Advertisement

This Labor Day Weekend, Harvard Film Archive Celebrates The Great American Boxing Genre

When it comes to staying up all night watching movies with strangers, Boston area insomniacs have a seasonal variety of options. The Coolidge Corner Theatre is famous for their annual Halloween horror marathon and every February brings 24 hours of science fiction to the Somerville. But on Labor Day weekends, the Harvard Film Archive likes to change things up a little bit, spending Saturday night with a different genre every year. Recent HFA marathons have focused on heist pictures, movies set on trains and the films of Joan Crawford (because let’s face it, the lady was a genre unto herself). This year they’ve curated a fine collection of boxing flicks.

“The Big Fight” begins on Saturday, Sept. 1 and continues through the morning of Sunday, Sept. 2, showcasing six 35 mm features and a short, cheekily listed as “Rounds” in the HFA program guide. It’s a uniformly excellent lineup, but don’t go looking for any feel-good “Rocky” sequels here. This is one tough bill, delving into the darker sides of the sweet science and more often than not leaving these characters with a one-way ticket to Palookaville.

The evening begins with Charlie Chaplin’s delightful 1915 Essanay Studios short “The Champion,” presented with live musical accompaniment by Bertrand Laurence. Down on his luck as usual, The Little Tramp takes to the ring and discovers he fares better when he’s got a horseshoe in his glove. Jolly as it may be, the film nonetheless begins with title card applicable to most of the marathon’s other offerings: “Completely broke. Meditating on the ingratitude of humanity.”

Make sure you bring plenty of Kleenex for King Vidor’s 1931 “The Champ,” which kicked off the venerable tradition of boxing pictures as male weepies that continues today with the likes of “Million Dollar Baby” and “Creed.” The incredibly endearing Wallace Beery stars as a boozy, over-the-hill lug who gets back in the ring for the sake of his precocious, fast-talking son — played by 8-year-old Jackie Cooper in one of the screen’s all time greatest child performances. Not to be confused with Franco Zeffirelli’s soapy 1979 remake (which even as a little kid I spent wishing Jon Voight would just die already), “The Champ” is about as effective as old-school Hollywood melodrama gets.

A boxing picture with one glove steeped deep in film noir, Robert Wise’s 1949 “The Set-Up” is a marvel of stomach-tightening dread. Robert Ryan stars as an ex-contender so washed up his crooked manager doesn’t even bother informing him that their latest fight is fixed. (Why tell a guy he has to take a dive when he’s just gonna lose anyway?) You can probably guess what happens next. Based on a narrative poem by original New Yorker editor Joseph Moncure March, this exquisitely tight 73-minute movie ticks by in real time, with Milton Krasner’s stark, chiaroscuro photography lending the doomy inevitability an almost religious grandeur.

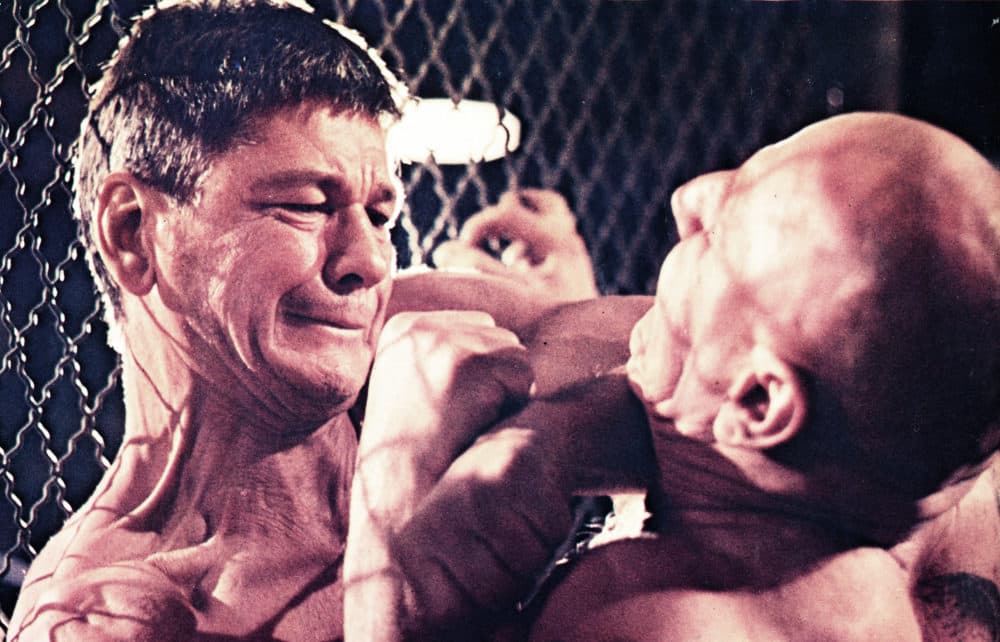

Charles Bronson is at his squinty, stoic best in “Hard Times,” the 1975 directorial debut of screenwriter Walter Hill and probably the evening’s most purely entertaining entry. A laconic drifter passing through the Depression-era South, Bronson hooks up with James Coburn’s cheerfully amoral promoter and a loquacious Cajun played by Strother Martin as the three find their fortunes in the underground, bare-knuckle fight clubs of New Orleans. Lean, mean and artful in its unfussiness, “Hard Times” is one of the purest distillations of Hill’s terse, samurai-cowboy aesthetic. This is the only one of the evening’s selections photographed in color, but its soul is in black-and-white.

To me there’s always seemed something slightly sinister behind Kirk Douglas’ toothy grin, the hint of a sadistic streak put to fine use in the startlingly unpleasant 1949 “Champion.” Playing a prizefighter who pulls himself up from poverty to become a hero to millions, Douglas doesn’t skimp on the character’s toxic narcissism. Based on a story by Ring Lardner, Carl Foreman’s screenplay wallows in the private betrayals and humiliations behind the public adulation, building to a final scene so bitterly ironic it’s practically spat instead of played.

One of the first people we see in Ralph Nelson’s 1962 “Requiem for a Heavyweight” is an impossibly young Muhammad Ali — then just a 20-year-old contender known as Cassius Clay — giving the camera one heck of a whuppin’. We’re locked into the POV of Anthony Quinn’s aging never-was Mountain Rivera, who’s promptly pummeled into retirement by The Greatest in the film’s opening scene. Life after the final bell is the subject of Rod Serling’s screenplay, which he expanded (and significantly darkened) from his popular “Playhouse 90” television drama of the same name.

Jackie Gleason delivers a shockingly effective dramatic turn as Mountain’s miserable manager, looking after the oafish man-child but always putting his own interests first. Quinn’s performance is as oversized as his fists yet impossible not to adore, with Mickey Rooney’s weary cornerman seeing the inevitable, heartbreaking ending coming even before we do. By then the cloud of shame emanating from Gleason could block out the sun.

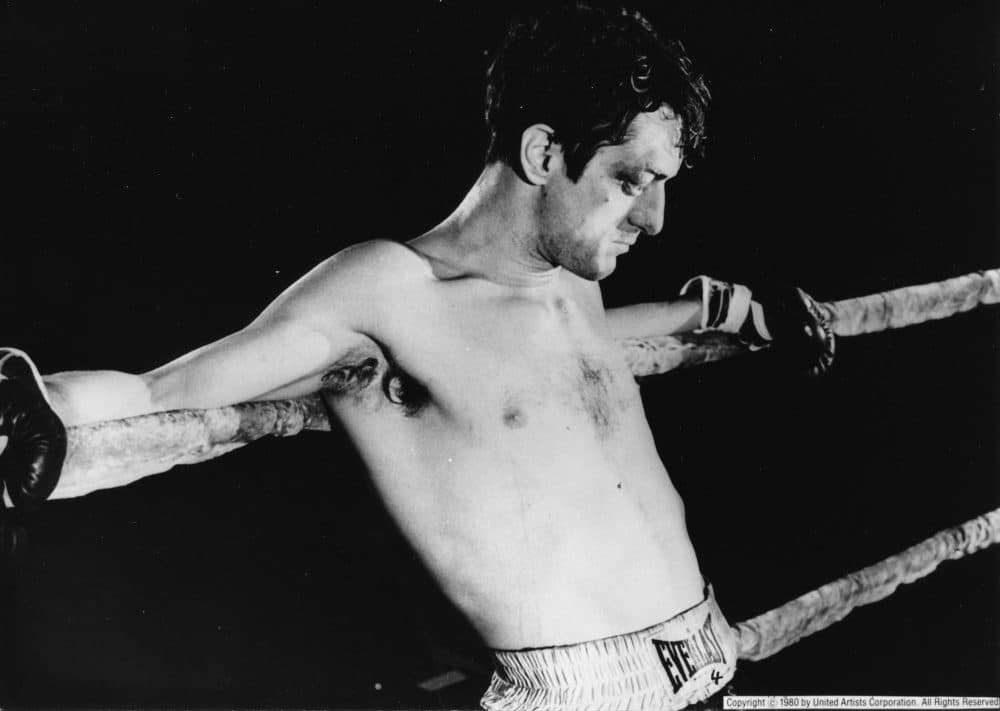

The marathon ends, as it perhaps must, with “Raging Bull,” not just the greatest boxing movie of all time but one of the great films, period. Martin Scorsese’s 1980 masterpiece has little interest in sport, instead using the ring as an extension of his protagonist’s psychological torment, where punishment is meted out and accepted for sins both real and imagined. Robert De Niro’s terrifying transformation into disgraced former champ Jake LaMotta inspired entire generations of actors to play games with their weight for Oscar consideration, but none have ever come close to the depths to which this sad soul descends.

“I’m not an animal,” Jake cries while pounding his head against a concrete wall, an assertion the “Raging Bull” leaves open to question. Indeed, much of the film’s frightening ferocity can be attributed to Scorsese’s later admission that he was using this project to try and purge a lot of his personal demons with regard to women and drugs. But his confession was already built into the film, which closes with a quote from the Book of John: “Whether or not he is a sinner, I do not know... All I know is this: once I was blind and now I can see.”

I don’t go to church much, but that seems like a pretty good way to ring in a Sunday morning.

“The Big Fight” runs Saturday, Sept. 1 through Sunday, Sept. 2 at the Harvard Film Archive.