Advertisement

Fighting Words — And Billboards: How New England Universities Battle For Students

Right now, if you drive on Interstate 93 north through Quincy into Milton, Jeff Hecker has a proposition for you.

Between Exits 8 and 9, a billboard the color of the sea exhorts you to “Go to UMaine.” Then, in smaller letters, it goes on: “For the in-state cost of UMass.” Similar billboards grace highways from Connecticut and Rhode Island to California.

It’s a one-two punch: introducing the University of Maine to students and families who might never have considered it, then preemptively lowering the sticker price to the lowest possible level.

The billboards' brazenness got them a place on social media. A Quincy Redditor put it this way: "Shots fired (NOT LITERALLY) at UMASS."

Hecker, provost at UMaine, admits the billboards represent a bareknuckled grab at bright students from elsewhere from a campus, and a state, that need them.

“I was explaining [the campaign] to a Maine legislator, and she said to me, ‘You know, Jeff, that’s not very Maine-ish,’ ” Hecker says.

But she agreed that in the intensifying battle for enrollees — their minds, their tuition dollars and their futures as alumni — this is no time for Yankee indirectness.

The billboards, which are up for a few months this fall, announce a three-year-old program called the Flagship Match.

Under the match, UMaine will discount its out-of-state tuition for students who meet certain academic standards — a “B” average and an above-average SAT score — down to what they’d pay at their home state’s flagship campus, such as UMass Amherst, UConn, URI, Rutgers or Berkeley. (There’s a slightly smaller match for students who don’t meet those criteria.)

Advertisement

The un-Maine-ish billboard campaign arose from defiantly Maine-ish politics.

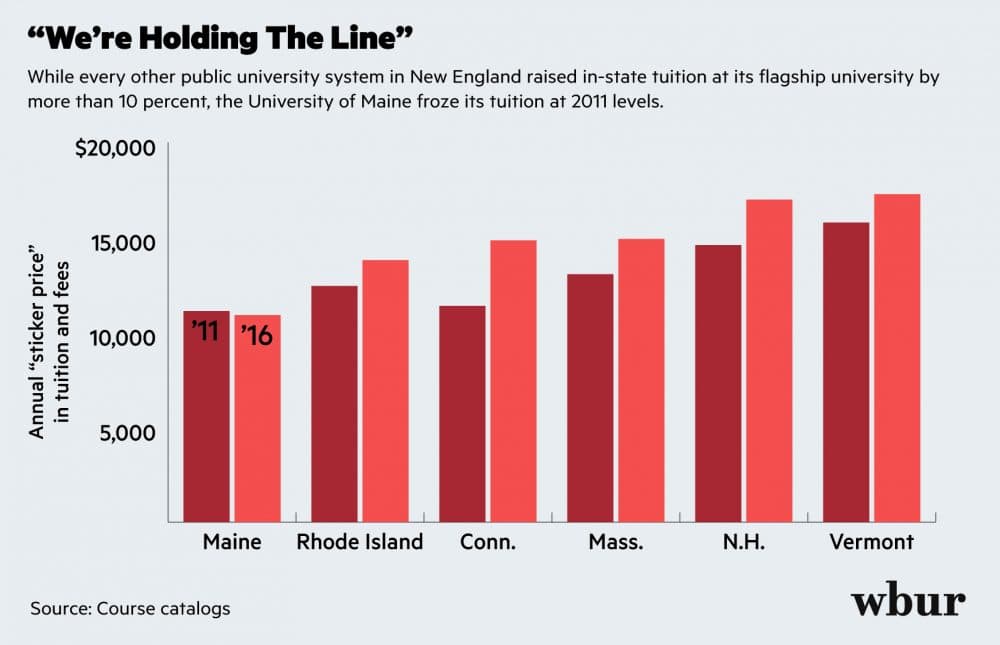

Since the 2008 recession, many states have cut funding to public universities, all but forcing them to increase tuition or fees to cover costs. In the five years from 2011 to 2016, for example, the in-state cost of attending public universities in every New England state rose by double digits, according to the College Board.

Every state, that is, but Maine. From 2011 to 2016, its board of trustees doubled down on the old mission of public universities — serving local students affordably — and didn’t allow the university to increase in-state tuition until last year. So, after factoring in inflation, the in-state cost of attending UMaine actually went down by 2 percent over that five-year span.

UMaine's Hecker admits to mixed feelings on that score.

“The administrator in me says, ‘God, what are we going to do?’ And the Mainer in me says, ‘Good for us, we’re holding the line — trying to keep higher education affordable.’ ”

What that means, Hecker says, is that there’s now “quite a gap” between how much, say, UMass and UMaine expect from each enrolled student — almost $5,000 a year before financial aid.

The Flagship Match is an attempt to capitalize on that gap. If Maine can attract students away from Massachusetts or Connecticut, they can make money while charging them no more than what their home state’s best university would.

That discount is working hand-in-hand with an expanding marketing push, billboards included. It worked for Rachel Hyatt of Darien, Conn. — now a first-year student at UMaine.

Hyatt had hoped to go to school in Boston, but her mother saw a UMaine billboard and persuaded Hyatt to give it a try. They made a vacation of it, visiting Bar Habor on Maine's coast.

When they got to UMaine's homey campus in Orono, Hyatt says she fell in love right away. Plus, money was an issue for Hyatt's family — and UMaine was relatively cheap: "I did fall in love, and I wanted to be here. But [UMaine] being cheaper — it just made it so much easier to choose."

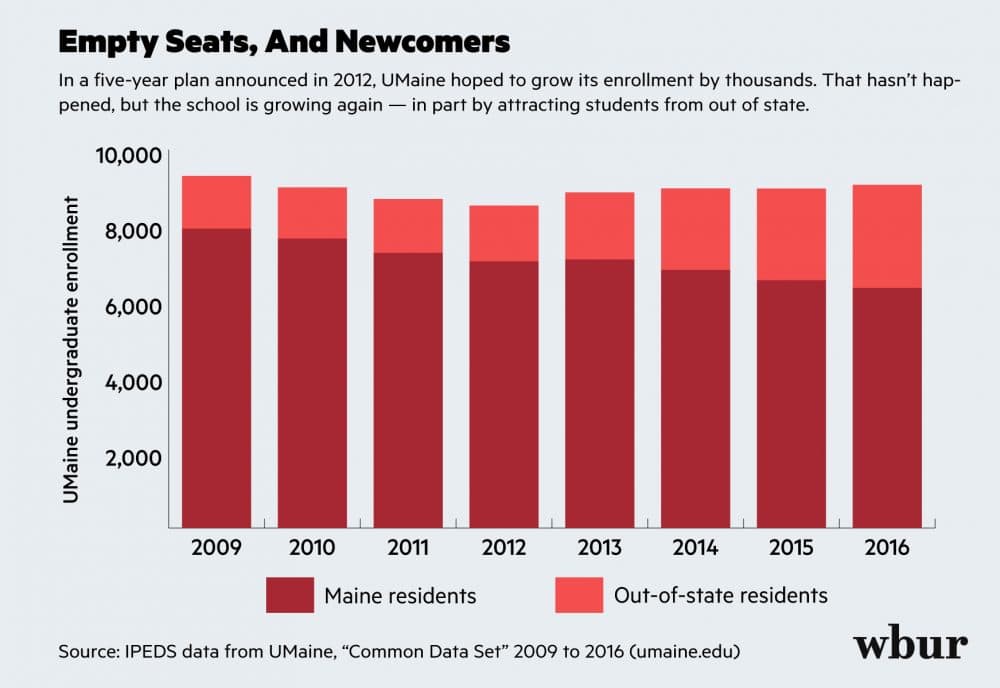

Hyatt's not alone, Hecker says -- the out-of-state offensive is working. UMaine has seen more and more nonresident enrollments since announcing the match. The complexion of its student body has changed: from 15 percent out-of-state undergraduates in 2009 to 30 percent this past year.

Data published by Inside Higher Ed last year showed that the biggest spike in Maine's out-of-state enrollments in recent years came from Massachusetts: an uptick of 81 percent.

You might expect Massachusetts higher ed officials to be concerned about their neighbor to the north. But UMass President Marty Meehan brushes it off, with a bit of big-brotherly scorn.

“The first point would be that the University of Maine obviously has a real issue with empty seats, while UMass has, this year, broken enrollment records," Meehan said. "Anybody that would get into the University of Massachusetts Amherst, for example, probably wouldn't go to the University of Maine."

It's true that more students are applying to and enrolling at UMass schools than ever before. And the system gets more regular recognition than UMaine — one of Reuters’s most innovative universities, a leader in rankings from the U.K.-based Times Higher Education Supplement to the notorious U.S. News and World Report.

But poaching students from a particular competitor was never the point, says Hecker. "Are we trying to pick a fight with UMass? Well, no — they're bigger. Football team's probably better," Hecker says. "But it's a competitive market — I won't lie to you."

Hecker admits the irony that in an attempt to serve Maine students affordably, UMaine actually educates fewer Maine residents — 1,300 fewer than it did in 2010 — while it's chosen to bring in hundreds more students from elsewhere.

It's a change from 150 years ago, when public land-grant universities were established to educate people from their home state — mostly tuition-free. In 2017, university presidents find that sense of duty conflicts with business sense.

Both Meehan and Hecker say they see themselves in a global competition for students, with nearly every other university in the country, public or private.

Meehan says that competition is a good thing: "I think it'll help universities to be nimble." Being nimble might mean shedding costs, opening new programs or buildings -- or putting up billboards across the United States, hoping to lure students north.

This segment aired on October 18, 2017.