Advertisement

The Bald Eagle Population Is Soaring And Now Is A Really Good Time To See Them

Twenty-four people in heavy coats huddled along the shore of the Merrimack River in Newburyport on the last day of January, scanning the icy water and clear sky for something unique among the Canada geese and mallards.

“This is one of our big stops where we stop and look for eagles. Right now I’m just looking for something with a white head out there,” said David Moon, the sanctuary director for Mass Audubon's Joppa Flats Education Center, raising his binoculars at some movement on the water. “When you see a bunch of stuff fly up you look for predators.”

Earlier that morning, before the birders piled into vans for their short trip to various vantage points ending at Plum Island, Moon said he was optimistic that they would see a bald eagle. Just a few days earlier, he saw adult and juvenile eagles jostling for space on the ice floats just outside the Audubon center in Newburyport. He said these sightings are a sign of change for New England, where not too long ago, seeing bald eagles was a rare experience.

“They came close to going extinct,” he explained. “By the time I started birdwatching, it was hard to find one, and I remember my first one because we had to drive a long way to get to this place where a pair was still nesting.”

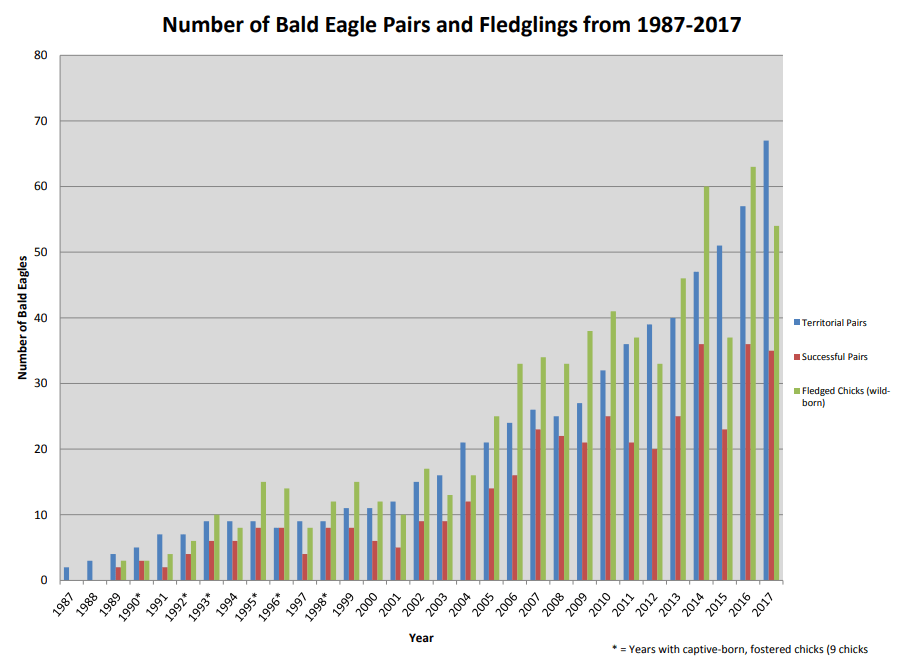

Before conservation efforts began, the last bald eagle nest in Massachusetts was recorded in 1905. In 1989, scientists started to seed the state’s population. In the last few years, the breeding population of bald eagles in Massachusetts has rapidly increased to a record high, according to state ornithologist Andrew Vitz. In 2017, the state had 68 territorial nesting pairs, nine more than the year before.

“That’s really phenomenal,” Vitz said. “This year in all likelihood we will eclipse that 68 number as well.”

Nationally, the return of bald eagles to the United States is considered a conservation success story. In 2007, they were removed from the Endangered Species List as the population reached nearly 1,000 pairs, according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife.

This growth, both within the state and around the country, means that the chance of seeing a bald eagle in Massachusetts is higher than it’s been in generations. That’s because in addition to the reestablished territorial nesting population, the increasing population of North American bald eagles migrate to southern New England in the winter months.

The state doesn't have an official number of just how many bald eagles were in Massachusetts before the population began to decline in the early 1900s, but there are records of eagle sightings across the entire state.

The reason for their disappearance, said Vitz, was largely habitat destruction. At the time, the hunting of birds of prey, paired with deforestation and general water pollution, wiped out the year-round population.

The chemical insecticide DDT, used later in the 20th century, is also a widely cited factor in the decline of the population in North America. While bald eagles stopped reproducing in Massachusetts long before then, Vitz said the chemical contributed to further endangering the community.

“In terms of our nesting birds they were already extirpated by the time DDT was was being distributed,” Vitz said. The national decline affected the number of bald eagles in the state because Massachusetts is often a destination for many migrating eagles as bodies of water freeze in the north and west.

Advertisement

Bringing eagles back was “a hacking effort,” as he puts it. Juvenile chicks were brought in from Michigan and Canada to towers along the Quabbin Reservoir in the '80s after the EPA banned DDT and various federal and state efforts contributed to the protection of eagles and of wildlife areas in the state.

“I think the fact they’re coming back to Massachusetts is really a wonderful conservation story,” said Carlotta Shaw, who drives from Wayland to join the Audubon birding group. “It used to be such a rare occurrence, and now you see them quite regularly if you go to the right spots.”

The Connecticut River and Quabbin Reservoir are still some of the best places in the state to see bald eagles, but the birds have since been sighted as far as the Cape, and as close to Boston as Fresh Pond and the Charles River.

“You see them on the Charles fairly regularly now,” said Michael Pappone, a retired lawyer from Weston and member of the board of directors for Mass Audubon. He said his friends email him to describe eagles that land in their backyards. “I’m always driving as a distracted driver, not with my iPhone anywhere near in sight, but my eyes are cruising up near the horizon pretty regularly looking for something in flight. You know, if someone’s going to see a bald eagle, it might as well be me.”

Andrew Vitz explained that they’re learning a lot about just how well bald eagles can adapt to the presence of humans.

“It is those birds on the edge of Boston that are so surprising,” he said. The traffic, crowds, and noise don’t seem to bother them as much as researchers thought. “At least initially, that was quite unexpected.”

As the population of eagles grows across the Northeast, scientists are tracking these kind of unexpected trends. In Maine, where large swaths of habitat host hundreds of bald eagle pairs, researchers have wondered why the predators are eating another rare bird, the great cormorant.

As reported by NPR, the great cormorants already had their comeback in Maine, reaching 240 nesting pairs in the early 1990s. As of 2016, that number dropped to 40. More eagles, less great cormorants.

While there aren’t signs of this particular predation in Massachusetts, David Moon said he was shocked to hear of the research coming from up north.

From Salisbury Beach State Reservation, one of the stops on the birding tour, he gestured to the opposite shore of the Merrimack. Perched on a tower at the edge of a jetty, the large black birds looked almost like silhouettes against the sky.

“Of course [in the past] there were lots of bald eagles and great cormorants, and they seemed to somehow have a balance,” he explained, speculating that the decline in bald eagles for multiple generations might have thrown that off.

Vitz said that in Massachusetts great cormorant and bald eagle interactions aren’t a huge concern, but eagles could eventually pose a threat to other nesting waterbirds.

“We want to bring back bald eagles,” Moon said, “but there may be a cost in terms of other birds we like to see or want to protect as well. If a species has a lot of pressures on it and is on the edge of not doing as well, one new thing can really change the dynamic.”

The state estimates there are four to five nesting pairs of eagles in the Merrimack watershed, where the Audubon birders made their trek.

Audubon guide David Weaver pointed up, above the trees across the river. He thinks he has an eagle. It’s flying, so following it with the scope propped on a tripod to his left is going to be hard. Another man stepped up to the lens, hoping to close the distance.

“Quick, eh, too late.” The eagle dived into the treeline.

“Came back,” the man said, eye still glued to the scope.

Weaver put his binoculars to his eyes. Based on the color of the bird’s feathers he estimates it’s about two years old. It takes a bald eagle about five years to get that signature look of an adult.

They were still following the bird in flight when Weaver saw another just below the treeline.

“Going right. Very slow wing beat.” The eagle landed and Weaver adjusted the direction of the scope.

Through the eyepiece, the now-grounded eagle was framed in the center of a circle. Its head was speckled with brown, the markings of a young eagle. Several geese bobbed in the water in front of it. The bird turned to face the scope. It walked forward, hobbling from one leg to the other.

“I just don’t think that the geese are too worried about him,” Susan Yurkus remarked, standing just behind the crowd. Yurkus remembers the days when eagles were hard to come by. She, too, traveled to see her first bird more than 20 years ago, at a dam in Connecticut.

“People really made trips to go to this particular dam, or any place they could really see an eagle,” she said. “So it’s been a big change in that number of years.”

She now lives a block from the Merrimack River, where she said she can see bald eagles fly over her house.

“There are more nests now than when I first came,” she said. “And they’re doing quite well. Thank heaven. I’m very happy about that.”

David Moon said he hoped the cold weather would hold, drawing more eagles to Newburyport for the annual Merrimack River Eagle Festival.

“The public just responds to this majestic predator,” he said, “I think that there’s some awareness that you used to not be able to see bald eagles and now you really can see them.”

As more people report bald eagle sightings, the state uses that information to track the growing population.

“There're getting to be so many eagles in the state that we don’t have the resources to send staff out to look for new nests,” said Vitz. “In terms of finding new, and trying to monitor that population of the new territories, we almost get all of that information from the public.”

The state tags Massachusetts birds with a burnt orange band, and this banding can happen as soon as someone reports a nest. Especially during April and May, when migratory birds have left, the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife encourages birdwatchers to report sightings so they could track the nesting population.

Even if you’re not a pro, the birders of Mass Audubon said you would know if you saw a bald eagle.

“It’s just always just an exciting sight to behold,” said Michael Pappone. “When you spot a large bird in the sky that looks like a two-by-12 plank that’s just cruising along, that is not a red-tailed hawk. That is not a crow. That can only be a bald eagle.”

The Merrimack River Eagle Festival takes place Saturday, Feb. 17 in Newburyport and Amesbury.

This segment aired on February 27, 2018.