Advertisement

Our Guide To The Art Inside MASS MoCA’s Gigantic New Building 6

Resume

NORTH ADAMS, Mass. — Since the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) opened in the old Sprague Electric factory in North Adams in 1999, it’s become known for its vast industrial spaces that it fills with monumental art. The museum has expanded as it slowly redeveloped the 16-acre, 26-building site. Now with the debut of its Building 6 on Sunday, May 28, MASS MoCA adds 130,000 more square feet of space, nearly doubling its already enormous room for exhibitions — one of the largest in the country.

To get a sense of the scale of the undertaking, one of the first things you see when you enter Building 6 is an eye-popping mural by Boston artist Joe Wardwell that’s 140 feet long — about the size of a 14-story building laid on its side.

Building 6’s triangular footprint, nestled at the confluence of the north and south branches of the Hoosic River, has been given over to new, large, long-term exhibitions of transcendental light installations, eccentric instruments visitors can play, bracing ruminations on America’s recent wars, and immersive virtual reality experiences by names including James Turrell, Laurie Anderson, Jenny Holzer, Gunnar Schonbeck, Robert Rauschenberg and Louise Bourgeois.

To help you find your way, below is our guide to Building 6’s highlights:

James Turrell

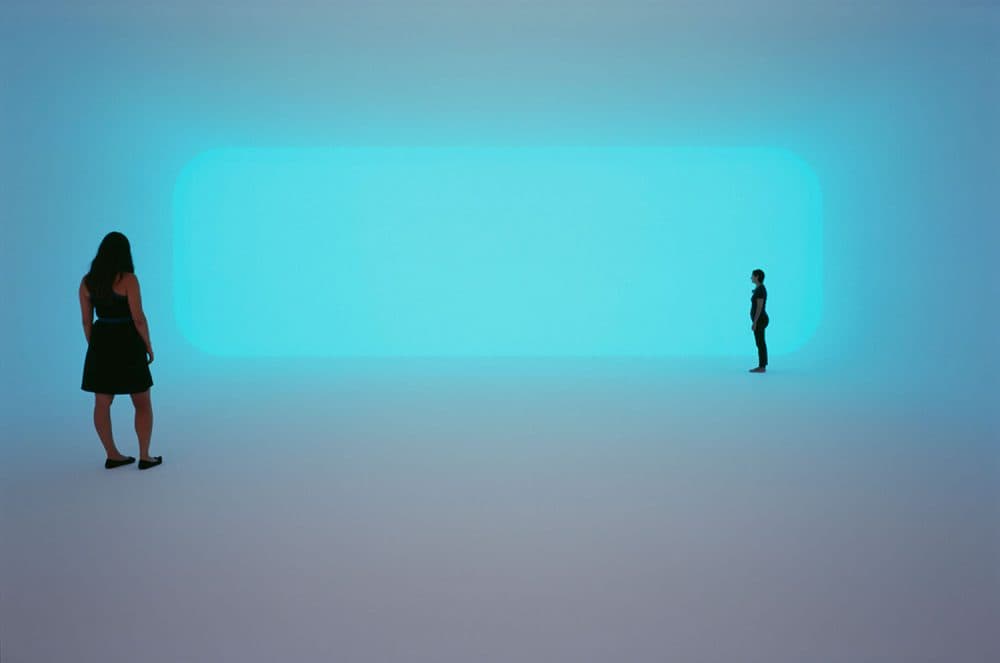

“Imagine closing your eyes, but instead of seeing blackness, you’re washed with color space,” MASS MoCA director Joseph Thompson says in a valiant attempt to describe one of James Turrell’s wondrous light installations.

Turrell, who now splits his time between Maryland and Arizona, is one of the most astonishing and important artists to emerge from Los Angeles in the 1960s. He was part of what’s called the Light and Space movement, a group of artists who altered exhibition spaces to create works operating at the very edges of our senses of perception. But it remains rare to find Turrell’s art east of the Rocky Mountains.

Another aspect that helps make Building 6 a new art pilgrimage destination is that nine rooms have been meticulously constructed for Turrell’s signature mind-blowing mirages. Featuring a retrospective of designs dating back to 1967, on view here as part of a 25-year partnership, this is a rare occasion where “mind-blowing” is actually not hype.

In some installations here from the 1970s, you walk into find rectangles or diamond shapes on walls. At first they appear flat, but as you walk closer they feel … strange. As if they’re humming or vibrating. Try to touch them and your hand goes right through the shape. Which in fact is a window into a small room illuminated by colored lights. The magic is created by the fine wedge edge of the window, which makes it seem to disappear, and the curved walls of the room beyond, which eliminate the corners that usually help us get our bearings. Turrell is always disorienting us.

The most spectacular artwork here is one of Turrell’s ganzfeld installations, a curious room (like the one pictured above) you can walk into that feels like something out of Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film “2001: A Space Odyssey.” All details and corners that might orient us have been eliminated, except for the entrance portal, so it feels as if you’re walking into … a fog of brilliant color, cycling through blue to vermilion to magenta to overcast white, like dawn experienced from an airplane up among the clouds. The end wall seems to be cut out in a rectangular shape with round corners. Sometimes it feels like wall, sometimes it nearly disappears, sometimes it feels like a portal into another dimension.

Turrell’s spaces radiate mysterious force and power, vast and serene but also at times unsettling. They feel psychedelic and transcendental, like stunning sunsets or sacred temples or the awesomeness of the cosmos.

Jenny Holzer

“Abuse of power should come as no surprise” was one of the slogans, plastered around New York on broadsides in the late 1970s and later on scrolling electronic signs, that first brought Jenny Holzer to fame. She adapted the methods of advertising to challenge consumerism, misogyny and power.

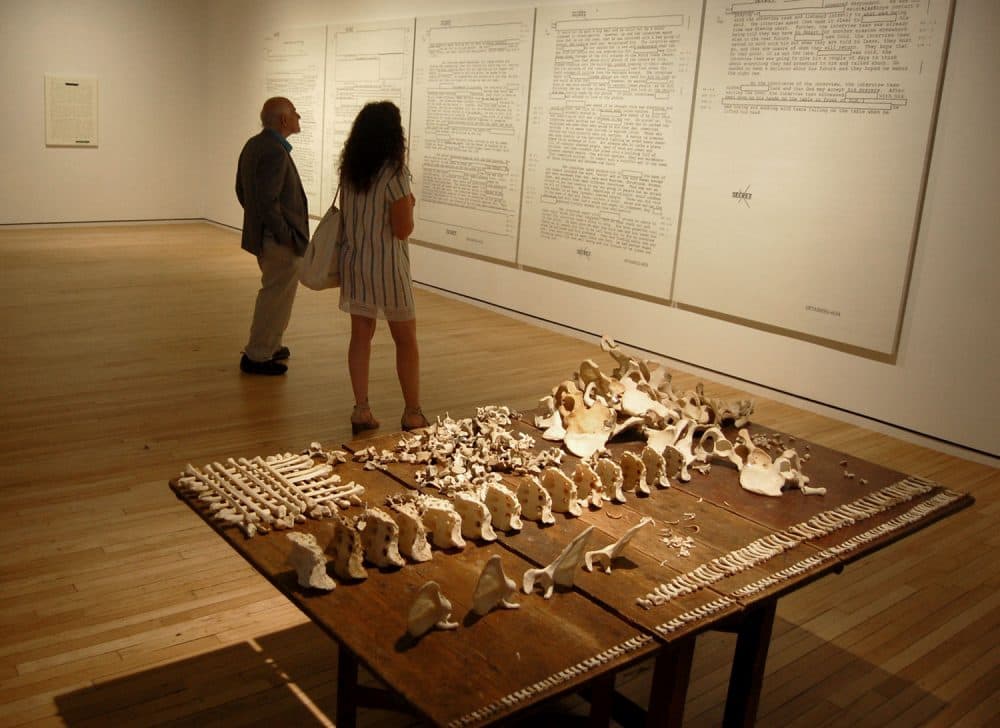

Here as part of a 15-year project, Holzer, who now splits her time between Hoosick Falls, New York, and New York City, presents tables of actual human bones tagged with metal bands that speak about sexual abuse and dozens of screenprints of declassified American military documents recording prisoner abuse in Iraq, Afghanistan and our various prisons. The corner of one gallery has a series of LED arches and then one long LED sign running along the base of the wall. Words scroll across the signs — military reports of an American soldier smashing the butt of his gun into a bound prisoner’s face and literature about hiding in the shadows as boots approach. Holzer puts us in the minds of the perpetrators and victims in artworks that are both strident and chilling.

Holzer will debut with a series of new light projections of texts scrolling across a half-mile long section of the River Street side of the complex on evenings from May 28 to June 25.

Laurie Anderson

Laurie Anderson is most famous for her 1982 album “Big Science” with its hit song “O Superman,” which reached No. 2 on the U.K. music charts and catapulted her from obscure downtown New York performance artist to brilliant, spiky-haired, MTV art-rock weirdo. In the song, her voice had an electronic filter that made her sound a bit like a cyborg and signaled her signature cross pollination of music, performance and technology (she was once an artist-in-residence at NASA).

As part of a 15-year partnership with MASS MoCA, Anderson is presenting a gallery of large drawings featuring her late rat terrier Lolabelle (also the subject of Anderson’s 2015 film documentary “Heart of a Dog”), a recording studio and listening space, and two immersive virtual reality experiences (neither available to experience at press previews last week).

“She’s essentially recreating the inside of an airliner that you’ll experience through virtual reality,” MASS MoCA's Joseph Thompson says. “And there’s Laurie’s sitting three seats up and as the plane starts to erode around you, there’s Laurie again whispering in your ear.”

“You’re left floating in space. You can grab these objects that tell you stories,” curator Denise Markonish says. “So much of Laurie’s work is about storytelling. This is another way of telling stories.”

Gunnar Schonbeck

Gunnar Schonbeck (1917-2005) grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts, playing in family orchestras in his living room. He began teaching clarinet at Smith College as a teenager and later taught at Wellesley College, Harvard and MIT. Ultimately, he educated students for 53 years at Bennington College in Vermont.

With help from colleagues and students, he invented one-of-a-kind instruments out of plywood, recycled airplane fuel tanks and old auto parts. And he led eccentric orchestras of hundreds of people, from young amateurs to experts, to play them.

“People have a notion that musical instruments must be made of certain things,” Schonbeck told People magazine in the 1982. “In fact, they usually have grown out of what’s been readily available in an environment.”

As part of a 25-year project most of Schonbeck’s instruments have come to MASS MoCA in a display that recalls school music rooms. “There’s still things in his basement and garage. This is the things that survive,” says guest curator Mark Stewart, who is part of the new music ensemble Bang on a Can and music director for Paul Simon. “Things were starting to end up in dumpsters.”

In Schonbeck’s democratic spirit, museum visitors will be free to play his instruments — deconstructed pianos, steel-string harps, gongs, tall plywood “sound towers,” metallophones, trapezoidal fiddles, a gamelan, a koto, chime racks, a vertical wooden xylophone. They seem like something a Dr. Seuss orchestra might play.

“We’re in the process of restoring the instruments so we can bring the sound out again,” Stewart says. “I think it’s going to be an experience where people immerse themselves in sound and improvisation.”

Joe Wardwell

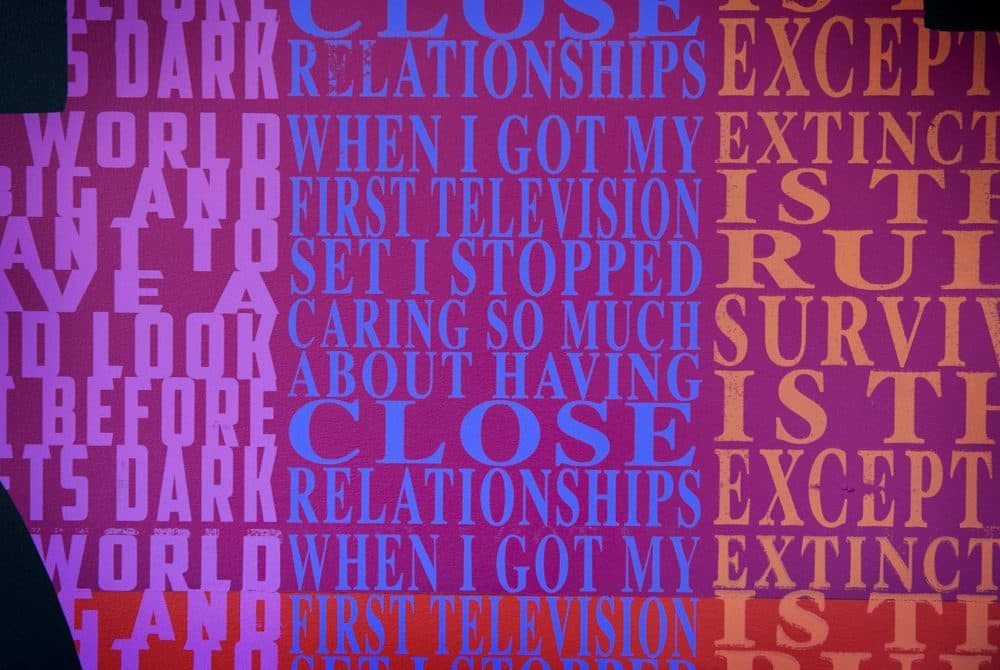

One of the first things you see when you enter Building 6 is a 140-foot-long mural in eye-popping reds, pinks and oranges by Boston artist Joe Wardwell. “Fame and fortune is a stupid game. Fame and fortune is the game I play” part of it reads in monumental letters painted over a bleak panorama of trees — based on a winter hike in the Berkshires — silhouetted against a glowing blue and yellow sky.

“I wanted it to feel like a barren landscape, a post-apocalyptic landscape,” says Wardwell, whose art often speaks about the mythology of America by mixing references to the 19th century tradition of heroic American landscape paintings with lyrics from rock 'n' roll, in this case words from the 1981 song “Fame and Fortune” by the Boston post-punk band Mission of Burma.

The mural is titled “Hello America: 40 Hits from the 50 States,” inspired by J.G. Ballard’s dystopian 1981 novel “Hello America” about an expedition across America a century after an ecological disaster. Eventually, the explorers find a mad “president,” who pledges, “Together, Wayne, you and I can make America great again.”

So Wardwell’s inspirations here include odd premonitions of the Trump presidency. “It’s the fragility of democracy, the fragility of what people take for granted,” Wardwell says. “Definitely because of the times we’re in my work has gotten more political. I’ve always been interested in patriotic ideas and challenging them and using subculture to run counter currents with that. For me, in this time, I feel it’s my responsibility to step up. Who knows if I’m going to change anything, but you don’t know. Maybe you inspire somebody. Everybody’s got to play their part.”

Wardwell painted the mural over three weeks with the help of a varying team of up to four assistants. It’s scheduled to stay on view for two years. Smaller texts are screenprinted under and between the Mission of Burma lyrics.

They include quotations from Louis Brandeis, Richard Pryor, Patti Smith, Charles Bukowski, Anne Sexton and Andy Warhol. “You move across the piece the way the character moves across the landscape,” Wardwell says, “finding bits of dislocated American culture.”

The oldest quotation might be from Abraham Lincoln: “If we falter and lose our freedoms, it will be because we destroyed ourselves.”

Spencer Finch

Finch makes paintings, lights and window glass installations that attempt to meticulously replicate the atmospheres of specific times and places — from the ceiling above Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis couch to the crisp sky near Emily Dickinson’s Amherst home. His art is often seen as a descendant of James Turrell and other Light and Space artists' work.

Since Feb. 4, the New York artist has suspended 150 three-bulb light fixtures over an 80-foot-long hall. Called “Cosmic Latte,” it’s meant to evoke the shape of the “Milky Way as it is observed in the Northern Hemisphere in March.” It has a warm, cheery glow intended to be the average beige hue of the universe.

Robert Rauschenberg

In the 1950s, Rauschenberg (1925–2008) was at the vanguard of the generation of artists figuring out the next big thing after the success of New York’s abstract expressionist painters like Jackson Pollock. Working out of New York, he became one of the titans of Western art of the second half of the 20th century by making “Combines” — assemblages of salvaged tires, signs, clocks or taxidermied birds sloshed with paint. It was art as compost, bringing the detritus of American streets right into the paintings.

He’s got two artworks on view here for about two years. The better one, “The Lurid Attack of the Monsters from the Postal News Aug. 1875 (Kabal American Zephyr),” from 1981, is a 17-foot-long rectangular wood and aluminum box balanced on a pair of small wheels at the middle. The sides are printed with photos of ships rigging, soldiers in gas masks, mice, butterflies, John Lennon playing piano, kids in a pool. Four rusty saws form a series of arches across the top. Rauschenberg’s other artwork here is a set of 11 screens printed with photos. Rauschenberg was a prolific artist, brilliant, but uneven, who at times, particularly late in his career, when he resided in Florida, could seem to be phoning it in. These are late pieces.

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) the French-born, New York-based sculptor was a master at making dreamlike sculptures of giant spiders, unsettling rooms and the realms of flesh and sex.

A shiny aluminum sculpture from 2009 hangs from the ceiling of one gallery here. From certain angles it appears to just be a jumble of chrome pipes. But then, two pairs of feet come into focus, and, at top, a pair of heads that seem stretched and blurred by motion. Around the middle, hands clutch and embrace. It’s called “The Couple,” and the tangle of limbs evokes the urgent, grasping feeling of a moment of passion.

Other sculptures here include a pair of giant eyes staring out from a hunk of rock and a block of white marble carved with tubes and folds and holes that might suggest female anatomy. You get a sense of Bourgeois’ interests, but she was a better, more striking artist than you’d guess from most of the sculptures here.

Lonnie Holley and Dawn DeDeaux

This pairing — dubbed “Thumbs Up for the Mothership” and organized by MASS MoCA curator Denise Markonish — seems to be a room of haunted ruins. It showcases two artists who’ve participated in the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation’s studio residency program in Captiva, Florida — and both have a thing for salvaged materials.

Holley, who is based in Atlanta, became known for a yard-art environment he created that filled two acres outside his Birmingham, Alabama, home with old shoes, ladders, a busted television, tires and bones. In 1997, it was destroyed, home and all, as part of a planned airport expansion.

DeDeaux is a New Orleans conceptual artist whose recent work has been inspired by a notion that the earth is on its last legs. Here she offers a Mardi Gras mask, listing columns, ladders made of charred wood or transparent acrylic, a wrecking ball suspended from an ornate ceiling mount.

Holley’s art here includes wrecked organ surrounded by a bent horn, smashed violin and other ruined instruments. He also shows a wooden stepladder wrapped with barbed wire and jumble made from old computer, a telephone and other electronics parts. At the top is a lit-up globe. A third Holley piece is a voting booth with a gun grip on the outside aimed where the voter’s head would be. It’s titled “In the Grip of Power.”

Here's a quick walk through:

This segment aired on May 28, 2017.