Advertisement

Dr. Warner Slack, Electronic Medical Records Pioneer And Champion Of 'Patient Power,' Dies

Harvard Medical School professor Warner Slack, an electronic medical records pioneer who envisioned using computers to empower patients, has died at age 85.

More than 50 years ago, Dr. Slack had a revolutionary idea: "I hoped that the computer would help the doctor in the care of the patient," he said at an event this February. "And in the back of my mind was the idea that the computer might actually help patients to help themselves with their medical problems."

It was a controversial idea at the time, Dr. Slack recalled; some people asked whether computers would replace doctors.

"A rejoinder that I found helpful," he said, "was that any doctor who can be replaced by a computer deserves to be replaced by a computer."

Fast-forward to 2018.

"Within his own lifetime, we've gone to: it would be malpractice to practice medicine without an office full of computers," said Dr. Slack's son, Charlie. Though electronic health records have become a huge industry, he said, his father never lost focus on the patient.

"He was a strong advocate of patient privacy and patients being in control of their own information, and having access to it," he said.

"His interest was only in taking care of patients. At the end of the day, if some patient was better because of his work, he was a happy person."

Dr. Charles Safran

One of Dr. Slack's most quoted sayings was that "patients are the most under-utilized resource in health care," recalled Dave deBronkart, a stage 4 cancer survivor and activist for patient's full involvement in their own care. "He saw the future a half century ahead. He was the patron saint of the movement to get patients involved in health care by involving us in our medical records. And what he saw and talked about even as far back as the 1960s is finally becoming reality today."

For example, there's the project called "OurNotes" at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, where Dr. Slack long worked, that lets patients see and contribute to their own medical records.

"He believed that any patient at any educational level could interact with the computer and not only give us physicians useful information but also could help treat themselves," says Dr. Charles Safran, chief of clinical informatics at Beth Israel. And that was long, long before smartphones and WebMD.

Advertisement

"The technology that he invented and envisioned, he and his partner could have patented this stuff, and they could have been unbelievably wealthy men," Dr. Safran said. "But that was never their interest. His interest was only in taking care of patients. At the end of the day, if some patient was better because of his work, he was a happy person."

Dr. Slack was also happy in his marriage, his son, Charlie, said. This past Saturday, the day he died of lung disease, was Dr. Slack's 62nd wedding anniversary. And he died in his hospital bed in his wife Carolyn's arms.

----

A few excerpts from the obituary his family made available:

In an age before the Internet, Big Data and artificial intelligence, Dr. Slack was among the first physicians in the world to envision the essential role that computers could play in medicine and healthcare delivery. As a resident in neurology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison during the early 1960s, Dr. Slack became intrigued with the possibility that computers could directly “interview” patients, gaining detailed information and valuable insight that could help physicians better treat them.

In 1965, after serving in the Air Force in the Philippines, Dr. Slack—working with Dr. Philip Hicks and other University of Wisconsin colleagues—developed the first computer-based medical history. The results of that first trial, published in 1966 in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that patients enjoyed interacting with the computer, and that the resulting medical histories were more detailed and accurate than those resulting from physician-patient interviews. It was the journal’s first ever article related to computers in medicine.

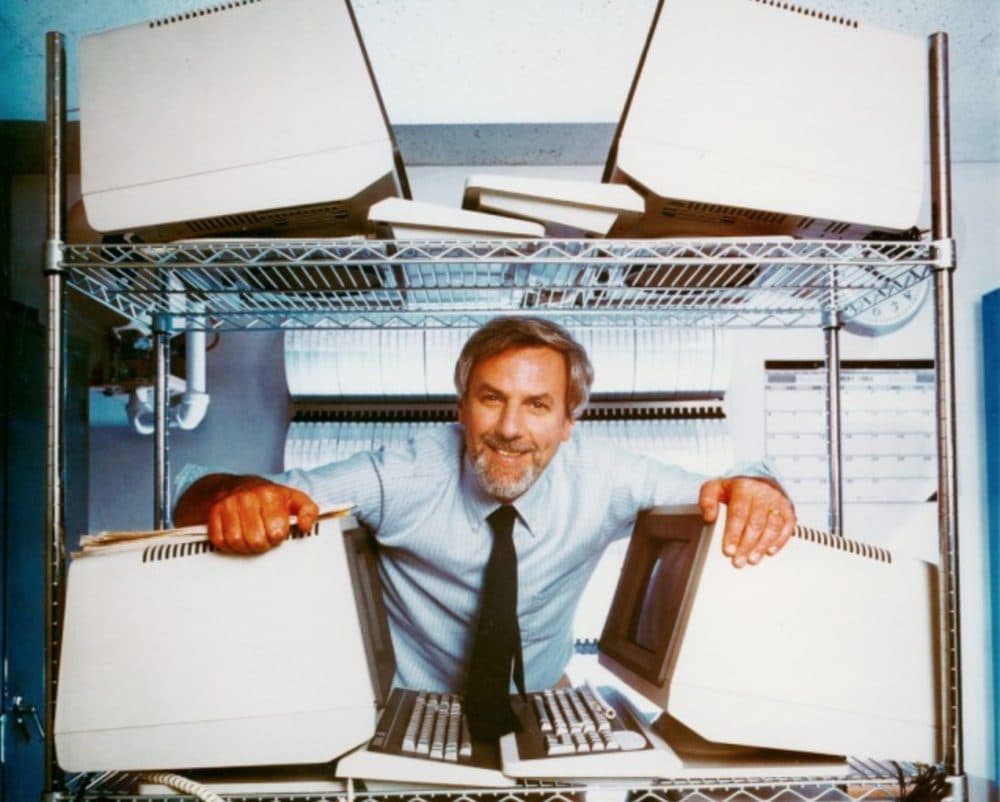

With longtime partner Dr. Howard Bleich, Dr. Slack served as co-chief of the Division of Clinical Computing at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Among their many projects, Drs. Slack and Bleich oversaw creation of some of the earliest and most effective hospital-wide clinical computing systems.

While Dr. Slack’s breakthroughs helped lay the foundation for what is now a multibillion-dollar industry of digitalized patient records, he was concerned first and foremost with the wellbeing and rights of individual patients. He remained a forceful advocate for patient privacy and a critic of any use of computers that he felt reduced human beings to numbers.

His 1977 article “The Patient’s Right to Decide,” published in the British journal The Lancet, put forth a then-radical idea of “patient power”—encouraging patients and physicians alike to overturn the traditionally paternalistic nature of healthcare. Patients, Dr. Slack believed, should play a crucial part in determining their own care. Their insight, he often said, was “the least utilized resource in healthcare.”

Charles Safran, the current chief of the Division of Clinical Informatics at Beth Israel Deaconess, said that one of Dr. Slack’s most remarkable qualities was his generosity in mentoring hundreds of young clinicians. “He envisioned a new field of medicine assisted by computers with patients at the center,” Dr. Safran said. “He lived to see his vision come to reality, and created a legacy in those he treated, trained and loved.”

In addition to his work in medicine and informatics, Dr. Slack took a special interest in standardized testing, and was an early critic of the SAT, then known as the Scholastic Aptitude Test. By claiming to measure innate intelligence rather than learned information, test makers needlessly damaged the self-esteem and prospects of students who performed poorly, Dr. Slack believed.

Consumer advocate Ralph Nader, a Princeton classmate, friend and colleague, called Dr. Slack, “a many-splendored medical doctor in an age of specialization and amorality.” Dr. Slack was a founding member of Nader’s Project 55 (now AlumniCorps), an organization of Princeton graduates devoted to promoting civic engagement. “For all of his adult life, Warner Slack has been a physician's physician, a patient's physician, a student's physician, a citizen's physician, and a champion of peace and justice,” Nader said.

For all of Dr. Slack’s professional accomplishments, family and friends recall most vividly his extraordinary personal warmth, optimism, humor, gentleness and generosity. As a father and grandfather, he never missed a game or concert and always had time to impart wise advice or just the right words of support. He loved family gatherings and hated partings. There was always time to linger over one more mug of coffee, savoring an idea, a memory or plans for the future.

When people came to him for medical advice, as hundreds did over the years, he took each case on as a personal mission, offering guidance, introductions to eminent specialists and personal visits to their hospital rooms.

In lieu of flowers, the family suggests that donations may be made to the Warner Slack Scholarship for Clinical Informatics at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, or to the Joslin Diabetes Center, both in Boston. Memorial Service information will be announced soon.

This segment aired on June 26, 2018.