatár, a secret dissident in a relationship with an ardent Communist named Bea Zakariás (an effective Zsófia Szamosi). Their interplay does not ring true, and Imre’s motivations in the context of this love story are hard to determine. Angéla Stefanovics is convincing as Imre’s young son Ferenc, a reserved musical prodigy, and Eszter Csákányi is likable in a scene as István’s psychiatrist before doubling as a Party agent.

In a ham-handed postscript, anti-government fervor is represented by an argument over government funding for one arts program versus another. It serves for some mechanical exposition about the fate of some characters, and for Pintér to express his chief complaint: "In 70 years, everything that’s now confidential will be revealed and publicly announced! No need to care about all this ‘till then,” an authority figure chortles.

But for those looking for a haunting statement about the dangers of government overreach, the play closes with a sung couplet apparently taken from a folk song: “This tale has now been fully told: There’s nothing new; there’s nothing old.”