Advertisement

Cities Don't Always Tell You When There's Sewage In The River. A New Bill Would Change That

Gabby Queenan stands on a small lookout point by the Charles River. Behind her, a few joggers brave the cold and cars whiz by on Memorial Drive. She points out the Harvard University athletic fields across the water and the University Boathouse a few hundred yards downriver.

"This is one of the most actively used portions of the Charles River," says Queenan, policy director of the Massachusetts Rivers Alliance, "and I think the public has a right to know what's in their water."

A thin layer of crusty snow covers the ground. She gently kicks it with her boot, revealing a small green plaque.

"Warning. City of Cambridge Department of Public Works. Wet Weather Sewage Discharge Outfall. CAM007," she reads.

"I cannot imagine that a person would look at this [sign] and think, 'Oh this must be an area where sewage is going into the river,' " she says.

But that's exactly what it means.

If you’re wondering how in 2019 we could still have raw sewage in our rivers, the answer goes by an acronym: CSO. It stands for "combined sewer overflow."

Like what you're reading? Get the latest news Boston is talking about sent directly to your inbox with the WBUR Today newsletter. Subscribe here.

Statewide, about 200 active outfall pipes located in 18 cities discharge billions of gallons of sewage annually. And climate change is going to make the problem worse. Scientists predict that in the future, the Northeast will receive more precipitation in shorter, more intense bursts. It's a recipe for sewage overflows.

No one builds CSOs anymore and no one wants the ones we have. But getting rid of them will cost billions and take years, so water advocates are pushing for a more modest, short-term goal: just letting the public know when there's sewage in the water. Queenan's group is behind a bill to do that.

What Exactly Is A CSO?

In most sewer systems in the country, domestic and industrial wastewater — the stuff from our sinks and toilets — flows through one pipe, while stormwater — rain water and melted snow — flows through another. The wastewater ends up at a treatment plant like Deer Island, and the stormwater in a river, stream, harbor or other body of water.

In a combined system, wastewater and stormwater travel in the same pipe. Most days, this works just fine, and the combined water goes to a treatment plant for cleaning. But in a big rainstorm, the volume of water exceeds pipe capacity and overwhelms the sewer system. Rather than let sewage back up into your house or the streets, a CSO system is designed to discharge into nearby water.

Not all CSO outfalls and "events" are equal. In general, overflows happen when a lot of rain falls in a short time, though some cities get them with only a bit of rain or snow melt. Discharges can last an hour or the better part of a day, and contain varying ratios of stormwater to sewage.

Advertisement

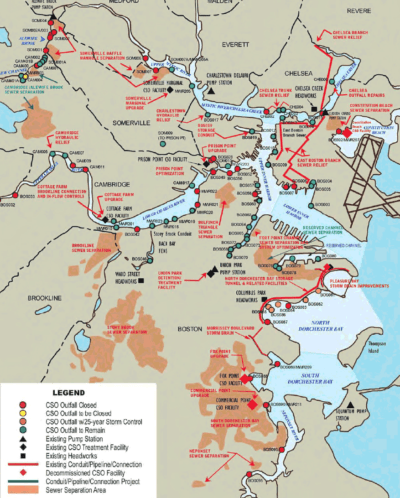

The Charles River has 10 outfall pipes that released more than 29 million of gallons of sewage in 2017, and the Mystic River/Chelsea Creek has eight outfalls that discharged more than 78 million gallons, data from the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority shows. CSOs in the Merrimack River, meanwhile, dumped 770 million gallons of sewage in the river in 2018.

In Massachusetts, sewer operators are required to report CSO events to state and federal agencies. What’s not required? Informing the public.

“I mean, it’s crazy. Where we’re standing right now, there are crew boathouses both upstream and downstream from us, and they’re not getting any notices that there’s sewage going into the water,” Queenan says.

Where Did CSOs Come From?

In the 19th century, the sewer systems in industrial areas like Boston, Haverhill, Lowell and Lawrence consisted of open canals and ditches running parallel to streets. Foul during dry weather, they were a serious public health crisis when it rained. Urban engineers put it all underground in pipes that ended in rivers and streams.

In the mid-1980s, a series of federal lawsuits led to the famous Boston Harbor and Charles River cleanup. The state created the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, which spent $3.8 billion upgrading the Deer Island Treatment Plant and constructing a 19-million gallon underground wastewater storage tank in South Boston. It also closed more than 30 CSO outfalls and built a handful of facilities to partially treat discharges — Cottage Farm and Prison Point on the Charles River, for example.

MWRA executive director Fred Laskey says that prior to the cleanup plan, CSOs discharged about 3 billion gallons of untreated wastewater every year in Greater Boston. These days, that volume is closer to 400 million, and much of it is at least partially treated (screened for floatables, chlorinated and de-chlorinated).

Other bodies of water in the state have not fared as well. Rusty Russell, executive director of the Merrimack River Watershed Council, says hundreds of millions of gallons of sewage are discharged in the Merrimack River every year.

Whether in the Merrimack Valley or in the Charles River, totally eliminating CSOs would be disruptive and cost tens of billions of dollars. Cities would have to rip up sewer pipes — street-by-street — and literally separate the two systems. This has happened on a small scale in some areas of Cambridge and Brookline, but doing it statewide is a much bigger proposition.

“We’ve made a lot of progress and we’d love to be able to say, ‘Oh, we’re going to eliminate them once and for all,’ ” Laskey says. “And that should always be our goal. But what’s practical? What’s a good investment? Where should the money be spent?”

Letting The Public Know

CSOs receive permits under the Clean Water Act, and as part of the permit, most operators must notify the Environmental Protection Agency and state departments of Environmental Protection and Public Health about discharges. Queenan says some permits require notification within 48 hours, but others allow for annual or quarterly reporting.

Some cities let the public know a discharge happened; they’ll put up signs near outfall pipes or post something online. What Queenan's group wants, though, is a uniform process for notification. And she wants it to be faster, more informative and mandatory.

Fourteen states have mandatory notification laws for CSOs. In Vermont, CSO operators have one hour to notify the state, which then sends the information via email or text. In Michigan, operators have 24 hours to report a discharge. In New York, they have two hours.

Earlier this year, three state legislators filed a bill -- An Act Promoting Awareness of Sewage Pollution in Public Waters — in both chambers of the State House.

The bill would require that CSO operators notify local health officials of any discharge within two hours, and that those officials immediately send an email or text to anyone who signed up to receive notification. The message would describe the location of the event, the estimated volume discharged, and any health recommendations, like not boating or fishing in the water for 72 hours.

The bill would also require cities place signs near outfall locations and popular recreational spots whenever there’s an overflow, and that the state collect more CSO information and make it publicly accessible online.

“This is so clear, it’s so obvious,” Queenan says. “There’s sewage going into the water and the public doesn’t know about it. How do you fix that? Create a notification system.”

In the past, similar bills haven’t made it far in the Legislature, but supporters say recent discharges in the Merrimack River have raised public awareness and created momentum for change.

While public notification may feel like a fairly low bar, not everyone is on board with the bill.

“The actual notification part, sending an email or making a phone call, is not the problem. It’s knowing whether you’ve had a CSO [event] that is the challenge,” says Phil Guerin, director of Worcester's sewer system and president of the Massachusetts Coalition for Water Resources Stewardship, a group representing the municipal water sector.

Some CSO outfalls have real-time monitoring and sophisticated metering systems to measure volume discharge. For those systems, a two-hour notification process shouldn’t be a problem, Guerin says. But other systems are more antiquated.

In those situations, “the only way they know if there’s a CSO is to send staff out into the field and open manhole covers and look down into the manhole to see what’s going on 20 feet below the ground,” he explains.

Guerin says he supports the spirit of the bill, but worries how cities will pay for metering. Laskey of the MWRA shares this concern.

“Logistically, it’s difficult to figure out how you could possibly get a meter on these remote locations that would also send a signal,” he says. “So there’s just a certain challenge from an engineering point of view.”

Both men think it’s a technically possible challenge, but they question whether it’s the best use of resources.

Queenan says the 2018 environmental bond bill earmarked $800,000 in grants that cities could apply for to help foot the bill. She also thinks people should demand the state and federal government kick in money to help.

“Nobody wants these pipes," she says. "But cities really need some big dollars to actually fix the issue."

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the amount the bond bill earmarked in grants, and in one instance mixed up the Mystic and Merrimack rivers. We regret the errors.

This article was originally published on March 06, 2019.

This segment aired on March 6, 2019.