Advertisement

Rediscovering Baroque Master Carlo Dolci, Whose Paintings Bring Emotions Right To The Surface

“Should you want to see Carlino’s conscience — delicate, accurate and diligent as it was — you need only observe the works from his brush,” the painter Carlo Dolci’s spiritual adviser is reputed to have said.

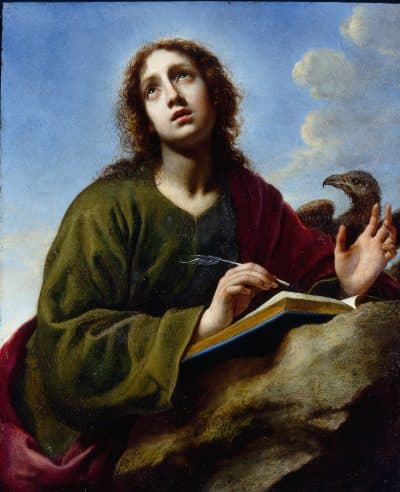

In the paintings of Dolci (1616-1687), there are tender moments between holy mothers and children, and Roman Catholic saints gaze up to the heavens or turn their eyes down in deep thought or holy supplication. His people are often overcome with ecstatic emotion. Elizabeth, the mother of Jesus’ cousin; Apollonia, the patron saint of dentistry; and Mary Magdalene, whom the Bible says was healed by Jesus and then became the first to see him after he rose from the dead after his execution, raise their hands to their chests in astonishment, as if their hearts can barely weather such passionate feelings. These are scenes of rapture and swooning, tears and blood.

Dolci was the “premier artist” of 17th century Florence, writes Eve Straussman-Pflanzer, the curator of “The Medici’s Painter: Carlo Dolci and 17th-Century Florence” at Wellesley College’s Davis Museum through July 9. The exhibition, billed as the “first exhibition in America devoted” to Dolci, assembles 52 of his paintings and drawings, about a quarter of his surviving artworks.

Dolci “made a firm resolution to paint only sacred images and sacred stories, realized in a manner that would elicit Christian piety in those who admired them,” the artist’s friend and biographer, Filippo Baldinucci, wrote. “It was difficult to tell whether he was more excellent in the art of painting … or in living a good [Christian] life.”

Consider Dolci’s “The Penitent Magdalene” from the 1670s. She leans forward, hands folded in prayer, gazing up in anguish, a tear on her cheek. Dolci likes to depict his saints one at a time, situated forward in the frame — making them feel physically close to us, in our space, amplifying the emotions because he has carefully eliminated nearly everything else.

The Wellesley exhibition is part of an effort to boost Dolci’s reputation. The Italian painter was a favorite of American Founding Father Thomas Jefferson (“nothing human was ever so beautiful, so heavenly”) and author Nathaniel Hawthorne (“a miracle of pictorial art”), but has often been overlooked by British and American art historians because he doesn’t fit neatly into the story historians have crafted for baroque art (he doesn’t paint enough grand narratives and sweeping allegories) and they find his passionate canvases, well, unsophisticated. But this seems to miss the point. What Dolci offers is intimacy and rapturous feeling.

“He was a very delicate soul, so psychologically sensitive. He had a lot of psychological breakdowns,” says Straussman-Pflanzer, who is head of the European Art Department at the Detroit Institute of Arts and previously a senior curator at the Davis Museum.

According to Baldinucci, Dolci had an “obsession with failure. At times, it took almost a physical effort to get him up and out of his house.” He had an “unrelenting melancholy” spirit,” deriving from a pusillanimous, timid, and reflective nature.”

Dolci married at age 38 — quite late for his era — to a much younger woman. “On the morning when Carlino was meant to present the ring to his bride, everything had been prepared an the relatives had gathered in the assigned place. All that was missing was the groom,” Baldinucci wrote. They finally found him praying in the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata (Basilica of the Most Holy Annunciation).

One of Dolci’s masterpieces is his allegorical painting of “Poetry” from the 1640s. Rather than imagining poetry as a naked lady dancing across an enchanted garden, as his peers might have done, Dolci depicts poetry as a beautiful woman, crowned with laurel leaves, wearing a gown that rises right up to the base of her neck. She stares serenely out at us.

“I don’t think he was that comfortable with his ‘natural’ reactions from his body,” Straussman-Pflanzer says. Though that didn’t stop him from having at least seven children.

Dolci paintings are both intimate and theatrical, like orchids carefully nurtured to blossom in a hothouse. He highlights people’s gestures, their acting, as they seem to be caught in spotlights amidst dark spaces and backdrops of moody clouds. One can imagine the people in his paintings seeming like apparitions when displayed in 17th century candlelit chapels.

In his earliest efforts, Dolci’s brushwork was somewhat rough, the flesh could feel waxy or wooden. But with practice, he became known for his meticulous, polished realism and exquisite craft. Skin often seems to shimmer. For models, he turned to family members and friends — and art.

In the 1650s, Dolci spent some eight years painting his copy of a famed 14th century “Annunciation” on a commission from nuns. It is a classic Catholic motif, depicting an angel visiting Mary to announce that she would become the mother of Jesus, the “Son of God.” Dolci prepared by drawing numerous preparatory studies. Baldinucci reports that observers found the jewels in Mary’s crown were “imitated in a manner so stupendous” that many observers felt the need to touch the canvas to assure themselves that they were actually painted.