Advertisement

Review

With Kisses In The Rain And Motorcycles, 'Streets Of Fire' Is Straight From The Mid-'80s Aesthetic Bubble

The lineup for this summer’s “Midnight Specials” series at the Somerville Theatre elicits equal parts amazement and incredulity. Veering away from the genre and horror focus of the Coolidge’s long-running “After Midnite” series, Somerville manager Ian Judge has come up with an eclectic collection of big-screen oddities with an emphasis on kitsch musicals that in many cases must be seen to be believed.

Last week they showed Menahem Golan’s bonkers Adam and Eve allegory “The Apple,” and upcoming bookings include the Gene Kelly and Olivia Newton-John roller disco extravaganza “Xanadu,” as well as Peter Frampton and the Bee Gees’ notorious attempt to make a movie out of “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” Yes folks, they’ll even be screening “Showgirls.”

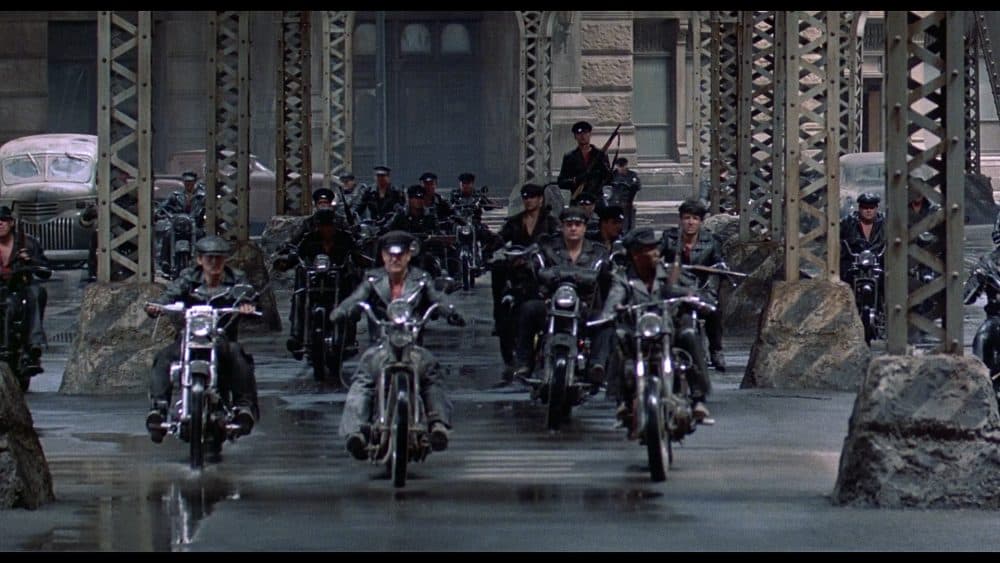

A personal favorite of mine runs this Friday night, director Walter Hill’s dazzling 1984 flop “Streets of Fire.” Billed in the opening titles as “a rock & roll fable,” the film is an extravagantly stylized pulp burlesque that is at once an objectively lousy picture and just about the coolest damn thing I've ever seen. At the time Hill said he was trying to make what as a teenager he would have considered the perfect movie, incorporating “custom cars, kissing in the rain, neon, trains in the night, high-speed pursuit, rumbles, rock stars, motorcycles, jokes in tough situations, leather jackets and questions of honor."

Set in what we’re told is “Another time, another place…” the movie exists inside that weird aesthetic bubble of mid-1980s nostalgia for the 1950s, when rockabilly riffs were backed with drum machines and fashions seemed to be dated from two different decades at once. (Michael Mann’s terrific TV series “Crime Story” really ran with this look a couple of years later.) The pompadours are the size of skyscrapers and every street is lined with neon signs reflecting in the gutters. It’s the kind of movie where two guys have a sword fight with sledgehammers, because it looks awesome.

“The Queen of the Hop gets kidnapped by the Leader of the Pack and Soldier Boy comes to rescue her,” is how Hill initially pitched the plot, borrowing the bubblegum pop iconography of old 45s without filling in much else once shooting started. This is one strenuously mythic movie that seems to be missing a few pages of character development, with Michael Paré’s local hero Tom Cody returning to his hometown after his rock star ex-girlfriend Ellen Aim (played by Diane Lane) is abducted from the stage by Willem Dafoe and a vicious gang of bikers. Dafoe has been bestowed with the priceless villain name of Raven Shaddock and in one of his earliest roles here made a huge impression by managing to be menacing in vinyl overalls.

“Streets of Fire” was filmed on the Universal studio backlot, where this entire city of make-believe was constructed beneath a massive tarp to facilitate the endless night. It’s one of the most strikingly artificial-looking movies to emerge from a Hollywood in that era, ratcheting up the exaggerated “Homer goes to Coney Island” visuals of Hill’s recent hit “The Warriors” to an even more baroque level of comic book splendor. The director issued an edict not to cast anybody over 30 in the picture, to better preserve his illusion of the ultimate adolescent fantasy.

Advertisement

It’s awfully silly, and the old-timey, tough-guy dialogue (penned by Hill and his “48 Hrs.” co-writer Larry Gross) clangs unconvincingly in the mouths of an outmatched cast. A pre-“Ghostbusters” Rick Moranis sneers his way through the picture as Ellen’s new boyfriend/manager while Amy Madigan fares a bit better as Cody’s smart-mouthed sidekick, a role first intended for Edward James Olmos but gender-swapped with little alteration after the actress expressed interest. (Hill famously did the same a few years earlier with his script for “Alien,” in which Sigourney Weaver’s Warrant Officer Ripley was written as a man.)

Tom Cruise was originally offered the part of Cody, not yet a superstar but hot around town for his toothy, volatile performances in “Taps” and “The Outsiders.” He turned them down to make “All the Right Moves” instead and “Streets of Fire” wound up starring Michael Paré, a hunky lummox sorely lacking the magnetism required to carry off such a self-consciously iconic role. Paré didn’t have an easy time on the set, claiming in interviews that he was bullied by Rick Moranis (now that I would pay to see) and that he had trouble interpreting Hill’s directions to “just stand there and be a star!”

One person who had no difficulty doing just that was Diane Lane. The screenplay has been (rightfully) accused of objectifying Ellen as a prize to be fought over by the male characters, but in her scalding scarlet getups and go-go boots Lane is the most elegant component of the film’s production design. There’s a not-at-all-creepy anecdote on the film’s recent Shout Factory Blu-Ray in which a crew member describes how an entire staff of jaded professionals momentarily lost the power of speech when she first walked on set wearing her Ellen Aim outfit. Hill says he intended for her to be a rock 'n' roll Helen of Troy, and when Lane lip-syncs her numbers (her voice was dubbed by Laurie Sargent and Holly Sherwood) you can easily envision her launching a thousand ships, or in this case a thousand Harley Davidsons.

“Streets of Fire” lingered in the popular consciousness long after the movie’s quick exit from theaters thanks to “I Can Dream About You,” an infectious bit of Smokey Robinson-esque songcraft composed by Dan Hartman for the film’s moonwalking doo-wop group, The Sorels. Though performed by Winston Ford in the movie, the subsequent smash hit single and ubiquitous music video featured Hartman’s own vocals, in what my friend Maurice Starr Jr. once told me “is the only time in music history the white guy sang something better.”

But the film’s secret weapon was songwriter Jim Steinman. Best known for his collaborations with Meat Loaf, Steinman had just penned his grandiose masterpiece “Total Eclipse of the Heart” for Bonnie Tyler and the man never met a song he couldn’t launch into the stratosphere with another operatic key change before repeating the chorus a few more times. He’d at first only been hired to write the movie’s opening number, “Nowhere Fast,” but after the production had wrapped soundtrack producer Jimmy Iovine called him with an emergency.

“Streets of Fire” took its title from a song on Bruce Springsteen’s “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” and the film was always intended to end with Ellen Aim belting out the tune. They’d even shot the sequence and torn down the set before anyone realized they didn’t have permission from The Boss to use his song. Oops. So in two days Steinman wrote “Tonight Is What it Means to Be Young,” a magnificently cornball, fist-pumping anthem that encapsulates the movie’s gonzo grandeur far more eloquently than the screenplay itself.

Ellen sings “But I don't see any angels in the city/ I don't hear any holy choirs sing/ And if I can't get an angel I can still get a boy/ And a boy'd be the next best thing, the next best thing to an angel.” Suddenly, almost alchemically, all the picture’s posturing and poses make a grand sort of sense together, and Hill’s teenage dream finally flickers into a reality.

"Streets of Fire" screens at the Somerville Theatre on Friday, June 22 at midnight. See the rest of the summer's lineup here.