Advertisement

Can Geometry Help Fix Our Political System? Mathematicians Invite Public To Fight Gerrymandering

Resume

A group of Boston-based mathematicians calling themselves the Metric Geometry and Gerrymandering Group are using their math superpowers to fight back against gerrymandering.

They're holding a public event, the Geometry of Redistricting workshop, which begins on Monday. The workshop will feature lectures on legal and mathematical topics related to gerrymandering, as well as hands-on sessions on how to use open-source mapping software to redraw voting districts.

The connection between math and gerrymandering may not be obvious at first, but gerrymandering is (in part) about manipulating the shapes of voting districts -- and who knows more about shapes than geometry experts?

The geometry and gerrymandering group was founded by Tufts mathematician Moon Duchin, when she realized that her work had real-world applications to gerrymandering.

Mira Bernstein is one of the four core members of the group -- all mathematicians and computer scientists at local universities. She says that when she and her colleagues announced earlier this year that they'd be holding a public workshop on the geometry of voting districts, they did not expect a big response.

"When we sent out the original email about this to just a bunch of our friends we thought, 'Oh, we'll get 30 people together and they'll talk math and it'll be a small gathering,' " she recalls. "And then we got just thousands of responses right away."

Bernstein says their mailing list ballooned to 3,000 people within a month, and they got more than a thousand applications to attend their specialized training tracks, which will take place after the initial three-day public workshop.

The organizers' aim is to get the "mathematically inclined" more engaged with issues surrounding redistricting. So far, they seem to be succeeding: more than 500 people from 40 states as well as overseas have signed up to attend the workshop portion of next week's event.

Bernstein says that a lot of the people coming to the conference are mathematicians, but a lot of them aren't. "They're people in quantitative fields, computer science, just generally quantitatively educated people who want to see how they can bring those skills to bear."

Gerrymandering — the term originated in Massachusetts in 1812 — is the dark art of drawing voting districts in such a way as to give an unfair advantage to one political party over another.

It can be achieved by a variety of methods, notably "packing" and "cracking." To dilute (or crack) a group's voting strength, for instance, you might take a community and divide it in half, putting each of those halves into districts that are dominated by other groups. Packing is when you cram many like-minded voters into the same district, so that they win that district by a larger margin than necessary. The many votes that helped them win could have been used in other districts.

Bernstein and her colleagues believe that technology is helping to make gerrymandering worse.

"In the past, both parties gerrymandered somewhat — it sort of canceled out to some extent," she says. "But now, with the kinds of data that we have, not just very precise electoral data, but also, there are organizations, both on the left and on the right, that collect internet data on people and make these very, very detailed models. So basically for almost every voter they have a model for how that person will vote.

"And not only for how they will vote," she adds, "but for where they might move and how their votes might change based on age and that kind of thing. So now, when people gerrymander, they take all of that into account. And so the gerrymanders of the last decade have actually held and been more persistent than the gerrymanders of previous decades."

Lawrence Lessig, a Harvard law professor and outspoken critic of our current districting system, agrees that technology has made things worse.

"What's really important about this process is that big data, technology, has radically improved the efficiency by which the politicians are now able to draw and select these districts."

Lawrence Lessig, Harvard law professor

"What's really important about this process is that big data, technology, has radically improved the efficiency by which the politicians are now able to draw and select these districts," he says. "That change has had enormous consequences in just the last redistricting cycle, when Republicans were much more advanced in the deployment of that technology, and succeeded in districting the nation so that it's really almost impossible for the Democrats to regain control of the House."

Lessig points out that gerrymandering is done by both Republicans and Democrats.

"I think at the grassroots level, this should not be, and really is not, partisan," he says. "I think if you ask ordinary voters about any system designed to disable the ability of people to have their voices represented, they would be frustrated by that. And if in places like Massachusetts you said to Republicans, 'Look, you are systematically unrepresented because of the way districts are drawn,' they should be as furious with that as any Democrats in Ohio would for [playing] the same game."

Bernstein and her colleagues are quick to say that they are non-partisan, and simply want to help end unfair redistricting processes. They're focusing in part on the legal notion of "compactness," which is sometimes used in courts as a way to detect gerrymanders.

Bernstein says that her collaborator Moon Duchin realized while teaching a course for undergraduates that some of her research and geometry might apply to the problem of figuring out whether congressional or legislative districts are "compact".

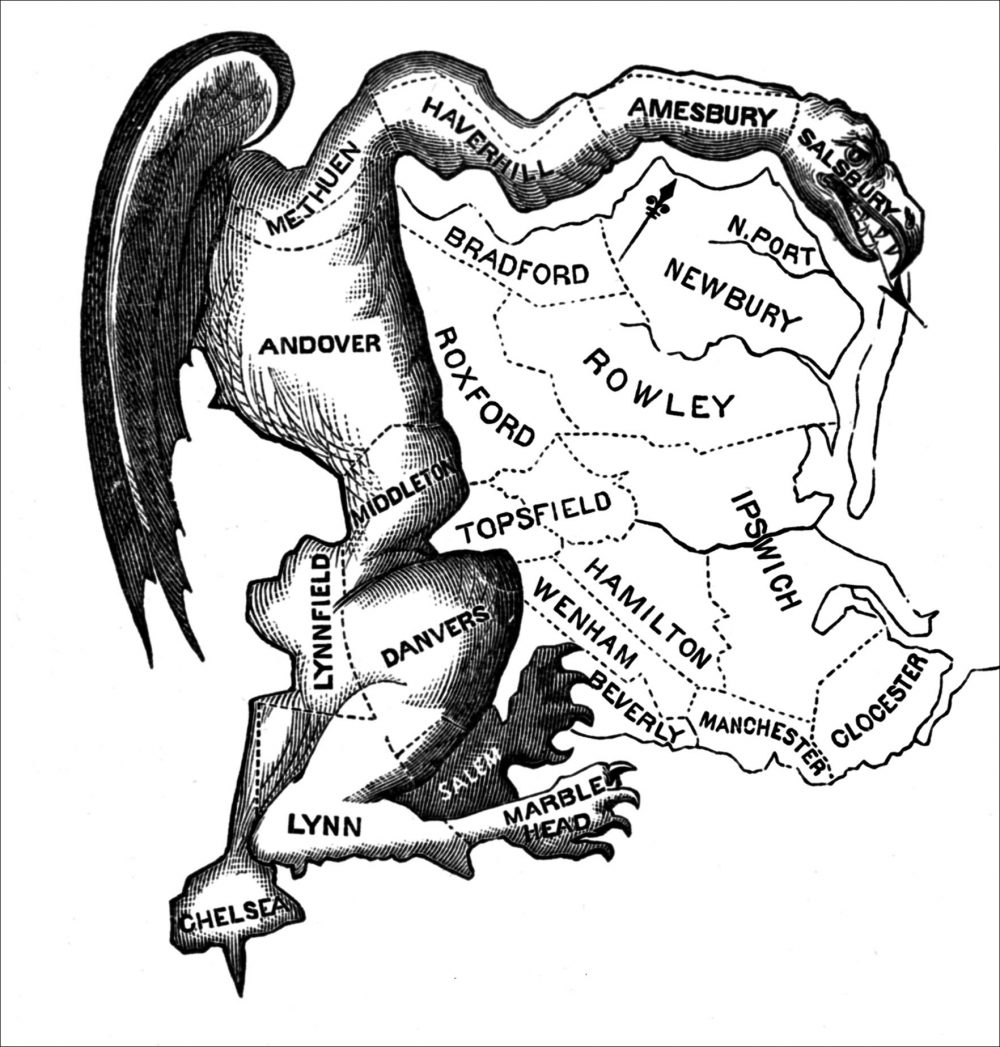

"Most states require their legislative districts to be compact without specifying exactly what that means," Bernstein says. "And most people have an intuitive idea that compact means some kind of nice shape, maybe a circle, maybe a square, not something that looks like an octopus." (And not like the eponymous Gerry-mander depicted in the 1812 political cartoon below, which was named after Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry when he signed a bill that allowed districts to be redrawn in his party's favor.)

The mathematicians believe that they and other numerate people may be able to help better define "compactness." But beyond that, they want to be part of the public conversation about gerrymandering — hence next week's public workshop, as well as four more to be held across the country in coming months.

And in the run-up to the next census in 2020, which will trigger redistricting throughout the country, mathematician Bernstein says they're also trying to build a community of people with quantitative skills who are interested in the problem of gerrymandering.

"People who understand the basics, who've thought about it and who can get involved in various ways in 2020 and 2021," she says. "And I think that that is going to be our main contribution, perhaps, just getting people involved."

This segment aired on August 9, 2017.