Advertisement

At The Fuller, Latino Artists Move Beyond Craft

Jaime Guerrero sculpts hot glass, Consuelo Jimenez Underwood weaves fiber and Gerardo Monterrubio shapes clay. Each of these artists works with completely different media, but it turns out, all have something in common. They have spent their careers examining themes around Latino cultural heritage, working in the slim space between art and craft to tell stories that we rarely hear told in either the world of contemporary art or contemporary craft.

Now their works and stories make up “Mano-Made: New Expression in Craft by Latino Artists,” on view at the Fuller Craft Museum through Sept. 8. (A larger version of the show debuted at the Craft in Art Center in Los Angeles in 2017.) The themes explored in this small exhibit are some tough ones, including the plight of unaccompanied migrant children held at borders, the social and environmental impact of border walls, as well as the toll of machismo, poverty, gang culture, abuse and violence on all of us. Opening in December shortly before the government shutdown over immigration policy, the exhibit couldn’t be more timely and offers a glimpse of the diversity and richness of art coming out of the West Coast Latino art scene, particularly from those working outside of traditional mediums like painting on canvas, photography or video.

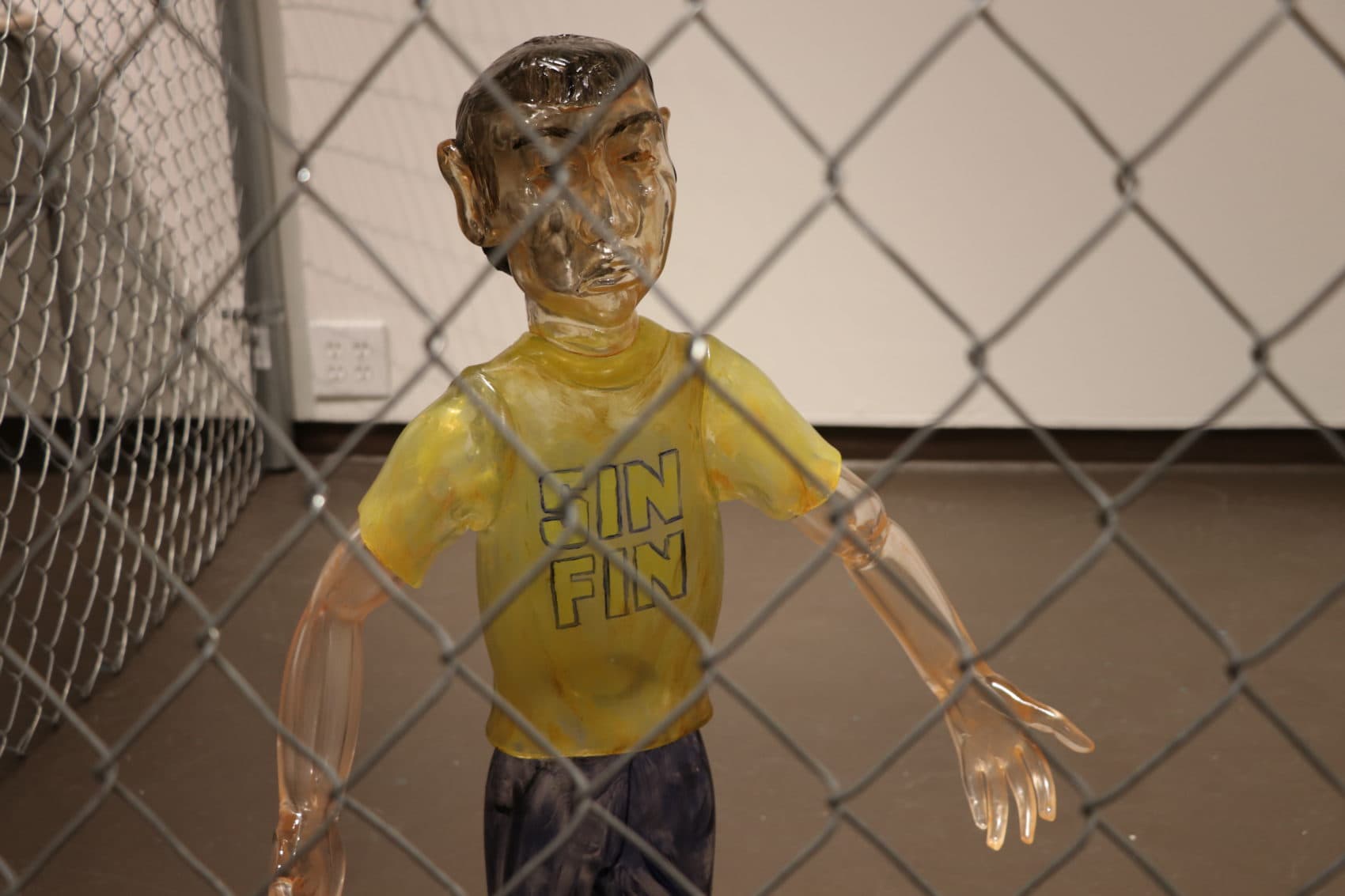

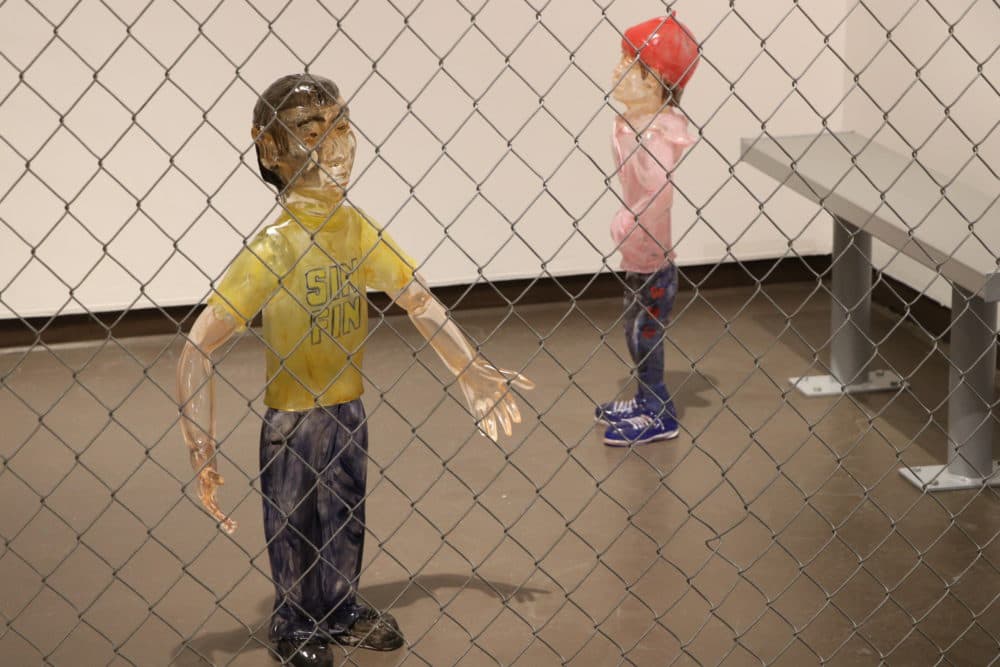

Guerrero’s work may speak most directly to current political debates. His glass children, part of his ongoing “Broken Dreams” series, represent children held at detention centers at the border. Just two have made it into this Massachusetts version of "Mano-Made." Although in past versions, Guerrero has sculpted his children out of clear glass giving them a ghostly, ephemeral quality, this time around, the two children on view are made of colored glass. (“I thought it would be appropriate to add color to these sculptures as a way to humanize them,” he says.)

They stand behind a chain-link fence, confused and forlorn. While the colored glass to some extent de-emphasizes the fragility of the medium, it is in fact the children’s fragility, and also their resilience and sturdiness in the face of trauma, that remains evident.

“The fragility of glass offers an insight into the lives of immigrants, especially young children,” says Guerrero. “These are people leaving their homes and their country behind and losing everything because they fear for their lives. This is a reality that may seem unfamiliar to us. The clarity of the material offers an opportunity to both conceal and reveal these realities.”

Guerrero was born and raised in Los Angeles and is himself the child of immigrants. His parents came from Zacatecas, Mexico in the 1960s. He studied glass under the late Muranese master Pino Signoretto. In 2006, Guerrero began making glass figurative sculptures based on pop and urban street culture, including a series of sculptures entitled "Homies," commemorating a line of collectible figurines by the same name, playing off of stereotypes of Chicanos in East LA. His figures, unlike the plastic figurines they were modeled after, were over a foot in size. And it is, in part, size that makes Guerrero’s work interesting. While his forms and modeling can sometimes seem stilted, it is the technical prowess of wrangling a figure out of hot glass that is most impressive.

Advertisement

“I have been working on these sculptures for several years now and believe that they are more relevant now than ever,” says Guerrero, who is planning to expand on this work for an exhibition at the Pittsburgh Glass Center later this year. “When you hear about children being separated from their families, refugees being held indefinitely, and all this talk about a wall, it makes you question humanity.”

Like Guerrero, Consuelo Jimenez Underwood’s work also couldn’t be more relevant. Underwood was initially inspired to do textiles after glimpsing, as a child, the rebozos that indigenous women wore at the Mexicali-Calexico border near her parent’s home. She has dedicated herself to doing “tough” art using a centuries-old practice that has traditionally been relegated to women. It is her way, she says, to “celebrate Eve, and the thousands of anonymous weavers, knitters and stitchers.” Previously, she says, “the fiber craft (woman’s art, decorative) was at best a forlorn cousin of the craft movement.”

In this version of "Mano-Made" Underwood presents a small selection of her rebozos and a wall installation entitled "Borderlines." The wall piece, which incorporates barbed wire, nails, pastels, fabric, photographs and found objects like beads, presents a line that snakes its way, complete with border crossings, across a desert represented by cloth flowers, cacti and stenciled paw prints. The installation was created specific to the site and picks up on a theme that is a constant in Underwood’s work — that of borders and the environmental damage caused by border walls.

“After seeing my work, I hope to affect/empower the viewer’s ‘border-wall’ thoughts, ideas, and feeling with an alternative vocabulary, then, burden them with an ecological perspective,” she says. If borders are necessary, she says, “then just as necessary is to create, grow or construct barriers that are ecologically crossable by the many undocumented flora and fauna.”

Growing up in California as a daughter of migrant farmworkers gave her a special connection to nature.

“I felt the sky, earth, heavens and could understand the wild nature of the indigenous fauna… Growing up in the borderlands, I have witnessed the destructive force that barriers can create.”

Gerardo Monterrubio lives in East LA and creates intriguing sculptures with a painter’s sensibility. Influenced by his past as a graffiti writer, his work has drawn inspiration from such diverse sources as Classical Greek vases, the Mexican muralists, even prison tattoos. His sculptures read as murals in miniature, telling domestic and personal tales that revolve around survival, masculinity, brutality and mortality.

“I try to keep politics out of my work,” he says. “Instead, I focus on themes that are timeless and that appear in different cultures. But since my work is informed by different aspects of society, such as traditions, belief systems, etc., people often misinterpret my work as political.”

More than about politics, Monterrubio’s work resides at the human level, which he characterizes as “humanity's ceaseless search for a meaning.”

One sculpture included in the show, "Torito" was inspired by poet Octavio Paz’s "The Labyrinth of Solitude" and his study of Mexican male identity. The piece speaks of how violence is used communally by men. The central image is a group of blue figures, including a demonic face that look down on an artificial bull. Lower on the piece, an angry mob pummels people with clubs. On the other side is a picture of Monterrubio’s uncle who was paralyzed, according to the show catalog, because he was beaten for being gay.

Monterrubio developed his drawing skills scrawling graffiti on walls around LA. For him, graffiti-life was an escape from gang life. He went on to study ceramics at California State Long Beach where he found a compelling way to merge his drawing skills with his interest in clay. He says his work today is influenced by, among others, a diverse group of writers and artists including Octavio Paz, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Grayson Perry, Hieronymous Bosch and Francis Bacon.

The “Mano-Made” artists combine art with craft while touching on themes related to immigration, borders and timeless motifs surrounding the human condition. National borders may be hard to erase but the border between art and craft has definitely been crossed.

"Mano-Made: New Expression in Craft by Latino Artists" is at the Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton through Sept. 8. Museum hours are Tuesday through Sunday, 10 to 5 p.m. On Thursday, the museum is open until 9 p.m.