Advertisement

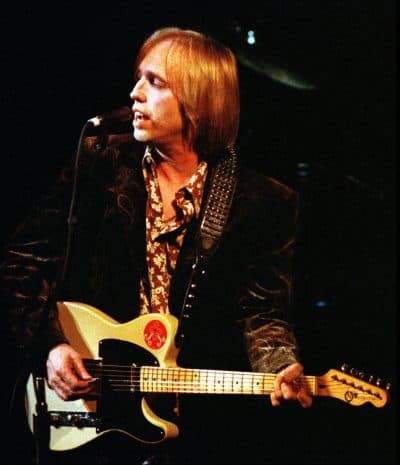

Tom Petty, The Rocker Who Wouldn't Back Down, Dies At 66

If you know his music, you know one thing that was essential to Tom Petty was perseverance.

“You can stand me up at the gates of hell, but I won’t back down,” he sang in “I Won’t Back Down.” And on Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers' final album, 2014’s “Hypnotic Eye,” he sang, “I got a dream, I’m gonna fight ’til I get it right.”

That dream died Monday.

TMZ broke the news that Petty, 66, suffered a full cardiac arrest and was found unconscious and not breathing in his Malibu home Sunday night. His wife, Dana York, called 911 at 10:45 p.m., LA time. He was taken to UCLA Santa Monica Hospital and put on life support; there was no brain activity and he was then taken off life support. CBS, Rolling Stone and other outlets reported his death later Monday afternoon, then retracted it. Petty’s death was confirmed around midnight by his longtime manager Tony Dimitriades.

“On behalf of the Tom Petty family,” said Dimitriades, in a statement, “we are devastated to announce the untimely death of our father, husband, brother, leader and friend Tom Petty. … He died peacefully at 8:40 p.m. PT surrounded by family, his bandmates and friends.”

It was a week after the band finished its 40th anniversary tour.

The first time I saw Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, they were opening a short leg of a tour for the J. Geils Band and played my local arena, the Bangor (Maine) Auditorium, in the summer of 1978. (When Petty and the Heartbreakers played the TD Garden this summer, they had Geils singer Peter Wolf and his band the Midnight Travelers open for them.)

I met with Petty back at the Holiday Inn after the ‘78 set and he told me a bit about his life for a story I wrote in the Bangor Daily News. Petty, then 26, was obsessed with rock ‘n’ roll. It wasn’t the glamour; it was his lifeblood. He started playing in Florida when he was 15 as part of the band Mudcrutch and moved to California at 21. "If I'm going to starve," he said, "there's no reason to go somewhere cold."

But Petty didn't starve. He signed a contract with Shelter Records as a solo artist in 1976. But, Petty told me, "I didn't like the sound of the session musicians. Didn't excite me very much, I just work better in a band.” Petty ran into some of old Mudcrutch buddies — guitarist Mike Campbell and keyboardist Benmont Tench — and added a rhythm section of bassist Ron Blair and drummer Stan Lynch: “We played together and made up our minds [becoming the Heartbreakers]."

They started recording two days after forming the band; Petty equated it with falling into a pool. That album, which came out in 1976, was under-promoted by ABC (Shelter's distributor), and languished until ABC changed managerial direction.

There was a triumphant three-month British tour, where they headlined over Nils Lofgren, and were seen by some as part of the emergent punk/new wave movement. They weren’t, really, and some of the punks were angry, thinking they’d usurped the name of Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers. In 1978 ABC's new promotional thrust brought the Heartbreakers to national attention. “Breakdown” and “American Girl” became hits.

When he played Fenway Park in 2014, Petty declared Boston his favorite city, and while that’s a common rock star ploy, Petty probably meant it, supplying this detail: If the now-defunct WBCN-FM hadn’t played “American Girl” in 1978 when everybody else thought the young band was dead in the water — well, he suggested, none of this would have taken place. The song caught on nationally after WBCN took the plunge. Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers went on to sell more than 80 million albums and to carve out their spot in the firmament of American rock ‘n’ roll stardom.

The Petty I met in 1978 did not exude "rock star," but had an unassuming, quietly charismatic personality. On stage he was both tender and tough; most of his songs were about the girl entanglements of which life is made. And though Petty often sang of hurt and rejection, the buoyant, melodic texture and flow led the listener away from bitterness into a belief that, "Hey, everything's gonna be all right."

I accused Petty of almost deviously devising “I Need to Know,” the first single off their second album “You’re Gonna Get It!,” for AM radio mega-success. It was so damn catchy that it cried out to be spun six times a day at any self-respecting AM rocker.

Petty hedged a bit and laughed. "I didn't really think about that, but when I heard it, I knew it might be a hit single. To tell you the truth, my visions of 'I Need to Know' and the AM radio are not very positive. I'd love to hear the radio just rock a little bit. I think that it's such a blast to come on after [Elton] John and Olivia [Newton-John]. It could really knock grandpa out of his rocking chair. I think it’d be great if [AM radio] would play it… and some of them are, bless their hearts." Turns out, Petty’s initial thought about the song and AM radio was right: The song only made it to No. 41 on the Billboard chart.

He told me about resisting record company pressure to change a key line in “Listen to Her Heart,” the second single from the album. Petty sang about a rich, romantic rival, “You think you’re gonna take her away, with your money and your cocaine.” The record company wanted him to change “cocaine” to “champagne.” Petty wouldn’t back down. Champagne, he said, made no sense, in this context.

Five years later: Petty and the Heartbreakers were headlining Boston Garden. With his ringing Rickenbacker guitar licks and slightly nasal voice, Petty’s sound was classic and lean, pitched between the Byrds and the early Rolling Stones. Petty shared with Bruce Springsteen the ability to take familiar stylings and treat them like discoveries, thus reinventing them.

The coup de grace that night was “Here Comes My Girl," in which Petty told of a working life that offers no reward and yet is made tolerable by the simple fact that his girl is coming to see him. Lead guitarist Mike Campbell and keyboardist Benmont Tench accelerated into a shivers-up-and-down-the-spine bridge, preparing for Petty's sweep into the chorus. When he sang "We're gonna last forever, I can't begin to doubt it," he wasn’t kidding.

Later, he took a few different tacks — trash rock (an almost elegant cover of "Louie, Louie"), dramatic ballads ("Breakdown") and all-cares-to-the-wind exuberance (a cover of the Isley Brothers’ "Shout"). Whatever the intent, Petty's idea was to run with that emotion, to make every word, every guitar lick count.

Warren Zanes — former Del Fuegos guitarist, former vice president at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and current director of Little Steven’s Rock and Roll Forever Foundation — wrote a definitive Petty bio that was published in 2015. He and Petty struck a deal. “Tom said he didn’t want it to be authorized,” said Zanes, who met Petty when the Del Fuegos opened for them in 1987. “It was based on his own reaction to authorized books. He said he feels like when he sees that on the front top of the book, he knows it’s going to be bulls---, an inside, whitewashed account and he said, ‘I want this to be your book. Not ghost-written, not co-written, not authorized.’ The only thing he asked was the opportunity to read it before publication and respond to anything he felt the need to respond to. And he stuck to that agreement.”

Among the things revealed by Zanes: Petty’s heroin addiction. “I stepped into this territory hesitantly,” Zanes said. “This is tricky stuff to talk about. Tom made this particular choice to deal with this kind of pain.”

It wasn’t a secret in certain circles. Zanes had worked on the 2007 Peter Bogdanovich documentary, “Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers: Runnin’ Down a Dream,” where the talk about Petty’s heroin addiction was cut at Petty’s request. (Zanes also wrote the companion book to the film.)

This time around, in “Tom Petty: The Biography,” Petty wanted the story to be told. “Our main point of discussion,” Zanes says, “was his concern that if there could even be one kid out there who could romanticize drugs because they read Tom Petty’s story. I certainly would like to think the account in the book is not romantic.”

It was not. If it began with heroin being a place to take refuge, it ended with the drug as its own prison. Zanes said Petty kicked heroin with doctors’ supervision and it included “a hardcore blood transfusion.” The heroin period, Zanes said, was in the rear-view mirror. “My understanding is once he beat it, he beat it. The guy that I’ve known for the past several years shows no signs.

“This is really a guy who slammed up against midlife and was forced to confront a lot that had been waiting for him — his childhood, his mother’s illness, losing her, the trouble in leading a band, the trouble in his marriage. It all comes down at once and he is a guy born and raised in rock ‘n’ roll. He knew there was something there for when the pain gets to be too much; he regrets his choice in picking up heroin but that’s what he did. And when he got past it, he was past it.”

Petty grew up in rural Gainesville, Florida. His was not a bucolic, nor privileged, life and his desire was to use rock ‘n’ roll as an escape. Zanes’ book is about how Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers formed out of Mudcrutch (which reformed and played club gigs, including Boston’s House of Blues, during the summer of 2016.) It’s about how Petty maintained his band’s existence in the face of intra-band struggle and difficult personnel decisions, how he tried (and sometimes failed) to be a benevolent dictator. And, it’s very much about how Petty has channeled most of his emotion and passion into his music, sometimes at the expense of real-life relationships.

The Tom Petty you hear roaring through “Even the Losers” is not the Tom Petty you get off-stage. “When you sit down on a couch next to Tom, he’s pretty reserved,” says Zanes. “He’s got a lot of intelligence, a lot of humor and he knows how to craft a sentence. He’s highly engaging, but the power of emotions goes into the songs. He lives differently in his songs than he does in his life.”

Petty recorded three solo albums (that is, sans Heartbreakers) and from 1988 to 1990 was part of the studio supergroup, the Traveling Wilburys, with Roy Orbison, Bob Dylan, George Harrison and Jeff Lynne.

One of the running themes of Zanes’ book is who Petty is in relation to the Heartbreakers. He was the lead singer and main songwriter, but he liked being part of a band. Yet, sometimes he liked the idea of going solo and working outside the band. Over time guitarist-singer-songwriter Campbell began to be considered a near-equal partner.

Zanes quoted keyboardist Tench as saying, “It’s Tom’s band, it’s Tom and Mike’s band, it’s Tom’s band, it’s our band, all of us, but it’s Tom’s band, you know.”

“When he said it,” Zanes said, “I was like that’s it. I think he thought he was not really making sense and he was making perfect sense and I loved it.”

When Petty played Fenway three years ago, he was following Springsteen’s track in proving that bracing, boomer-centric rock ‘n’ roll can be played in ballparks by in-shape sexagenarians. Petty was feisty in songs and laconic between. The music often straddled the fine line between melancholia and celebration. The most downbeat thoughts — in “Mary Jane’s Last Dance” or “Forgotten Man,” say — were wrapped tightly around rock ‘n’ roll that blistered, music that reached out and grabbed you and somehow sent the message that, if only for a night, rock ‘n’ roll can pull you through.

Petty drew from a reservoir of struggle, failure even, and ended up with declaratory celebrations. In “Free Fallin’,” that free fall never sounded so blissful, even though the lyrics suggested something much more tangled. Same with “Runnin’ Down a Dream,” near the end of the show. The tale of a long drive and dead ends, it was positively scorching with its climactic build of tension and release.

There will no doubt be a flood of tributes coming from other musicians. I think this one will be as sweet and on point as any. It comes from Kinks guitarist Dave Davies.

“Tom Petty and his band toured with the Kinks early on,” Davies said. “I thought he was unique and a beautifully minimalist rocker — classic stylish. He helped put cool and laid-back into rock ‘n’ roll. Tom Petty kept his head when many rockers of his time were too busy trying to be macho and hip and boringly superficial … When I spent time with him, he was polite and respectful. He always seemed a quiet and solitary musician. I loved his band, his approach, his music, his demeanor, his wonderful songs and his exquisite recordings.”