Advertisement

Review

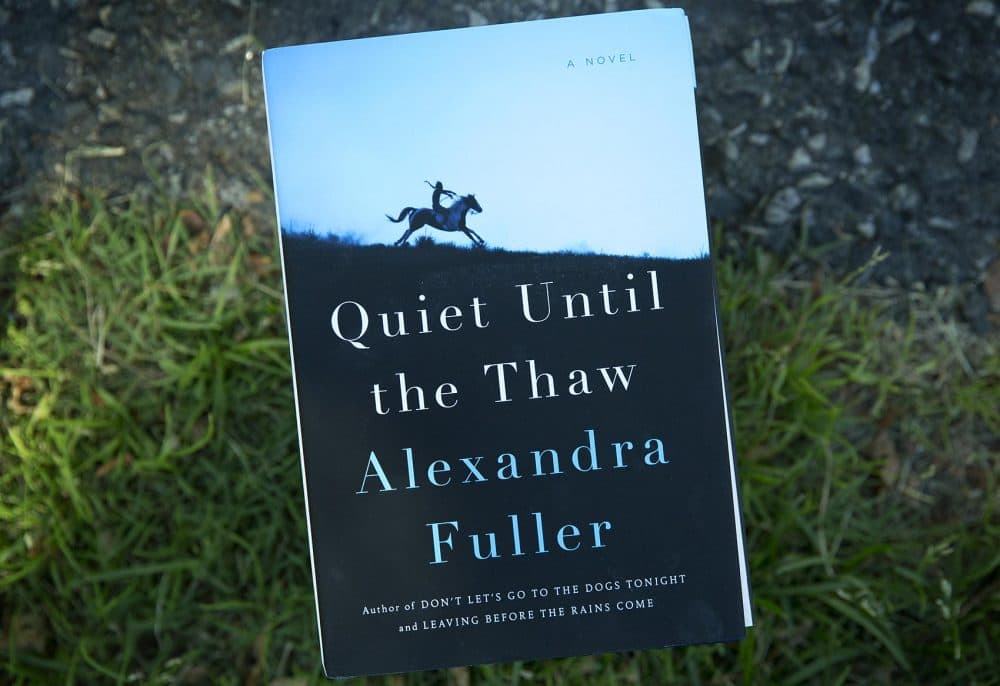

Audacious But Genuine, 'Quiet Until The Thaw' Depicts Oglala Sioux Culture With A Modern Tale

Alexandra Fuller’s first novel, “Quiet Until the Thaw,” is a fearless book. Or rather, Fuller is a courageous writer, as is evident in her three stellar memoirs, beginning with the pathbreaking “Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight.” However, for a white woman raised in southern Africa to tell the modern story of the Oglala Sioux people and the Wounded Knee uprising of 1973, a certain measure of audacity is required.

Audacious she is, but also genuine. In 2011, Fuller rode across the country with 400 Lakota Oglala Sioux to commemorate the murder of Crazy Horse, and then to her own surprise, chose to stay on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation for several months afterwards. As she explains in the introduction, “For the first time since coming to the United States in the mid-nineties, I neither needed to explain myself nor have the world explained to me. The people who live there made sense to me on a blood and bone level ... To be back among the lively dead of the Lakota, to be back among people who know Time the way I’d known it as child and a young woman was to find myself shocked into a completely unexpected homecoming, if home is where your soul can settle in recognition.”

Airy and spare, “Quiet Until the Thaw” depicts a wide swath of history through only a few evocative brush strokes.

Airy and spare, “Quiet Until the Thaw” depicts a wide swath of history through only a few evocative brush strokes. Two boys — cousins raised as brothers — are born in the middle of the 20th century on a South Dakota reservation. “Before Indian boarding school swallowed them up,” their shared grandmother, midwife Mina Overlooking Horse, suckled and fed and gruffly cared for them both. But though inseparable as children, You Choose Watson and Rick Overlooking Horse choose wildly divergent paths in life. One evades the draft, the other is severely injured in Vietnam. One becomes a drinking, drugging, corrupt tribal official, the other a solitary, incorruptible, genuine leader. As adults, their encounters are less meetings than collisions. But as old men, they each play an essential role as protectors and guides to two young boys whose lives will both mirror and illuminate their own.

In this book, and, Fuller would have us understand, in Sioux culture, history repeats itself the way a good joke is slightly altered and always surprising with each retelling. Time is a prankster who dances in a circle, never in a straight line. “There is no word for ‘good-bye’ in Lakota, only “Doksa ake waunkte.” Meaning ‘I will see you again, later,’” Fuller tells us. “Since all things are connected, always and for all time, there is no avoiding reunion.”

Interconnectedness, the inevitability of seasons and suffering (and joy) — this is the stuff that “Noble Savage” tropes are made from. But with trenchant wit and appropriate rage, Fuller dodges cliché. Just listen to this account of the suffering of You Choose What Son (who has changed his surname from Watson) after he has committed a despicable act. “Grief is an eroding wind. After grief has blown through, there is just the bedrock of a person ... in the perennial boot camp of suffering also known as the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, also known as the Rez, also known as Prisoner of War Camp #334, even a certified idiot knows the only pain a person can avoid is the pain that comes from trying to avoid pain.”

...“Quiet Until the Thaw” is not so much a conventional narrative as a progression of vignettes, less a tale to be read than a chronicle to be heard.

I say listen, because “Quiet Until the Thaw” is not so much a conventional narrative as a progression of vignettes, less a tale to be read than a chronicle to be heard. The voice of the storyteller, Fuller’s voice — by turns acerbic, compassionate and wry — imprints us almost more than the story she tells. And her gaze, though narrowly focused on a handful of Oglala Sioux characters, illuminates much more than their lives. Beyond spanning relatively large swaths of time, the book covers many physical territories as well — from the Rez in South Dakota to Vietnam, from Paris Disneyland to the moon. And in these snippets of cultural conquest, it is as much a history of (white) American capitalism in the 20th century as of a people oppressed by it.

Some will legitimately argue that as well-intentioned Fuller may be, it would be far more meaningful for publishers to issue more books by Native American writers about Native American lives. I agree with them ... but not at the cost of minimizing the value of this singular novel. In a very brief chapter titled “One Common Myth About the Rez, Dispelled,” Fuller writes:

The Rez is not a complicated place; it is an essential place.

Essential. Meaning, there is nothing more that can be taken away, removed, or forgotten.

Essential. Meaning, there remains only what is absolutely necessary.

Essential. Meaning, it doesn’t get any more real than this.

“Quiet Until the Thaw” should not be a proxy for novels by indigenous people, but will, I hope, serve to prompt and build commercial demand for them. Meanwhile, it’s an essential book.

Alexandra Fuller will be reading from "Quiet Until the Thaw" at the Harvard Book Store in Cambridge on July 10 at 7 p.m.