Advertisement

Edith Wharton’s Enduring Insights On Women, Food And Weight

If only I’d appreciated Edith Wharton’s keen commentary on women, food and weight, I might have saved my younger self a ton of time, effort and angst trying to diet down to an unsustainable size.

What? You didn’t know the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist was denouncing women’s quest for thin lifestyles before Roxane Gay and Sarai Walker were even born? That the early 20th-century writer not only depicted America’s newly advancing weight obsession, but was a witting observer of our national obsession as it unfolded during her four-decade writing career?

Neither did I, and I’m a psychotherapist specializing in food and body-image issues. In fact, if I hadn’t stumbled upon an obscure journal article, “Shaping Modern Bodies: Edith Wharton on Weight, Dieting and Visual Media,” I may never have appreciated Wharton’s spot-on insights into the zealous trend for dieting and the perfect body that are as relevant today as they were a century ago.

That singularly brilliant article inspired a long overdue reunion with the life and work of this literary heroine. After reacquainting myself with Wharton’s novels and acquainting myself with several biographies, my revelatory reunion culminated in illuminating interviews with Wharton scholars, a food-related tour of Wharton’s Berkshire estate; a spectacular stay at another Gilded-Age mansion and a delightful matinee of two new-to-me Wharton comedies.

Rather than pen another obscure journal article or post a required reading list, I’ve penned a quick read on Wharton’s enduring insights on women, food and weight. If you’ve ever wondered why women, and some men, end up starving their bodies instead of feeding their hungry souls, read on!

Thin Is In

According to Terry Newman, fashion journalist and author of “Legendary Authors and the Clothes They Wore,” Wharton and her characters mirrored the shifting fashions and body ideals from the late 19th century, when an upper-class woman needed to be laced into a dress by her maid, to the early 20th century, when women and their dress became more liberated.

“To be fat was to be ugly,” Newman explained in a recent email exchange. “Whether you could afford couture or not, the new, modern message during Wharton’s time was the same: thin was in. Ironically, although the disappearance of heavier duty corsets signified a progression for women’s sartorial liberation, it actually meant that a woman had to be naturally slim or lose weight to be ‘in-fashion.’”

"Excessive slimness was the fashion, and she shuddered at the thought that she might someday deviate from the perpendicular."

Edith Wharton

Women became obsessed with weight and the surest way to lose it, including the fad diets and diet pills advertised in women’s magazines. Wharton was right in the thick of it, chronicling the unprecedented dieting craze in “The Custom of the Country” and other novels.

“Only one fact disturbed her,” writes Wharton about the novel’s protagonist Undine Spragg, “there was a hint of too much fullness in the curves of her neck and in the spring of her hips.... Excessive slimness was the fashion, and she shuddered at the thought that she might someday deviate from the perpendicular.”

You Can Never Be Too Thin

Actually, the young Wharton considered herself unfashionably thin, and worked hard to gain weight. While the literary fashionista joked that she might pass for the “Thin Lady” in Barnum’s circus, she was none too pleased with her 20-inch corseted waist.

“Being underweight,” writes Laura Rattray, editor of “Edith Wharton in Context,” “was evidently a concern throughout the writer’s [life]. From the age of seventeen there are delighted notes of her weight gain,” from 123 to a high of 128.

"Being underweight was evidently a concern throughout the writer’s [life]."

Laura Rattray

As Wharton’s figure broadened with age, the weightier writer ordered customized clothes to flatten her figure until the ‘20s and ‘30s, when she wore looser fitting, column-like outfits that made corsets practically unnecessary.

Unlike the novelist, Wharton’s heroines were classically tall and slender, but never too thin, except for one: Lily Bart. In the face of financial and social ruin, “The House of Mirth” tragic heroine takes control of the one thing within every woman’s control: her diet. While starvation doesn’t cause the aging beauty’s death, her subsistence diet of tea and sleeping drugs surely weakened her resolve to keep going.

Dieter Beware

Wharton may have adhered to what’s now called the “Corset Diet” by dieters who don corsets to lose weight, but she was skeptical of fad diets, and expressed that skepticism in her memoir “A Backward Glance”:

“For years, he [her friend Henry James] had suffered from the evil effects of a dangerous dietary system called ‘Fletcherizing,’ [which called for chewing every bite up to 500 times]. The system resulted in intestinal atrophy, and when a doctor at least persuaded him to return to a normal way of eating, he could no longer digest and his nervous system had been undermined by years of malnutrition.”

And yet, Wharton wasn’t immune to the allure of fad diets.

According to a June 1899 letter published in Irene Goldman-Price’s book “My Dear Governess: The Letters of Edith Wharton to Anna Bahlmann,” Wharton reports that when she showed her doctor “a table of the diet I have been following, he folded it up, and put it in an envelope which he sealed and handed to me, saying: ‘Don’t look at that again and eat everything.’”

On doctor’s orders, Wharton did what most dieters do post-diet — she started “eating wildly right and left.”

A Woman Should Never Be Seen Eating

Wharton enjoyed good food, even overate on occasion, but she was also self-conscious and extended her self-consciousness to her heroines at the dinner table and beyond. In her writing, she depicted women eating with abandon much like People magazine does in photos of female celebs chowing down: inappropriate and unattractive.

According to Margaret Toth, an associate English professor at Manhattan College and author of the aforementioned journal article, “In terms of actual eating, Wharton’s social environment divided along strict gender lines. Male characters consume freely and often — and guiltlessly display the effects of eating on their bodies, while women eat at the risk of social ostracism. Indeed, in the novel ['House of Mirth'], Wharton seems ‘bent on exposing the absurd dictum that a woman should never be seen eating.’ ”

As I surveyed the formal dining room at Wheatleigh, my Whartonian weekend home, I was heartened to see women eating with as much gusto as men. Chef Jeffrey Thompson made it easy with his exquisite tapas-sized entrees, but still, today’s woman has greater freedom to satisfy her appetite than Wharton ever did.

Advertisement

Feed The Hungry Soul

While Wharton never suggests women “let themselves go,” she does pose an important question: When keeping up appearances takes precedence over nourishing the soul, then what? That is the question at the heart of one of “The Wharton Comedies” that Shakespeare & Company staged this summer in Lenox.

On the threshold of the afterlife, the protagonist of “The Fullness of Life” reflects on her own unfulfilled life and that of womankind: “The soul sits alone and waits for footsteps that never come.”

"[Wharton] is seemingly unable or unwilling to imagine a way for her modern female characters to escape the body dictates that dominate their lives."

Margaret Toth

In her 75 years, did Wharton come to know the fullness of life? Hard to say, but according to Toth, she “is seemingly unable or unwilling to imagine a way for her modern female characters to escape the body dictates that dominate their lives.”

Unlike her characters, counters Emily Orlando, associate professor of English at Fairfield University and immediate past president of the Wharton Society, Wharton lived a remarkably long and fulfilled life.

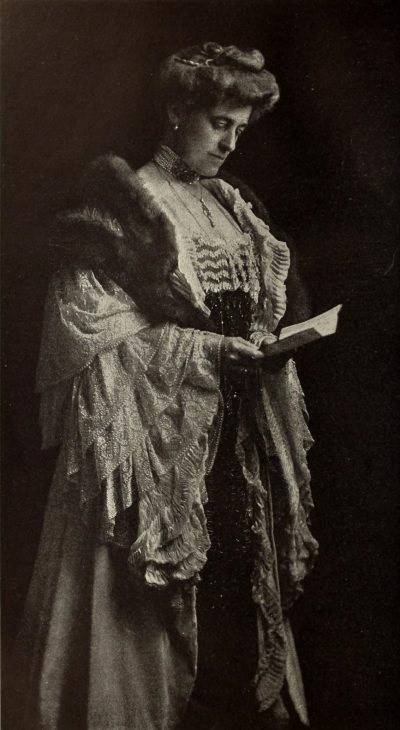

“Yes, she made an unfortunate marriage that ended in divorce,” she explains. “But if one studies the photographs of Wharton through the years, one witnesses her transformation into a woman at peace with herself, her many friends, her garden, her dogs, her homes, her international travels, her life.”

Or as the oft-quoted Wharton might say: She set the window wide and let herself drink the day.

Jean Fain is a Harvard Medical School-affiliated therapist and the author of “The Self-Compassion Diet.”