Advertisement

At MIT, Rose Salane Unspools The Personal And The Political Like A Librarian

A library bookcase extends across the length of the Bakalar Gallery at the MIT List Visual Arts Center. It is nearly empty, but there are a few dozen books scattered about the shelves, not propped up, but lying flat on their sides.

The books are mostly from the '60s, '70s and '80s, and include titles such as “21st Century Capitalism,” “Manage People, Not Personnel: Driving Fear Out of the Workplace,” and “Combating Air Terrorism.” Between the pages of the books are spare pieces of paper, as if the last reader had marked a particularly interesting passage to return to later.

This is Rose Salane’s evocation of The Port Authority Library, once located on the 55th floor of Tower 1 of the World Trade Center. The library, which served the workers of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey but which was also open to the public, was lost to history after it was closed in 1995 due to budget cuts. Its contents were moved into storage in the building’s basement until they were definitively obliterated during the 9/11 attacks.

These bare and seemingly random facts — a closed library, books on corporate change and management, a terrorist attack — converge in poetic resonance at List Project’s Rose Salane exhibit at MIT’s List Center through May 26. In a suggestive display, Salane unravels a tapestry of seemingly disconnected events to trace the unfolding of history, finding the seeds of our present-day condition in all the details, both personal and political, that stack in time upon one another. Like so many fallen leaves, they may seem fragile and inconsequential — until they clog the rain gutter.

Salane is part historian, part lyrical poet, picking her metaphors with care, allowing viewers to make inferences and associations by focusing close-up on an intimate story before refocusing to take a wide-angle view. As Salane has written in notes accompanying a previous exhibition, she seeks to “enter history through the pedestrian entrance.”

“The simple reality that something has survived long enough for us to encounter it is what makes the past worth digging up to find answers,” she says. “The connections to be made across seemingly disparate vials of information are many, if not infinite.”

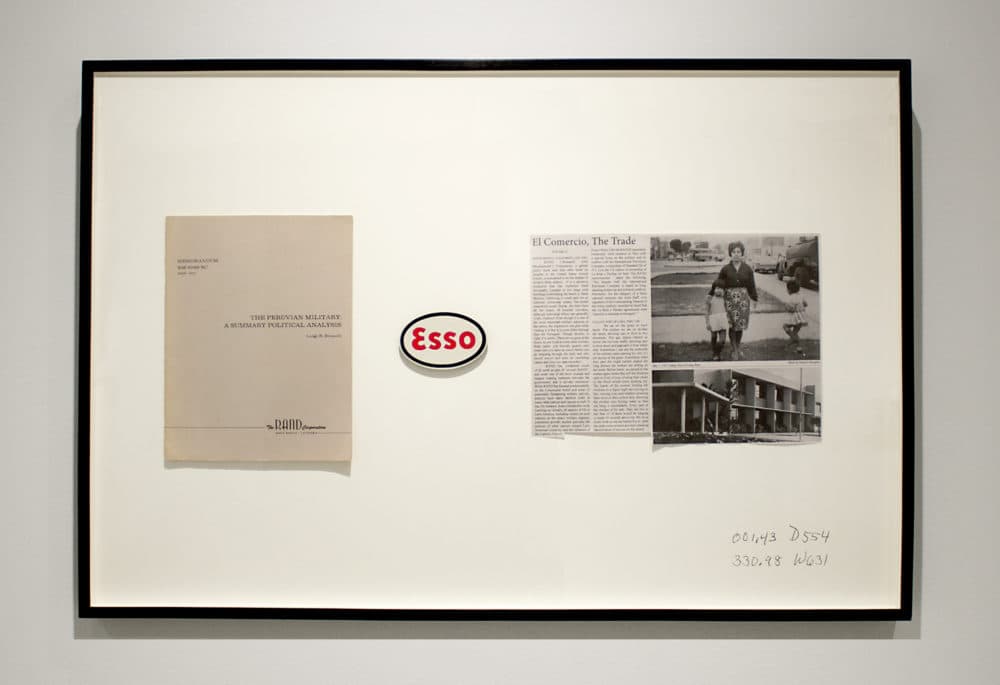

In this current exhibit, she has assembled objects, images and text in what she calls “vignettes of memory.” In addition to the large library shelf and its books, we are presented with five framed works, each of which holds a connection to the volumes on the bookshelves. At first glance, they present what appears to be a newspaper clipping but which we discover are not news reports. Rather, they are shards of memory, psychological timestamps of real-life events. Alongside the clippings, we are presented with small objects and a notation of numbers at the bottom of each frame — the Dewey Decimal reference number indicating the book that has triggered this particular “news” article.

Salane says she sees these framed works “as floor plans of events mapping out time, image and language in fractals.”

A bookcase and newspaper clippings might seem dry fare for an art exhibit but spend some time with Salane’s work and you will discover its beating heart. In this case, a pulse can be found in the characters who inhabit Salane’s articles. For Salane, they are like the people she meets on the streets of her native New York.

Advertisement

“These people approach you and they tell you randomly what they're doing and what they've experienced at this random point in time,” she says. “I feel like that is how I stumble upon so many different things, daily.”

Each stranger’s story can be considered and understood in the context of larger, societal trends and events. Sometimes, the stranger’s actions have direct bearing on what will or is happening, sometimes they presage what will occur, and sometimes they are the result of what has already taken place. Or all those things at once.

And so, in one piece, we are presented with a story entitled “Hands of ’63, ’64, ’65, ’68.” It recounts the story of real-life personage Richard Viguerie, a pioneer of political direct mailing. The story describes how Viguerie, in 1964, pulled together his first fundraising list of those who had contributed to Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign that year. Goldwater lost that election, Lyndon B. Johnson won and signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which Goldwater voted against. The article shares how civil rights activist Julian Bond celebrated Johnson’s signing of the Act (Bond would later go on to be elected to the Georgia House of Representatives) and quotes Democratic Congressman Emanuel Celler who helped draft both the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and 1968. These men are disconnected yet connected in the web of history. Next to the article are cards bearing the signatures of Goldwater, Viguerie, Bond and Celler. There are three Dewey numbers in the bottom righthand corner of the frame. If you take the time to track the number, you will see that they refer to three books on the shelves in the center of the room — "Who’s Who Among Black Americans," “Personal Privacy in an Information Society” by the Privacy Protection Study Commission and “Power, Inc.” by Morton Mintz and Jerry S. Cohen.

For Salane, this story provides insight into what she calls “machine learning by hand.” It was the beginning, she says, of political parties and advertisers carefully culling preferences, categorizing them and spoon-feeding information back to voters or consumers in a way that might appeal to pre-conceived desires or fears. That way of categorizing and manipulating information continues today, culminating in the election of Donald Trump.

“It’s arguably possible to uncover traces of any historical period in the present, perhaps in the most unexpected of places too,” she says. “But to do so is to obtain an understanding with a/the subject/object of study that acknowledges cultural transmission as fact.”

Similarly, a piece entitled, “El Comercio, The Trade,” includes a photo of Salane’s mother, who grew up in Peru before coming to the United States, along with Salane’s grandmother and aunt. In the background of the photo, taken in 1967, we see an Esso gas station, a school bus and military tanks. The newspaper clipping is dated 1969 and describes the RAND corporation, a nonprofit global policy think-tank offering political research and analysis to the military. It juxtaposes this description with a specific memory from Salane’s mother, picnicking in the grass in Lima. Included in the frame is a cover of a RAND report on Peru. We also see an Esso logo and two more Dewey numbers, these referencing “Think Tanks” by Paul Dickson and “Latin America at The Crossroads” by Howard J. Wiarda. Both are on the shelves for perusing.

Salane’s mother’s own personal memory of Peru, the description of RAND and its significance for America’s global influence, the immigrant experience, the exploitation of natural resources, and military and covert actions in other countries — all of it intersects in Salane’s multi-layered piece. RAND is symbolic of how the U.S. has meddled in the politics of distant countries around the globe, often because of its unquenchable thirst for oil.

In the main hallway of the exhibit, we are introduced to the woman who helped spark this entire project. Carol Paszamant is a retired librarian at the New Jersey Department of Transportation. Salane met her in 2018 and discovered she held a floppy disk with the index of all 23,192 books held at the Port Authority Library before its demise. We learn of Paszamant’s penchant for buying flowers for the office, but in this simple personal story are intertwined much bigger themes, including the endangerment of libraries in our digital age, the squeezing of the American worker and global terrorism.

In short, for Salane, everything is connected. There is a pattern and association at hand for every small action and event. The library shelf functions as “the spine” according to Salane, in a sense pulling these events together.

“I like to describe the empty shelving unit as this carcass stripped of the meat and [the books] are the remaining, perhaps still juicy, edible parts. The frame is really important because not only is it a skeletal structure, but it signals a system and a way order functions.”

The books placed on their sides might imply defeat, that history has gotten the better of us, but Salane says the books still have “this ability to be inflated again and be reactivated.”

In other words, at any point, we are free to pick up these bits of history, examine them, and maybe learn something, before it’s too late.

The Rose Salane exhibition is at the MIT List Center for the Visual Arts through May 26.