Advertisement

School Vacation 'Academies' Aim For 'Adrenaline Shot' Of Progress For Struggling Students — And Teachers

This week, most students in Boston are on vacation. But at the 28 schools playing host to what are called "acceleration academies," struggling students and teachers have given up their February and April vacations to get ahead.

The "academy" idea turns 10 this year. Jeff Riley, the state's new education commissioner, formulated the idea back when he was principal of the Edwards Middle School in Boston.

As it has matured, the "acceleration academy" idea has revealed two different forms of education reform that are, at least partly, in conflict. One sees teachers as workers who can be motivated or replaced, and one that sees them as facilitators of academic communities to be encouraged and set free. As Riley assumes control of state oversight of public schools, the academies bear closer attention.

Controversy Surrounding 'Excessing' Teachers

Normally, Chinelle Andrews is a fourth-grade teacher at the Henry Grew Elementary School in Hyde Park. But this February, she served as site coordinator for the school's "acceleration academy."

Andrews is pretty new to teaching. "I came in 2012... '13? '14?," Andrews laughed. "This is my fourth year."

If it felt like longer, it may be because those were four difficult years at the school. Just as Andrews started working at the Grew, Massachusetts' then-education commissioner, the late Mitchell Chester, labeled it one of the state's most poorly-performing schools.

That kicked off a three-year "turnaround" process. As part of the process known as "excessing," many teachers were laid off and asked to reapply for their jobs. Those who stayed faced hours of extra training, uncertainty and possible drops in enrollment — all while officials held the school under the microscope.

Advertisement

"They come in, they interview teachers, they take observations on what they see," she explained. "They try to rate us on how we're doing in certain categories: like, how we doing with parent-family communication? How we doing with instructional planning?"

That process inevitably results in high turnover. Today, Andrews is one of just four Grew teachers to have stayed on throughout the turnaround process.

Teachers' unions have long criticized that heavy-handed approach to struggling schools. Boston Teachers' Union President Jessica Tang said Boston Public Schools has practiced "excessing" for years, with little evidence that it really does "turn around" poor performance. And Tang said it comes at an enormous cost.

"You're tearing apart the relationships between the students and the teachers, the parents and the teachers," she said. "You lose institutional knowledge. It is harmful."

Tang said schools where class sizes are small and teachers are trusted tend to thrive.

'You Get To Do Different Things'

This winter, Andrews put in a lot of extra hours trying to build just that kind of educational environment at the Grew, in the form of the "acceleration academy."

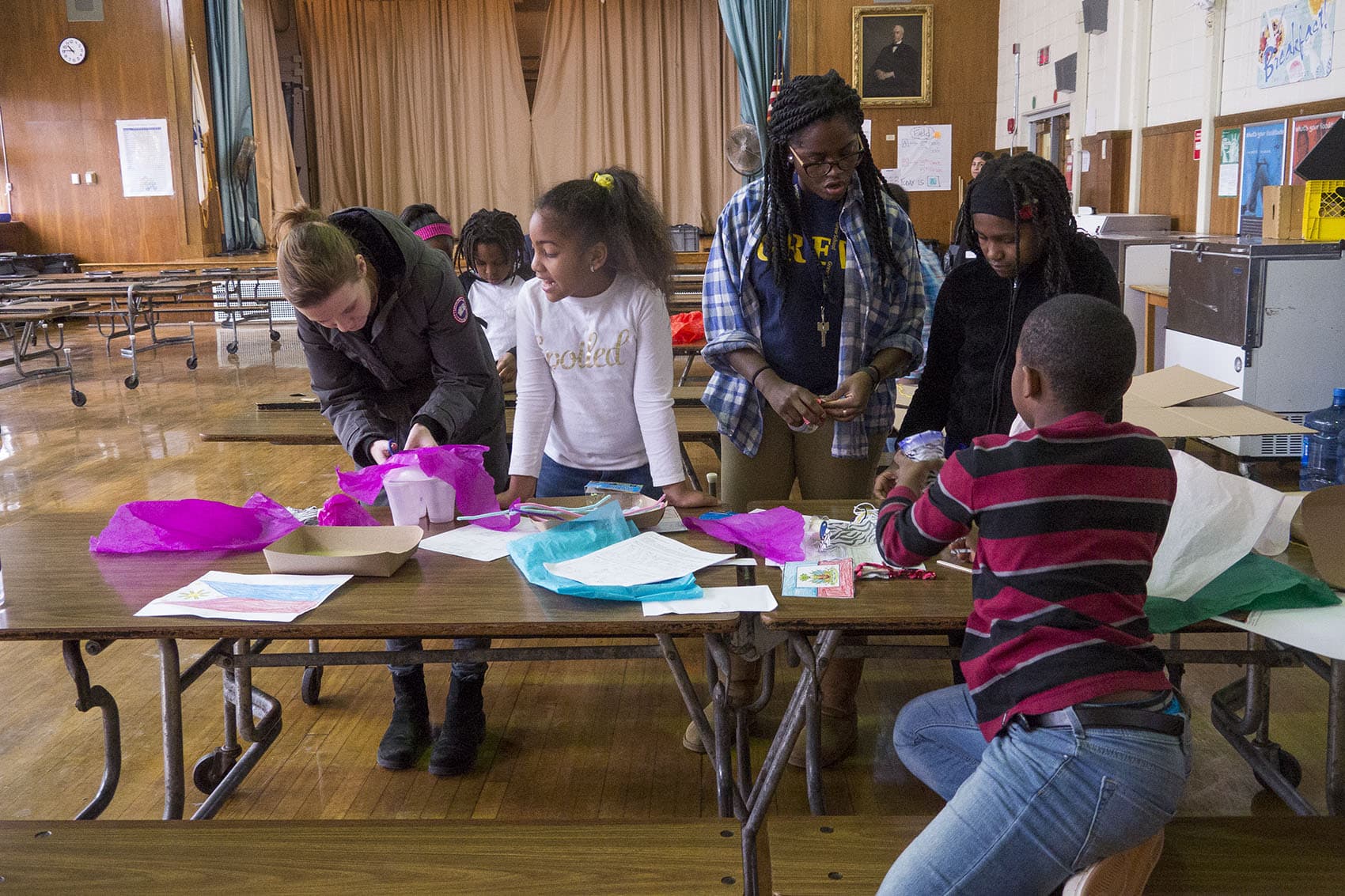

Teachers are paid stipends to work during the four vacation days out of federal "Title I" dollars. At the Grew, the teachers had turned the school cafeteria into a combination workshop, classroom and performance space.

As snow fell outside, three third-grade boys launched into a Caribbean dance they had choreographed themselves, after a week of research. In the back of the cafeteria, other students had built instruments out of household objects while teachers looked on.

Andrews and her fellow teachers designed this interdisciplinary curriculum. It's got STEM, history and what the district calls "culturally- and linguistically-sustaining practices." As part of their lessons, students spoke to parents and grandparents about their family history, and drew on their own stories in developing their dances and instruments.

"Kids are excited by it. They wanna participate, they wanna be in school on vacations because they have these opportunities."

Jeff Riley, state education commissioner

Third-grader Joy Robinson sat designing her Cuban guitar out of cardboard. She said it didn't feel like school.

"Because you get to do different things like dance and math, reading — my favorite thing is basically dance and research," she said.

Her classmate, Maci Lyons, chimed in and said if she weren't at the academy, she'd probably be "at home, arguing with my little cousin."

Raising Test Scores Without Focusing On Test Prep

About 1,500 students have been taking part in similar academies at 27 other Boston schools over February and April vacations this year. Many more have participated in these kinds of programs at schools in Holyoke, Lawrence and Chelsea.

The goal is to turn around academic performance. But Education Commissioner Riley — who developed the "academy" idea -- said the methods of instruction are far from the "drill-and-kill" tactics sometimes employed in the past.

"It's not test prep in any way. It's really about quality instruction," he said. "Kids are excited by it. They wanna participate, they wanna be in school on vacation because they have these opportunities."

Riley made a name in the city by pushing for more learning time and high-quality enrichment, even when those things might have seemed extraneous.

There's some evidence that Riley's strategy works. People were smiling at the Grew. But what's more, education experts at Harvard who studied "acceleration academies" in Lawrence found they increased students' performance on tests by impressive margins.

The studies also showed they did so with minimal disruption to school community, according to Beth Schueler, one of the Harvard researchers who examined the reform.

"It doesn't require replacing all your teachers," she said. "It's just an effort to use the best teachers you already have in your district to get them more face time with the students who need that time the most."

It's somewhat of a paradox: A reform for schools that have fallen behind on test scores is making progress by focusing, it seems, on everything but.

Riley doesn't see it that way. He pointedly decided not to lay off teachers when he assumed control of the troubled Lawrence Public Schools in 2012. He said this kind of educational experience is rare in urban schools.

"The reality is we don't often get to have classes with 10 to 12 kids in them, right? That's not the ideal situation," he said.

He sees the "acceleration academy" as the "adrenaline shot" version: forming small, close-knit "academies" over week-long vacations. You might think of it as an attempt to relocate the love of learning, in teachers and kids alike.

In his new post, Riley will oversee which schools are judged to be failing and what will happen to them.

He said he still believes test scores are an important tool, but he does see problems with the way struggling schools have been handled until now.

"I think there was some blaming of teachers in the past. And I think that's a really wrong way to look at it," he said. "We need to celebrate them, and support them, and recognize that they're on the front lines, doing the work with the kids."

For her part, BTU President Tang said she believes that Riley "gets it."

That's how the acceleration academy over February vacation went at the Grew. This April, another teacher is running another academy. Meanwhile, instead of Hyde Park, Chinelle Andrews is in Scandinavia, on a staff trip to some of the world's best public schools — learning how to be a better teacher.

This segment aired on April 17, 2018.