Advertisement

The Price Of Health

Why Insulin Defies The Normal Rules Of Economics And Keeps Getting More Expensive

Resume

Here's a basic economic principle: The price of a product usually falls over time.

That's often because competitors offer alternatives, or new advances make past breakthroughs less valuable.

Yet none of the typical pressures have driven down the price of insulin, as Everett resident Joanne Rhoton knows all too well. She's a diabetes patient who sometimes takes less than her prescribed dose, to make her supply last longer.

"It's upsetting to have to pay so much money for life-saving drugs," Rhoton said. "There's no way around it."

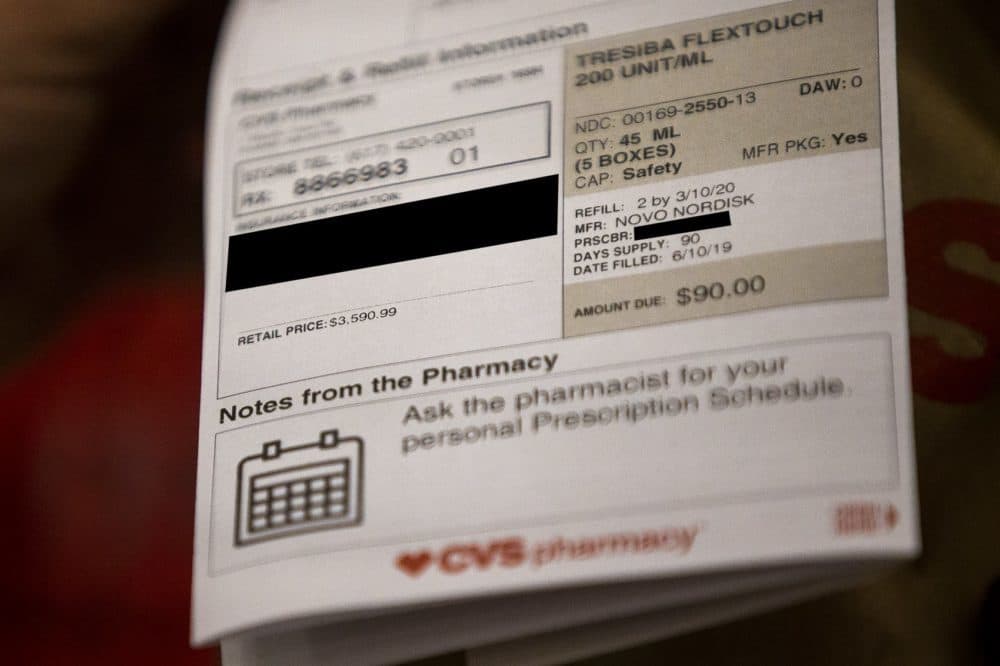

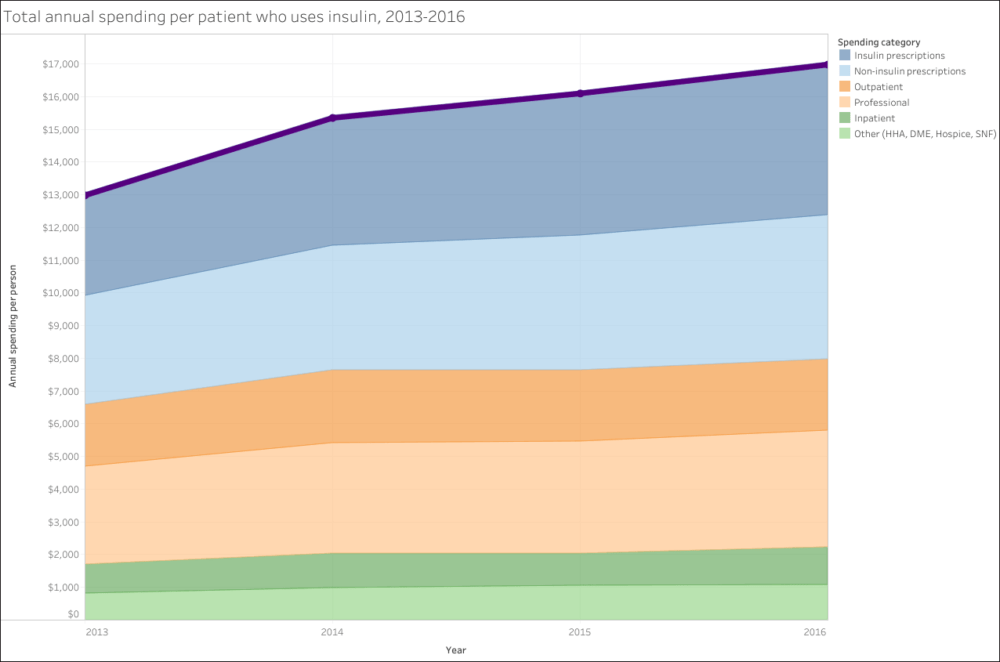

A May report by the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission found Rhoton is not alone in feeling squeezed. Patients in the state spent, on average, 50% more on insulin in 2016 than they did just a few years earlier.

To fully appreciate what's unusual about insulin's price spike, think back to 1996. That's the year that drugmaker Eli Lilly introduced Humalog, the first fast-acting insulin. It's also the year that Nintendo debuted the N64 video game system.

The N64 was state of the art — for its time. It cost $199 at first. But within six months, Nintendo cut the price 25% to match the rival Sony PlayStation. More price cuts followed, until the companies launched new gaming systems.

Humalog insulin, by contrast, has gone from $21 a vial, in 1996, to $275 in 2017. Even adjusting for inflation, that list price is eight times the original.

"Insulin manufacturers charge so much for a really simple reason: because they can," said Shannon Brownlee, co-chair of the Lown Institute's Right Care Alliance, a Brookline nonprofit that advocates for affordable health care.

Here's one explanation for why life-saving drugs like insulin defy normal consumer economics: If a video game system is too expensive, consumers can hold off buying, but with insulin, Brownlee says, "Where is the downward pressure? Customers can't put downward pressure on it because they can't walk away. If they don't take insulin, they'll die."

Humalog isn't the only fast-acting insulin on the market anymore. Novo Nordisk makes one. So does Sanofi. Meanwhile, nutrition research has advanced, providing hope that some people with type 2 diabetes, the kind that usually begins in adulthood, may be able to reverse their insulin dependencies through special diets.

Yet, those developments have not been enough to save patients like Katelyn Hill from price hikes. Hill has type 1 diabetes, which is an autoimmune disorder, so, between sips of a latte on a recent afternoon, she typed 12 grams of carbohydrates into a device that controls an insulin pump on her arm. Then she did some back-of-the-napkin math on her recurring expenses: insulin, test strips, pumps.

"That's a total of $750 a month," she said.

In other words, a lot more than Nintendo's latest gaming system.

Hill used to take Humalog. She's been on a different insulin, Sanofi's Apidra, for the past eight years. But now, she says, her insurance company wants to switch her back.

"So, that's a little stressful," she said. "I think Humalog is cheaper, and that's why they want to do the switch."

Hill's insurer could save some money by moving her onto a half-price version of Humalog that Eli Lilly introduced last month. It's identical to the brand-name original, according to the company.

In a statement, Eli Lilly said it hears patients' concerns and wants to lower their out-of-pocket costs.

Drug makers typically focus on out-of-pocket prices, emphasizing that few patients pay list prices when filling prescriptions. But patients don't get all the discounts they could, according to Boston College health economist Sam Richardson. The reason, he says, is rebates.

Pharmaceutical companies often offer rebates to insurers — cash back to entice them to cover drugs. But, "when you have these rebates," Richardson said, "they are typically not reflected in what the consumer has to pay out of pocket when they are at the pharmacy."

That means if you have a 10% copay, you're probably paying 10% of the list price, not 10% of what's left, after the rebate.

Another cost driver, for insulin and other drugs, is patents, according to Joseph Doyle, co-director of the Initiative for Health Systems Innovation at MIT's Sloan School of Management. He points out that patent laws allow the few dominant insulin makers to minimize competition by patenting incremental changes to their products, which makes it hard for cheaper generics to enter the market.

"From a policy perspective, how strong do we want our patents to be for what we would think of as 'me too' improvements that aren't really major discoveries?" Doyle said. "They're just — they appear to be attempts to extend the life of patents."

In a WBUR poll, 88% of Massachusetts residents said making it easier for lower-cost generic drugs to get approval would help bring down prices "a great deal" or "a fair amount."

Other factors affect prices, too. Even though researchers at Harvard and two British universities estimate a $275 vial of Humalog costs only about $6 to produce, successful drugs, like insulin, have to cover more than just their own costs; their profit margin also has to make up for pharmaceutical companies' losses on therapies that never make it to market.

It's a calculus that frustrates Hill, who argues the human cost should be a bigger part of the equation.

"There's been people rationing insulin because they cannot afford it," she said. "I mean, at what cost?"

Talk of profit margins can seem a bit cold when lives are at stake. But drug companies wouldn't pursue lifesaving therapies if there weren't financial rewards, said Amitabh Chandra, director of health policy research at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government.

"If we give them big incentives, they'll bring new products to market, but they won't charge us a low price," Chandra said. "They only brought the products to market because they could charge a high price and make a ton of money. That's the reason they did it."

The Massachusetts Biotechnology Council contends that pharmaceutical firms' ability to make large profits can actually save money in the health care system, overall.

"If a drug can cure somebody and keep them out of the hospital, it will save trillions of dollars in the long run," said MassBio CEO Bob Coughlin. "And that's what we really need to focus on."

The American Diabetes Association estimates the total cost of treating the disease is more than $200 billion a year, in the United States alone. If insulin and other related costs of treating diabetes are that expensive, just imagine what a pharmaceutical company could charge for a cure.

This segment aired on June 25, 2019.