Advertisement

Commentary

Adding Another '800-Pound Gorilla' To Mass. Hospital Market Will Mean Higher Prices

The Massachusetts hospital market is currently dominated by an 800-pound gorilla.

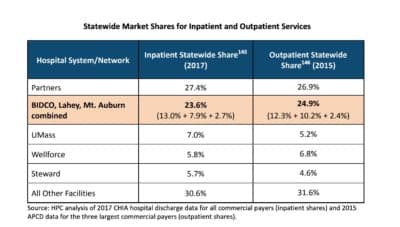

Partners HealthCare is responsible for more than 27 percent of all acute hospital stays in the state, with prices about 30 percent higher than the state average and quality that is often not any better than at other hospitals.

The merger of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Lahey Health, approved by the attorney general’s office on Thursday, will add another 800-pound gorilla. Together, the new entity, BILH, and Partners will be responsible for over half of all acute hospital stays statewide.

Attorney General Maura Healey extracted short-term concessions from BILH in terms of price increases and independent monitoring, and longer-term concessions in terms of access for MassHealth patients and support of safety-net providers.

However, as a health economist, I believe that allowing this level of concentration in Massachusetts hospital markets is a mistake in the long run.

After the seven-year term of pricing concessions expires, we should expect large increases in hospital prices and health care spending, with no overall improvement in quality of care.

Adding another gorilla is not the solution to the anti-competitive effects of having a dominant player in Massachusetts hospital markets.

The weight of the evidence on hospital market consolidation is clear: As summarized by a 2012 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation report, hospitals in more concentrated markets have higher prices and typically provide lower-quality care.

BILH leaders argue that through their merger they will become a hospital system large and efficient enough to provide meaningful competition to Partners. But according to congressional testimony by Martin Gaynor, a health economist at Carnegie Mellon University, “Merged hospitals […] are not systematically less costly, higher quality, or more effective than independent firms.”

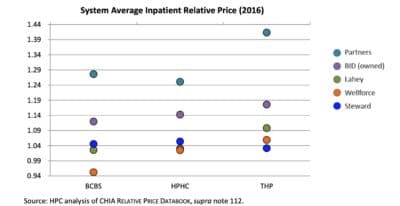

BILH might even provide less price competition to Partners, because they are likely to use their increased market power to negotiate higher prices, once they are no longer subject to constraints on price increases.

In eight of the 12 local markets containing a hospital included in the merger, market concentration will increase by more than the amount that would typically trigger the strictest level of scrutiny by regulators.

According to the merger guidelines from the U.S. antitrust regulatory agencies, this threshold is an increase of 200 points in the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, or HHI, which is a measure of market concentration that ranges from 0 (perfect competition) to 10,000 (monopoly).

These eight markets would see increases in HHI of 584 to 1,614 points, based on an analysis by the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission.

The level of concentration that already exists in hospital markets in Massachusetts is also concerning: All 12 of the local markets that are part of the proposed BILH merger are already in moderately or highly concentrated markets.

This existing level of concentration is important, because hospital mergers in already-concentrated markets typically result in price increases in excess of 20 percent, according to the RWJF report cited above.

But why should we care about these price increases? After all, over 97 percent of Massachusetts residents have health insurance and therefore do not directly pay the prices that hospital systems charge.

However, higher hospital prices result in higher health insurance premiums, which directly harm consumers in the individual insurance market. Higher premiums also indirectly harm employees with coverage through employers, as higher premiums are borne by employees in the form of lower wages.

In their response to the Health Policy Commission report, BILH leaders claim that their prices would not increase as a result of increased market power, pointing to three recent mergers in their systems that have not yet resulted in meaningful price increases.

Advertisement

However, data on hospital prices are only available through 2016, and two of the mergers BILH cites occurred in 2014 (the third was in 2012). Given that pricing contracts between hospitals and health insurance companies typically last several years, there has likely not been enough time to observe a meaningful price increase. Furthermore, these mergers were on a much smaller scale than the BILH merger.

The BILH merger will harm the Massachusetts health care system for much longer than the seven years of price controls or the 10 years the new entity will be subject to monitoring, a lesson we should have learned after the formation of Partners HealthCare in 1994.

Adding another gorilla is not the solution to the anti-competitive effects of having a dominant player in Massachusetts hospital markets.

A better solution would have been (and this is where the metaphor breaks down) splitting Partners into two 400-pound gorillas. But that's a question for another day.

Sam Richardson, Ph.D., is an associate professor of the practice of economics at Boston College.