Advertisement

COMMENTARY

Former Globe Editor Matt Storin Recalls Covering Chappaquiddick And Ted Kennedy

With the release of the film "Chappaquiddick," WBUR asked Matthew V. Storin, former editor of The Boston Globe, to recount his time as a Washington-based correspondent covering the story.

Friday, July 18, 1969 was a very hot day in Washington, D.C., though there’s nothing remarkable about that in midsummer. In hindsight what was remarkable was that it was the high point of the political power of Sen. Edward M. Kennedy. He was 37 years old and it was widely presumed as the sun beat relentlessly down on the nation’s capital that day that he would be the Democratic Party’s nominee for president in 1972.

I was a correspondent in the Washington bureau of The Boston Globe, four months into what would be a total of 25 years at the paper. I was the junior man in the five-man bureau (of course, the bureau was all men back then) and my beat was confined largely to regional issues. Kennedy, whom I had covered for four previous years for a news service serving smaller New England papers, was a focus of my day-to-day work.

On that Friday morning, I met the senator just off the Senate floor to ask him some questions about a topic I no longer recall. We had a fairly friendly relationship — as did all the Globe reporters in those days (this would change over time for the Globe and in my own professional life), but I recall something different about Kennedy that day. He seemed distracted and ill at ease. I’ve since heard that U.S. Rep. Tip O’Neill, later Democratic Speaker of the House, but then a congressman from Cambridge, had flown up to Boston with Kennedy later that day and also found him stressed and fatigued.

As mentioned, it was hot and humid in Washington that day (a high of 99 degrees, according to records), and Dick Drayne, Kennedy’s press secretary and a neighbor in the Chevy Chase section of D.C., invited me to go for a swim at — of all places — Ted Kennedy’s pool in McLean, Virginia. (We both lived in houses without air conditioning, not so unusual at that time.) Under today’s more refined ethical standards for journalists, I wouldn’t have said yes, but I could write a whole other piece about the evolution of those standards. As the Globe would prove in the next 72 hours, we did our jobs professionally well then as now. The senator turned over access to the pool to his staff in the summer, when he spent weekends in Hyannis Port. Dick and I were alone that night and over a few cans of Carling beer, we chatted a fair amount about the likelihood that Teddy would run for president in 1972. There was nothing unusual about that kind of conversation in those days, and I was always searching for insights.

The following afternoon I had just returned from a local swimming pool with my three young children and was literally still in a wet bathing suit, when my phone rang. It was Jim Doyle, my bureau chief, who told me what he knew — dead young woman, Kennedy’s car, small island off of Martha’s Vineyard called Chappaquiddick. Through a source who had worked for Robert F. Kennedy, Jim had secured an address for Mary Jo Kopechne. He told me to go there.

Driving through a sudden thunderstorm, I arrived at 2912 Olive St., on the edge of Georgetown. A tall, slim, sandy-haired woman was just getting out of her car with groceries and was talking to a local TV news crew and a reporter on deadline from The Washington Evening Star. Those folks left quickly and I helped Margaret Carroll, Mary Jo’s housemate, carry her groceries into the house. Of course she was in a state of shock at the news she had just learned from the other reporters and asked me for details, of which I had few. We sat in her living room for a few minutes.

Not on a ruse but the call of nature, I asked if I could use a bathroom. There was only one, upstairs. At the top of the stairs was a small bulletin board, with a long distance phone bill. As I recall, there were three numbers with the initials MJK written next to them. One of those numbers, in Pennsylvania, turned out to be her parents’.

I immediately went across the street to another house — more young women with groceries, aides to Sen. Jacob Javits (R-NY) — and asked to use their phone. I called the numbers into the Globe’s Boston newsroom and reporter Ken O. Botwright got the first interview with the bereaved parents, Joe and Gwen.

There was an even bigger story that weekend, the first landing of men on the moon — the fulfillment of an aspiration voiced years earlier by President John F. Kennedy. As noted in the film, Ted Kennedy had done some network interviews in preparation for the landing, which would be a triumphant event for the Kennedy family. In Monday’s Globe, following the successful landing, I had a piece under the headline: “Tragedy mars a Kennedy day,” noting that he was in seclusion on Cape Cod on a day the family should have felt enormous pride.

In fact, the political landscape had sustained an earthquake. The immediate verdict from both politicians and the press: Teddy Kennedy will never be president of the United States.

Earlier in 1969, my colleague Dick Stewart and I had gone out to McLean to visit Kennedy on a Saturday afternoon for the purpose of asking that he cooperate on a book we’d write about his life. He didn’t exactly say yes, and he didn’t say no, but I could tell from talking with Dick Drayne that it was assumed we’d go ahead. By July we had not done much work on it, but the week after Chappaquiddick, Stewart emphatically told me he wanted nothing to do with the project. Dick was older and commensurately wiser than my 26-year-old self. I reluctantly agreed with him. We never discussed the book again.

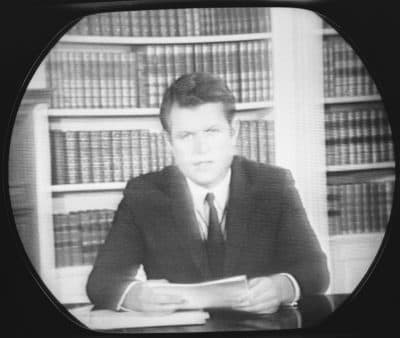

Following his pleading guilty to leaving the scene of an accident, Kennedy remained in Hyannis Port until late August when the Senate reconvened from its summer recess. Ever the competitive reporter, I angled to talk with him as soon as he returned and got his first interview, though most of it he insisted be off the record. The key on-the-record quote, “I can live with myself” was blasted around the world. Of course, this was a self-serving remark and I wonder if, with more experience, I would have let him get away with it. But I was a young reporter on the make and I wanted that exclusive. I feel better about a piece I wrote days later in which I incorporated some of my impressions from that interview.

I described some of the changes I detected in Kennedy: “The ready handshake is not always offered any more. The smile is not the full, toothy one that charmed voters for seven years of public life.” That somber Kennedy is the one that actor Jason Clarke portrays — rather well, I think — in the film.

I ended the piece quoting from a speech Ted Kennedy delivered in Worcester in August 1968 after re-emerging into public life following the death of his brother, Bobby. He said “There is no safety in hiding.” I noted that his days in seclusion with advisers, a main element in the film, had hurt him badly in public perceptions. I concluded, “Whether due to his own inadequacies or bad advice, Kennedy today may feel those words no longer apply.”

Of course Kennedy went on to survive politically, though he faltered badly in opposing Jimmy Carter for the presidential nomination in 1980. Although the Globe continued to cover Kennedy closely, the coverage took a more skeptical, cautious turn from the Chappaquiddick time on. During my time as editor of the Globe, from 1993 to 2001, I endured angry, full-throated complaints from both former Rep. Joseph P. Kennedy, Ted’s nephew, and the senator himself, about coverage. In Ted’s case, the anger seemed to pass quickly.

As for the film, “Chappaquiddick,” it is professionally well done. I expected the strong anti-Kennedy tone, but it is done fairly, and the facts provide all the negativity a Kennedy critic needs. A fictional woman named Rachel serves as a stand-in for the “Boiler Room girls” (the Robert Kennedy campaign aides who were partying on Chappaquiddick), none of whom ever talked much about that fateful evening when their friend died.

Over the years, conservatives have accused the media of covering up for Kennedy and virtually letting him get away with murder. My answer to that would be divided into two parts: the reporting and the opinions of editorialists and columnists.

Regarding reporting, everything we know about what Kennedy (and Vineyard authorities) did wrong we know from the reported stories of the time, although further details of that night emerged when Kennedy cousin Joe Gargan decided to reveal more details in a 1988 book by Leo Damore. The Globe itself, long seen as a paper favorable to the Kennedy family, did a number of investigative stories, examining the story from all angles.

My recollection is that most editorials and columns were sharply critical of Kennedy’s obvious irresponsibility that night, but by and large did not urge resignation or an end to his political career. In this regard, I believe you have to factor in the people of Massachusetts who, certainly with exceptions, had residual sympathy for the senator and his family. This was one year after Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination and seven years after John F. Kennedy’s.

It’s easier to say today that he should have suffered more legal consequences, but back then the majority of his constituents accepted, perhaps grudgingly, his political viability. The fact remains: His standing never again rose to the level of July 18, 1969.

Matt V. Storin was editor of The Boston Globe from 1993 to 2001. Now living in Camden, Maine, he is vice president of the Camden Conference, which sponsors an annual foreign policy convocation.