Advertisement

MIT Scientists Synthesize The Feel-Good Molecules In Kava, 'Nature's Xanax'

For thousands of years, Pacific islanders have made a calming drink out of kava, a root that's been called "Nature's Xanax" and "The Pacific Elixir."

Now, MIT researchers are using cutting-edge science to synthesize the feel-good molecules in Kava.

It's work they say could help lead to new treatments for anxiety, pain and insomnia — and to new insights into other medicinal plants.

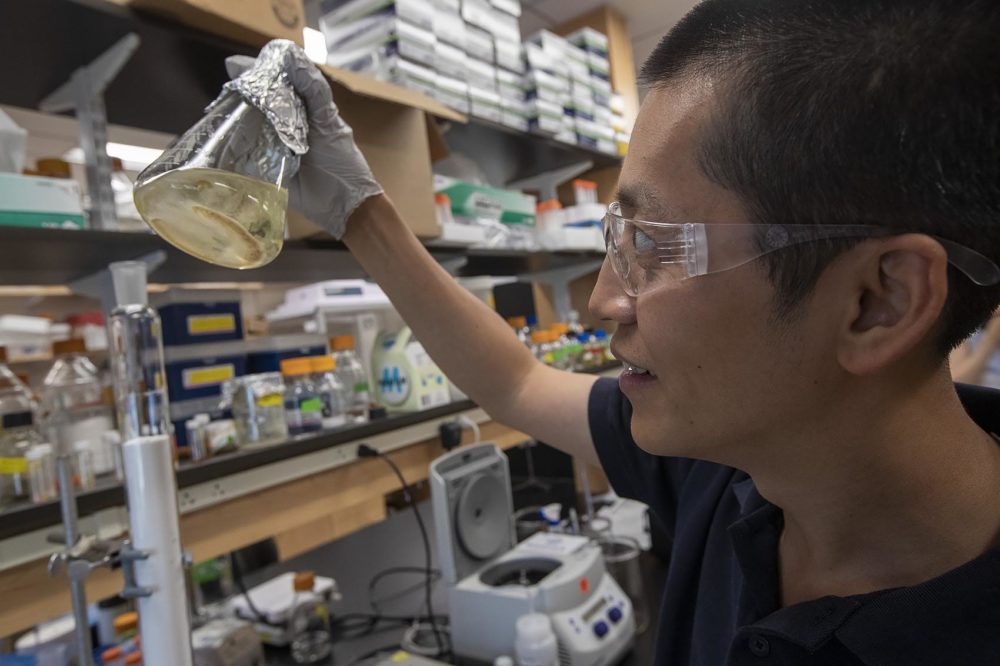

"What we do in our lab is to actually start from plants that have thousands of years of use in traditional medicine," says Jing-Ke Weng, a biology professor and member of MIT's Whitehead Institute. "So we already know there's something in that plant that works to treat some illness, and we just need to find it."

To enter the greenhouse on the top floor of the institute, you have to cross an adhesive mat meant to capture any gene-engineered seeds that stick to the soles of your shoes.

Weng passes growth chambers that resemble noisy refrigerators to reach a big bright space where metal shelves hold seedlings of a spindly weed, arabidopsis, and leafy tobacco plants — all used for experiments in plant genetics.

"It's a secret garden for us," he says. "I like to come here — it's beautiful and relaxing."

Relaxation has been on Weng's mind lately: He and his lab members have just published research laying out the chemistry of how the kava plant makes the molecules that calm people down, called kavalactones.

The lab's experiments also show that "we can engineer this pathway in micro-organisms," says post-doctoral researcher Tomáš Pluskal, and "we can potentially produce these new molecules."

The traditional way to obtain kava on its native South Pacific islands is to cultivate the hard-to-grow root for years before it can be harvested.

The Weng lab method is to analyze kava's complex genetics and metabolism, clone key genes, engineer them into bacteria, and brew up mass-produced quantities of kavalactones.

The lab-made molecules are now being tested in zebrafish, Pluskal says. So are the fish more relaxed? "Actually, they are," he says, laughing. Telltale signs: They're hiding less and clinging less to the walls of their tanks, he says.

Advertisement

In the Weng lab's fish room, stacked high with hundreds of tanks of tiny zebrafish, he compares the fish in water laced with synthetic kava molecules to humans — say, in one of the trendy kava bars opening up lately in New York City or Florida.

"After you drink two or three bowls of kava, you just want to sit down," he says. "You're a little bit dizzy, and relaxed. And fish kind of have a hard time maintaining balance — but once you take the fish out of the water, put in regular water, they're fine."

If the fish experiments pan out, Pluskal says, "then the natural next step would be to partner up with maybe some company and try to develop these compounds into more serious pharmaceuticals."

Fans of natural remedies may not see going from plant to pill as progress. But Weng sees advantages: For one, kava can only be cultivated in the tropics. Now, Weng says, "we can produce essentially the same molecules anywhere in the world."

And, he says, a plant may not be the perfect source of a certain compound if it also produces thousands of other compounds: "Some could be bad for health, could be toxic. Now, we can get access to these molecules in a very precise way," he says.

Also, it may be possible to improve on nature, tweaking the molecules for better effect.

Pill Vs. Plant

Dr. Vincent Lebot, a leading expert on kava who's based on the Pacific island of Vanuatu, calls the Weng lab's new research "very valuable work scientifically, very fascinating."

But he also challenges it on several points. He says the kava buzz has eluded past attempts to synthesize it, because it comes from a complex mixture of compounds.

"It's like a cocktail of different molecules with different properties interacting and having synergy with each other, which produces this very relaxing effect that kava is used for," he says.

Even if Weng's team does manage to replicate that feeling, Lebot questions whether a kava pill should be the goal. He compares it to taking a caffeine pill instead of drinking a cup of coffee in the morning, and kava is seen as a social drink that enhances bonding.

"In the evening, you could have a pill of kavalactones if you want," he says, "but to me, it sounds more interesting to have the natural beverage, kava, which will produce the same effect."

Lebot suggests support for South Pacific kava farmers instead, including free-trade contracts, as they struggle to keep up with rising demand.

"On the other hand," Lebot says, "what Weng's team have done is really useful, because it pushes the limits of kava science further," illuminating how the plant gets its unique properties.

Thousands Of Years Of Medicine

Weng was born and raised in China, and he's also doing research on traditional Chinese herbal medicine, trying to tease apart the critical compounds and the genes that make them.

His methods tap into plant ingenuity that took millions of years to evolve, he says. This is certainly stating the obvious, but plants can't move. Weng uses the term "sessile," immobile.

As animals, he says, "we do well because we developed muscles, and we have brains, so we can actively move around. Plants have to do it passively, so they do everything through chemistry."

We're only at the very beginning of understanding that chemistry, he says, even when it comes to familiar foods like apples or carrots.

"But I really see the next 10 to 20 years being a golden age to rediscover plant chemistry for medicine," Weng says.

He cites estimates that already, half of current medications were derived from natural products, and now new methods allow more efficient drug discovery.

Along with kava, his lab is trying to parse the chemistry behind the positive health effects of goji berries, and the anti-depressant effects of hallucinogenic mushrooms.

Pluskal, the post-doctoral researcher, says lab members have tried kava, and "I can confirm it's a very mild positive feeling of relaxation and slight change in mood."

It wasn't dramatic, he says, but he can understand its social importance for encounters like business meetings, and the benefits of the relaxation it offers for people in constant stress.

So if the lab's work comes to fruition and in a few years, kava or kava-like products become much more available and widely used, what effect might that have on the world?

"I imagine it would be a lot more friendly and positive," Pluskal says.

This segment aired on August 5, 2019.