Advertisement

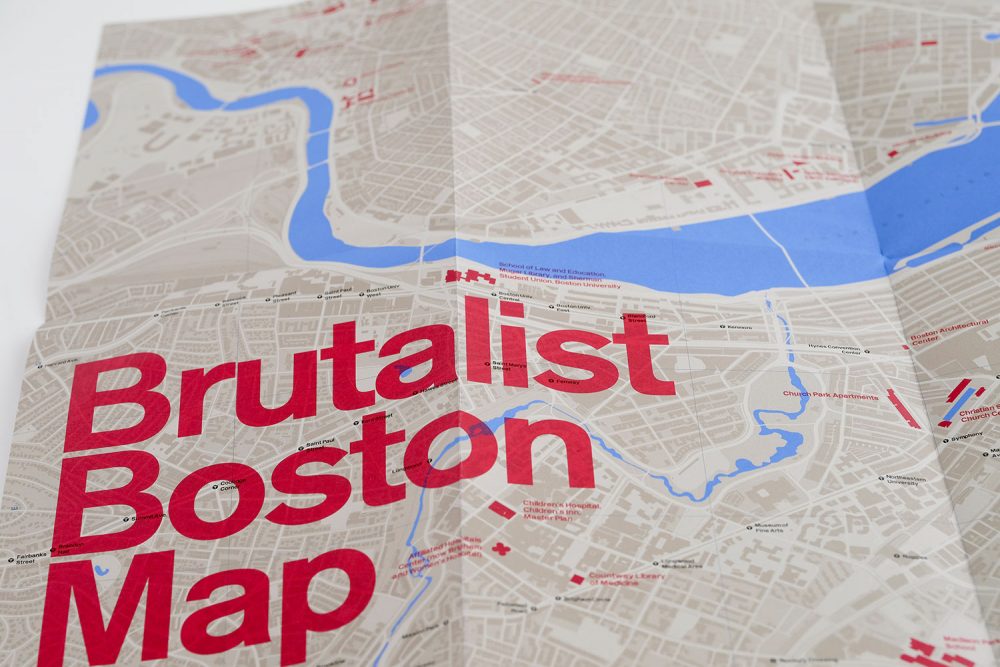

Brutalism Is Back? A New Map To Boston’s Monumental Concrete Architecture

It seems like no one can be impartial when it comes to brutalism — the mid-20th century monumental concrete architecture — in Boston.

The buildings remain controversial because they are seen as impersonal and too often tied up with federally-backed urban renewal projects that fractured some neighborhoods and decimated others. Like Boston’s West End, razed to create Government Center, which became home to Boston City Hall. That half-century-old building has been vilified as one of "The World's Top 10 Ugliest Buildings and Monuments" by the, um, experts at VirtualTourist, but also, in June, called one of “The 10 Most Beautiful City Halls in the U.S.” by the architecture and design publication Curbed.

“I think a lot of people locally conceive of this as a moment of blight in Boston, whereas the map positions it as the moment deserving of international recognition in terms of the broader [architectural] work that we have in our city,” says Mark Pasnik, who along with colleagues Chris Grimley and Michael Kubo has authored a new “Brutalist Boston Map,” published by London’s Blue Crow Media. The trio literally wrote the book on brutalism in Boston — their 2015 history “Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston,” which won a 2017 “advocacy award of excellence” from the architectural preservation group Docomomo US and a 2017 “preservation achievement award” from the Boston Preservation Alliance.

“Mapping these buildings reveals a deep pattern of reinvention in one of the nation’s oldest cities, recording a time when architects embraced the future wholeheartedly,” they write in the introduction to the map. It’s available through the publisher (Blue Crow Media) and at online mega stores; plus they’re aiming to have it available in local shops soon. Or you can acquire copies at the launch party and one-night exhibition on Tuesday, Aug. 1, from 6 to 9 p.m., at the Boston architecture and design firm over,under’s pinkcomma gallery, 46 Waltham St., which the three men curate.

The map, which highlights 48 buildings, and book show how concrete architecture — from City Hall to schools, hospitals and housing — transformed the city in the 1960s and ‘70s as part of a concerted effort by community leaders to reenergize the area and signal a reformed political leadership.

“It was a remarkably concentrated moment of the city’s evolution. It’s really about 15 years of coherent production of these buildings,” Grimley says.

For proponents, this monumental concrete modernist architecture was seen as symbolic of a new, robust culture rising from the ruins of the Great Depression and World War II, of the power and daring of big government, of a new civic spirit to improve lives. Highlighting the construction materials and their structural strength was heralded as a form of honesty. The term brutalism derives (at least in part) from the French “béton brut,” meaning raw concrete, but carries connotations of “brutal,” which is how many unfavorably view the structures.

“I get a sense that brutalist will swing back around,” Pasnik says.

In fact, last fall, a New York Times headline announced “Brutalism Is Back” and the Guardian published an essay titled “Concrete Jungle: Why Brutalist Architecture Is Back In Style.”

“It’s fairly zeitgeisty,” Grimley says. “If you look at the number of books on brutalism in the last four or five years, there’s a fairly decent stack of them.”

Pasnik says the map — illustrated with photos of many of the buildings — is “an entry point that’s meant to get you to go out to look at the buildings.” It’s part of Blue Crow Media’s series of city maps of brutalist architecture in London, Washington, D.C., Paris and Sydney. “We asked to call it ‘heroic,’ but brutalist is the brand,” Grimley notes.

“It has some power because it places Boston as a main international center of this work. Our position is that Boston is the premiere U.S. city for this,” Pasnik says. “Washington has as many or more buildings, but not necessarily as high quality or as high a level of designer. Boston having the only building in North America by Corbusier puts it in the elite.”

“If you were to look at who was working in Boston in the early ‘70s, it was really the who’s who of architecture,” Grimley says. In addition to Le Corbusier’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University (built 1961 to ’63), Boston and Cambridge offer buildings by I.M. Pei, Paul Rudolph and Marcel Breuer, in additional to locally grown firms like The Architects Collaborative. "Ed Logue" — the powerful leader of the Boston Redevelopment Authority (now called the BPDA) during the period — "really sparked the reinvention of the city,” Grimley says.

The map highlights landmarks, like I.M. Pei and Partners’ Christian Science Church Center (built 1968 to ’73), as well as “hidden gems” like Eduardo Catalano’s Charles River Park Synagogue and Charlestown Branch Library, both built in 1970; F.A. Stahl’s 1968 building at 70 Federal St.; and Marcel Breuer and Tician Papachristou’s Madison Park High School, built 1974 to ’78. The map also reveals clusters of brutalist buildings around Boston City Hall and Harvard Square in Cambridge.

Pasnik, Grimley and Kubo have been working to get people to reconsider brutalist architecture here with exhibitions and talks and publications for about a decade now. The Walsh administration’s endeavors to spruce up Boston City Hall and its surrounding plaza a bit — including restoring lighting and commissioning a master plan to upgrade the building — can be seen as one of the results.

“It’s been taken much more seriously by this administration that it’s a building that can be improved than by any administration since it was built,” Pasnik says.

“I think the needle’s moved. It’s two steps forward, one step back,” Grimley says. “There’s a lot of press that’s come out and used the term [heroic] or talked about the work in ways that are much more productive.”