Advertisement

How Fred Eversley Went From NASA Engineer To Cosmic Artist In '60s LA

It wasn’t clear that night in January 1967 when Fred Eversley walked out of work that he was heading toward a turning point in his life. He was a rocket scientist — technically a senior instrumentation engineer for the aerospace firm Wyle Laboratories in El Segundo, California — designing and supervising construction of testing facilities for NASA’s Gemini and Apollo programs, the work leading up to the moon landings beginning two years later.

But by the end of 1967, Eversley would instead be on the path to becoming a major sculptor, known for creating translucent plastic discs, concave on one side like lenses, with hues of violet and amber and blue that can bring to mind sunsets and outer space.

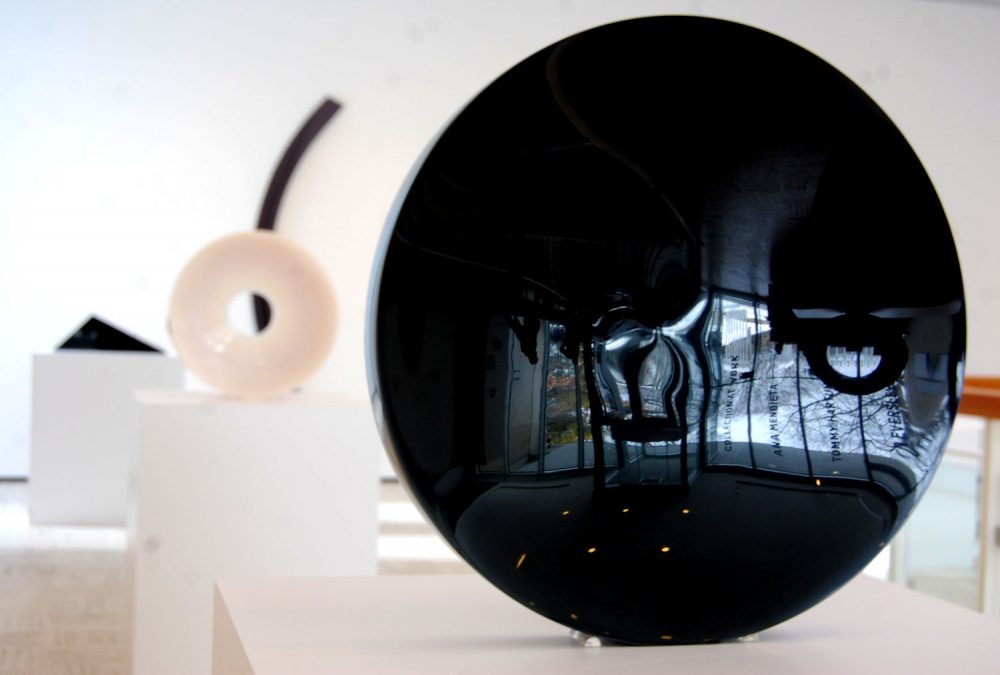

His very first solo exhibition would be at New York’s prestigious Whitney Museum of American Art in 1970. He’d be named the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s first artist-in-residence in 1977. Today, his sculptures are recorded in art history books and featured in the collections of museums all across the country. And he’s now the subject of “Fred Eversley: Black, White, Gray,” an exhibition at Brandeis University’s Rose Art Museum in Waltham through June 11.

But on that January night in 1967, Eversely had just returned to Los Angeles after celebrating the holidays in New York, where he grew up. He had gotten a big promotion, so he’d bought himself a new three-piece suit that he was wearing on his first day back to work.

He oversaw dozens of people on projects that did things like create labs to blast the components of spacecraft with intense sound to mimic the environment of space, especially the ship’s screaming reentry into earth’s atmosphere. He regularly worked long days, but to catch up after being off for two weeks, this day he put in an especially long day of 14 hours. He finally went out into the parking lot to head home around 11:30 that night. Only two cars were left: the company president’s Aston Martin and “my funky MG.”

But his car’s engine wouldn’t start. So he attempted a “push start,” sitting at the steering wheel with his foot hanging out of the open driver’s door to push against the pavement, hoping the forward motion would help the engine catch. It slipped his mind that there was a telephone pole in the parking lot. Until his door crashed into it.

“It closed the open door on my leg, breaking my leg and thigh,” Eversley recalls. “I couldn’t control the car. It rolled to the edge of the parking lot, then down a gully and out of view.”

“I came very, very close to dying,” he says. He blinked the headlights and honked the MG's horn trying to get someone’s — anyone’s — attention. After some time, the company president, Frank Wyle, returned from a card game with company vice presidents and, luckily, was sober enough to realize something was terribly wrong.

Wyle called the fire department. “They took me to the local county hospital where the doctor on-call never answered the call to come in and the nurse wouldn’t give me anything,” Eversley says. So he called his (then) girlfriend, who got back in touch with Wyle, who called his own orthopedic surgeon, waking him up at his Beverly Hills home around 3 in the morning. They moved Eversley to Cedars-Sinai Hospital.

Advertisement

“We’ll save your life,” the doctor told him. “We’re not sure we can save your leg.”

‘I Was Always Interested In Energy’

Science and engineering ran in Eversley’s family.

Fred Eversley was born in 1941, the oldest of four siblings, and grew up in Brooklyn and Queens, New York. His ancestry includes African-Americans, German Jews, Shinnecock Indians and the son of Martha Washington.

His mother, Beatrice, was a New York schoolteacher. Her father, John Syphax, who lived nearby, was a pioneer of photography and an inventor, who kept around old radios and other gadgets from the 1910s and ‘20s that fascinated Eversley as a boy.

Eversley’s father, Frederick W. Eversley Jr., was born in Barbados, moved to New York with his family when he was 3, rose to develop jet airplanes and then make headlines as the “black contractor” named “engineer-of-the-year.” He ran “one of the largest construction businesses with minority-group ownership in the New York area,” according to The New York Times. They built banks, churches, apartment buildings, an IBM factory, and an exhibit at the Bronx Zoo that was home to nocturnal animals.

“I always had a large workshop where I did my experiments in the basement of my parents’ house,” Eversley says. “I was always interested in energy — wind energy, water energy, solar energy.” He got an amateur radio license at age 8 and used it to converse with people about science, radio and photography via Morse code. He attended Brooklyn Tech High School, then studied electrical engineering at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, graduating in 1963.

“I never sat in classrooms with a kid of a minority of any sort from kindergarten to university,” Eversley says. “The whole time I was an engineer, I never worked with another black engineer ever. … I was the only black in my corporation.”

After finishing at Carnegie Mellon, Eversley planned to study bio-medical engineering at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. But his (then) girlfriend had signed up to study painting in Mexico. He craved to spend the summer with her, but his parents were against it and wouldn’t provide travel money.

One of his college fraternity brothers was the son of Frank Wyle, the president of the California aerospace engineering firm Wyle Laboratories. “In desperation,” he called the company executive and asked for a financial advance in exchange for pledging to work for his firm for six to 12 months. “If you’re schmuck enough to do it, I’m schmuck enough to send you the money,” Eversley recalls Wyle telling him.

So Eversley tagged along with his girlfriend and pretended to study mural painting. “I went and looked at the wall almost every day,” he says. “I never did a thing. But at the end of the day, I signed the wall.”

Venice Beach

Eversley arrived in Los Angeles in 1964 and began working with Wyle Laboratories on projects for the French atomic energy commission, the European space agency, a U.S. weapons lab in Virginia, and NASA.

With a Jewish friend, he tried to find a place where they could live together. His roommate would go out during the day and track down five or six possible rentals, but when Eversley went back with him in the evening, suddenly all the places were no longer available. A white co-worker finally clued him in — the problem was racist landlords didn’t want to rent to the African-American engineer.

So they ended up in Venice Beach. “It was the only beachfront community I was able to rent in,” Eversley says. “It was the only integrated beach community.”

“Venice Beach in those days was basically Greenwich Village moved west,” Eversley says. “It was the remnants of the Beats and jazz people, John Coltrane and Miles Davis. Dexter Gordon had already split from his wife and moved to Denmark, but his ex-wife and two daughters lived right next to me.”

The neighborhood was also home to Jim Morrison and other members of the band The Doors (Morrison wrote the first drafts of “The End” while hiding out under the nearby Santa Monica Pier) as well as blues guitarist Taj Mahal and the band Canned Heat. “Everyone went passing through, including Janis Joplin,” Eversley says. “In spare time that I had and on weekends, I’d hang out with my neighbors, including [artists] Larry Bell, Jim Turrell, Ed Moses, Bob Irwin, as well as John McCracken, John Altoon and Charles Mattox. And as an engineer, I would help them do little things, technical things.”

The Los Angeles art scene was on the rise in the 1960s. Rico Lebrun, whom Everesley was introduced to by the Wyles when he moved to California, gained prominence there as a cubist-inspired, “abject expressionist” painter (in curator Michael Duncan’s artful phrasing) in the decade following World War II. (Lebrun also tutored Disney animators in drawing, especially those working on “Bambi.”) During the 1950s, flat, hard-edged, geometric abstract painting by John McLaughlin, Lorser Feitelson and Helen Lundeberg came to the fore. But all of these artists struggled to gain notice outside California.

That began to shift in the 1960s as California artists developed pop and minimalist styles with a local flavor influenced by the local climate, custom car culture, surfing, Hollywood, Disneyland, and the new plastics coming out of the aerospace industry that arose along the West Coast to fight World War II and continued to thrive during the Cold War — and employ Eversley.

Venice Beach, “to be there, in ’67, ’68, ’69, with what’s going on in the world, I imagine that place being freedom,” says Kim Conaty, the Rose Art Museum curator who organized “Fred Eversley: Black, White, Gray.” Eversley “talks about the energy, but he also says you could do everything. Rent was really cheap. You could try something and fail and be OK.”

In studios in Venice Beach and next door in Santa Monica, Robert Irwin and James Turrell pioneered what became known as “Light and Space” art, making sculptures and installations in which the objects seemed to dematerialize, becoming immersive environments of light and shadow and glowing color. Larry Bell moved from painting geometric abstractions to fashioning glass and mirror cubes. Moses made abstract paintings. McCracken crafted resin-coated planks that looked like they’d just been dipped in glossy paint — part of what became known as “Finish Fetish” art. Altoon made paintings that could be the love child of Arshile Gorky’s doodley surrealist abstractions and Playboy cartoons. Mattox constructed kinetic sculptures — mechanical devices that moved — such as a box with L-shaped bars on top that rocked back and forth.

Ideas cross-pollinated through this Venice Beach art world of ambitious white guys (one 1964 group exhibition including Irwin and Moses was called “The Studs”) as they chatted and taught each other skills and competed. And the world — outside California, in New York even — began to take notice. The Ferus Gallery, Dwan Gallery and the Pasadena Art Museum championed new California art and brought in prominent New York and French modernists — creating relationships among artists, curators and collectors that helped raise the international profile of the Californians.

Eversely rubbed shoulders with these artists at studios, exhibition openings and museum receptions. There he met major New York artists — Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Carl Andre — and collectors. “LA is small. So all the museum directors, all the museum curators are all at these parties,” he says.

After these bohemian escapades, Eversley says, “I put on a tie and jacket every day and went to the office.”

The First Technologist

Which is where he was when he crashed his car and broke his leg on that night in January 1967. The surgeon thought he could save Eversley’s life, but maybe not his leg.

Eversley says, “They managed to save both.”

His injuries left him on crutches for 13 months. “The moment I had my accident, Charles [Mattox] said, ‘Why don’t you move into my loft.’ He had an empty loft in his studio. ‘I’ll give you free rent for helping me with my art.’ His [kinetic] sculptures were famous for falling apart,” Eversley jokes.

Inspired by the Experiments in Art and Technology project that Rauschenberg and engineer Billy Kluver started in New York, Mattox had launched similar collaborations between artists and scientists. Eversley says, “I was the first technologist.”

“My [Wyle] job kept me out of Vietnam — critical skills deferment,” Eversley notes. The year of recovery from the accident, “took me over my 26th birthday, which took me past the magic age in those days not to be drafted.”

So he left Wyle, moved in with Mattox, and began making art — “experiments,” he called them. He cast resin into rectangles with photos and electronics embedded inside. “I was transmitting the energy to these flat rectangles by way of radio waves,” Eversley says. “While I was at NASA, I got this enormous box of rejects, these miniature neon lights that were made for Apollo that were perfectly fine except they didn’t meet the rigid requirements for space. … When I transmitted radio energy at them, they glowed.”

But he had trouble making the electronics work consistently and “I couldn’t nicely embed the photos into the plastic,” he says. Altoon and McCracken, who had studios nearby, would stop by “with some little problems” that he would help them sort out. He showed them what he was working on. “Forget the electronics. Forget the photographs,” Altoon said. “Those little pieces of yours are fantastic.”

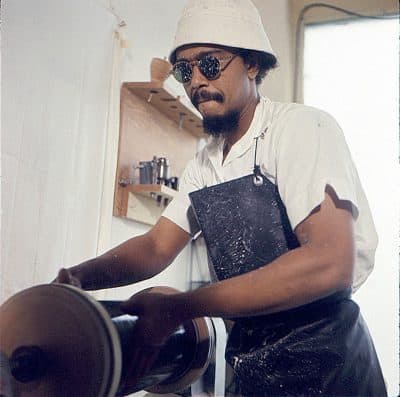

Six months after Eversley moved into Mattox’s studio, Mattox left for Albuquerque, to teach at the University of New Mexico, “and he never came back.” With the space to himself, Eversley focused on casting his resin sculptures. He moved onto space-capsule shapes. Then he cast resin inside a foot-wide pipe he spun around a horizontal axis on Mattox’s lathe. “I pour in liquid plastic and I cast a tube,” Eversley says. The centripetal forces pushed the resin to the outside of the pipe. He cast it in layers, from the outside in -- violet, amber, blue.

“When they’re first cast, they almost look like soap. They’re really, really rough,” Conaty says. Eversley sanded and polished them until they gleamed. “The difficult part,” he says, “is the polishing, which is 99 percent of the work.”

Sometimes he left the sculptures as tubes, sometimes he sliced them thinly to create translucent, curved wedges. “That work is the basis for my first one-man show at the Whitney in ’70,” Eversley says. “And immediately after that I started experimenting — well, I had been trying — in casting about the vertical axis.”

Eversley’s studio neighbor Altoon died from a heart attack at age 43 in early 1969, and his widow Babs let Eversley take over the lease of his studio, just a few blocks from the beach, with its interior designed by their friend, the (now) celebrated architect Frank Gehry. (“I’m still there,” Eversley says. “It’s still a rental.”)

Working and living there, Eversley rigged a variable-speed motor to a potter’s wheel, allowing him to spin his castings around a vertical axis and create shapes with larger diameters. Out of this he developed his signature sculptures — translucent discs of radiant color.

They’re usually about 20 inches across and up to 7 inches deep, flat on one side and concave on the other, sometimes with the resin thinning to a hole in the center. With their saturated hues — deep blues, reds, yellows, amber browns — and holes, they can bring to mind giant Life Savers candy.

“They’re fascinating as these engineered things,” Conaty says. But they’re also “jewel like. … It’s basically plastic, but he creates these lens-like sculptures that are intimate in a way, that are human scale, that encourage you to look and see yourself reflected in them.”

“A lot of people see them as these sci-fi objects, these orbs,” Conaty says.

“Going from the horizontal to the vertical allowed me to create perfect parabolic shapes,” Eversley says. “The parabola happens to be the only mathematic shape that concentrates all forms of known energy to the same single focal point.”

“I’ve always been interested in the subject of energy, in the narrow scientific sense and in the broader metaphysical sense,” Eversley says. “Don’t forget the ‘60s and the ‘70s were the New Age years. So I was surrounded by the I Ching and this and that. I did everything everyone around me did.”

Eversley goes on, “The beach” — Venice Beach — “is all about energy. It’s the wind, the rain, the sun, the waves. You’re surrounded by the presence of energy. You’re also surrounded by everyone who comes to the beach, which ends up being — with very few exceptions — in a very positive, energetic state.”

“I’m not claiming it was even all that conscious,” Eversley says. “All the artists that lived in that atmosphere — [the painter] Richard Diebenkorn with his stuff — everyone if you thought of it, the beach influenced them. The musicians sat on the beach and blew out sounds to the sunset and they blew out some positive sounds. … I had all my scientific knowledge and all my years of sitting in my parents’ basement laboratory and Carnegie Mellon, but you’re in this atmosphere with that background. I always considered that energy and how to harness that energy to make people happy.”

Make Some Black Art

Eversley’s sculptures are often grouped with the “Finish Fetish” and “Light and Space” art emerging from Venice Beach — art that has been seen as apolitical. But Los Angeles artists were also producing some of the most politically charged American art of the 1960s and ‘70s.

Betye Saar, David Hammons, Senga Nengudi, John Outterbridge, Noah Purifoy and other African-American artists around Los Angeles recycled found materials into assemblage sculptures — some of them even salvaging wreckage from the six-day Watts Rebellion/Riots in 1965 — that spoke about racism, civil rights and being black.

These artworks were cousins to the assemblage sculptures Ed Kienholz, Wallace Berman, Bruce Conner and other white California artists had been making since the 1950s — often addressing the politics of the time, from fears of nuclear annihilation (part of what California’s aerospace industry was working on) to illegal, back alley abortions. The nun Sister Corita Kent riled Los Angeles’ Roman Catholic leadership with pop art screenprints that celebrated her faith, opposed the Vietnam war, and pushed for civil rights. Los Angeles was one of the birthplaces of feminist art, with artists Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro launching the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, just north of LA, in 1971.

In his art, Eversley generally remained apart from these political developments, despite social pressure to be more obviously engaged. Instead he was in a category with Al Loving and Sam Gilliam — the rare African-American artists of the 1960s and ‘70s who found success in abstraction. To this day, it remains unusual for the top echelons of the white-dominated Western fine art world to embrace artists of color if they don’t make art that speaks about their racial identities.

Eversley has long and strongly resisted being pigeonholed as an African-American artist. “There’s certainly been criticism of me for not making art that talks about the black experience. ... I just keep doing what I do,” he says. “It’s not about being black.”

But in 1972, Eversley left the reds and violets and amber hues behind for a time and began making black discs, the starting point for his “Black, White, Gray” exhibition at Brandeis’ Rose Art Museum. He “began to explore the qualities and beauty of the color black,” Conaty writes.

Eversley says he arrived at his initial violets and ambers by chance: “They’re arbitrary colors. Two of the colors had been sitting on the shelf in Charlie’s studio when I walked in the door. I think I bought one more, the blue.”

His black sculptures, he says, began as a sort of joke about the pressure for him to make art about being African-American. “John McCracken at the time was doing black planks and decided he had made black sculptures long enough and he gave me has can [of black pigment],” Eversley says. “McCracken said, ‘You’re being heavily criticized for not making black art. Make some black art.’”

“When he gave me that can, I didn’t use it the next day,” Eversley says. “It sat there for a year. My first [black] piece, I used it because I messed up a casting and I wanted to save the work. But it came out very interesting.”

The black was luxurious and glimmering and sensual. Conaty says, “There was a real magic in the black that he hadn’t anticipated.”

“It’s totally different because it’s no longer transparent,” Eversley says. “Now you’re dealing with a mirror, with some translucency in the center, but basically a mirror.”

He’d done four or five black pieces and then, so the story goes, when his white studio assistant joked that he should make white ones too for white folks, Eversley began making milky white discs. And then cloudy gray ones too because, he jokes, “I’m half black and half white.”

So black and white and gray are just a gag?

Eversley says he was also thinking in cosmic terms, but not about race: “I was very much talking about black holes and white dwarfs.”

But Conaty says, “There is absolutely a component to those works that relates to identity.”

The sculptures seem to ask: How do you attribute meaning to color? They seem to ask: When an African-American artist uses the color black, must you see it in terms of race?

“When he made the first good black lens, some people who knew him began to say, ‘Whether you understand it or not, these are your most important works,’” Conaty says. “I think he recognized the power of color, how people read it, how it resonates with their expectations, and how he might play with that."