Advertisement

As The Opium Trade Boomed In The 1800s, Boston Doctors Raised Addiction Concerns

ResumePart 2 of a two-part story. Here's Part 1.

In the early 1800s, many Boston merchants became millionaires in part by selling opium illegally in China. The profits funded Boston-area schools, libraries, hospitals and early ventures into the industrial revolution, creating a financial dependence on the opium trade.

The opium trade fueled an epidemic in China — and there are signs the merchants unwittingly fed addiction in Massachusetts.

Take this editorial in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (BMSJ), forerunner of the New England Journal of Medicine. It was published in 1833, during the peak period when Boston merchants were sailing to Turkey to buy opium, stopping in China to sell the drug, then returning home with tea, silk, porcelain and some opium.

The editorial from Sept. 4, 1833, begins with this question:

Is there any sure and safe method of curing a person of the habit of opium [use], when that habit is confirmed by many years' of use of the article?

The author, a doctor, says he asks the question on behalf of a young woman who was prescribed opium to treat "a slight nervous irritation." She's become "a bound and servile slave" to the drug, and alarmed to realize she must increase her dose to avoid feeling sick. For almost a year, the doctor has tried everything he can think of, including substituting other drugs and attempting to wean the patient off opium. But she, "whilst under a course of gradual reduction or of substitution, convulsed for hour after hour in every muscle, and vomiting almost with intermission."

Physicians today would recognize these as common symptoms of detox or withdrawal. And it appears doctors in 1833 were becoming familiar with this stage of opium addiction as well. Comments about the "opium habit" and suggestions about how to treat the woman poured in to the journal offices in Boston, above what is now the Downtown Crossing MBTA station.

"Starting with the next issue, you see a flood of doctors saying, 'Hey, I also know people that are addicted to opium. Here’s what I’ve done to treat them and this is actually a bigger problem than we realize,' " says Jonathan Jones, a Ph.D. history candidate at Binghamton University.

The First Addiction Warnings

The conversation triggered by the 1833 editorial is astonishingly similar to those taking place in hospitals, pharmacies and doctor's offices today. Most doctors who wrote in to the BSMJ divided patients into two categories: those who became addicted as a result of a physician's prescription, and those who took opium without consulting a doctor, perhaps just for fun.

Those early 19th century doctors argue they are obligated to help patients who get hooked on a medicine, but not those seeking a thrill. Jones says some doctors dismissed patients who were too poor to see a doctor, especially women and immigrants, and purchased opium directly from a pharmacist.

"They were not worthy of doctors intervening and trying to help them," says Jones, whose work explores the way physicians defined the "right and wrong" kinds of addiction patients.

A month into the conversation, back in 1833, a physician from Northampton, Dr. C.L. Seeger, raises an issue that is still controversial in some circles: Is opium addiction an illness or the sign of a weak, immoral character?

"I consider this practice generally a real and complicated disease," writes Seeger, who says he's certain he can "prove the correctness of the definition just given, at least to every unbiased mind."

Thus began the first robust warnings about opium addiction in Massachusetts. The conversation revealed a problem: Physicians and pharmacists were dispensing opium without regard for its potentially dangerous effects.

"Most of this would be what we would think of now as prescription drug abuse," says Elizabeth Kelly Gray, associate history professor at Towson University.

Opium was becoming one of, if not the most common medicine of the time.

"The tendency was to keep laudanum [a liquid form of the drug] on hand the way we keep Tylenol today," Gray says.

There were no limits on the drug's use and no restrictions on who could purchase it. Twelve-year-olds might stop at a druggist to pick up a bottle for their mother. In a typical case of addiction, a patient would start taking laudanum or opium pills to treat a headache, insomnia, diarrhea, stomach pains, cholera or a toothache, "and then three years later the person is still using it," Gray says.

Historians do not have records that connect patients who were becoming addicted directly to opium unloaded on Boston wharves. But the traders returning from China are a likely source of the drug.

"They do bring home small supplies of opium, usually what they can’t sell in China," says Sam Houston State University historian Thomas Cox.

In diaries, opium merchants mention taking it themselves.

"They just simply refer to it as the drug or the blue pills," Cox says. "Opium was compressed into these small pills, which you could make in a chemist’s shop very easily."

It's not clear how much opium was coming into Boston in the early 1830s, when doctors sound the alarm.

"It was enough to keep a medicinal trade going," says Jonathan Goldstein, a research associate at Harvard University’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies.

David Courtwright, author of "Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America," estimates the annual total for all U.S. ports was just over 27,000 pounds a year between 1827 and 1842. Boston merchants were the dominant American opium traders.

'Opium Habit ... Prevalent In Many Parts Of The State'

The conversation about opium addiction continues in the BMSJ through the 1830s and into the next decade. Many writers warn about accidental overdoses. One writer argues that a mother or her apothecary should be held responsible for the death of a 3-month-old infant given drops of an alcohol-based opium medicine.

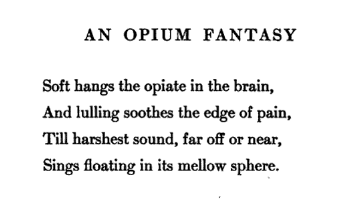

Poems about opium use appear in Boston literary journals, including Maria White Lowell's "An Opium Fantasy" and Rose Terry Cooke's "Poppies."

Opium addiction does not reach epidemic proportions in the U.S. until the late 1800s. It was a legacy of the Civil War, when the opium derivative morphine was widely distributed to both Confederate and Union soldiers. But Courtwright says the real driver was the introduction of hypodermic needles, which delivered strong doses of morphine that produced immediate relief and were overused.

Massachusetts would not be particularly hard hit during this opium epidemic, but as it builds, state public health officials worry. Doctors and pharmacists report that opium consumption is increasing every year and urge the state to prepare for this insidious foe.

Dr. Fitch Edward Oliver, a physician at what was then Boston City Hospital, distributes a questionnaire to physicians and druggists across Massachusetts. He compiles the results in an essay called "The Use and Abuse of Opium," which is included in the state's third annual health report, published in 1872. Some communities say they do not have anyone addicted to opium, but Oliver concludes that "the opium habit is more or less prevalent in many parts of the state."

In Boston, he says "two prominent druggists each have six habitual users" and "in parts of the city where those addicted to the habit mostly reside, the sales are much larger." In Worcester, "one druggist reports that opium is used to an alarming extent." And in Chicopee, in western Massachusetts, "the druggists report a great many regular customers."

Oliver says women, particularly those in rural areas, appear to be at greatest risk, which he blames more on moral than physical causes.

"Doomed, often, to a life of disappointment, and, it may be, of physical and mental inaction, and in the smaller and more remote towns…deprived of all wholesome social diversion, it is not strange that nervous depression, with all its concomitant evils, should sometimes follow,-opium being discreetly selected as the safest and most agreeable remedy,” Oliver writes.

It was a change in prescribing behavior that brought the post-Civil War opium epidemic to an end.

Oliver suggests that opium addiction may be on the rise in reaction to the prohibition of alcohol. A temperance movement that lead to a ban on the sale and manufacturing of alcohol in Maine in 1851 was spreading across the country. But the Massachusetts Board of Health says nothing in Oliver's paper proves "that any clear connection exists between this evil and a legally enforced abstinence from the use of alcoholic stimulant."

Again, as in 1833, doctors responding to questions about addiction in 1872 say, according to Oliver, it is "caused by the injudicious and often unnecessary prescription of opium."

Historians say it was a change in prescribing behavior that brought the post-Civil War epidemic to an end.

"Doctors became much more circumspect about prescribing," says Courtwright, who teaches history at the University of North Florida. "Even before the federal government intervened with the 1914 Harrison Narcotic Act, the medical profession was becoming much more cautious about prescribing opiates."

Courtwright says he’s been surprised to see another opium epidemic, driven by over-prescribing, emerge in the U.S. — and disturbed because this one is more complicated.

"One thing a morphine addict in 1890 didn’t have was a massive alternative supply of something like heroin," says Courtwright. "Now increasingly that cheap heroin is spiked with cheap and potent synthetics, like fentanyl."

Most of that fentanyl or the ingredients used to make it are produced in China and shipped to the U.S.

"In the 19th century, China was widely seen as a drug consumer nation. Now, in the early 21st century, it is a producer nation, especially when it comes to drugs like fentanyl," Courtwright says. "There is a kind of bitter irony in that."

Share your experiences, and follow along with our reporters as they cover opioid use and treatment, by joining our Facebook group, "Living The Opioid Epidemic."

This segment aired on August 1, 2017.