Advertisement

Trump Calls For A 'Red Flag' Gun Law, Which Mass. Has Had For A Year

Speaking Monday in response to two mass shootings over the weekend, President Trump pushed one gun control measure that's been adopted by Massachusetts and more than a dozen other states: a so-called "red flag" law.

"We must make sure that those judged to pose a grave risk to public safety do not have access to firearms, and that if they do, those firearms can be taken through rapid due process," Trump said in prepared remarks. "That is why I've called for red flag laws, also known as extreme risk protection orders."

Red flag laws aren't new; Connecticut enacted its version in 1999, according to The Associated Press. As of earlier this year, 14 states have laws allowing gun seizures, including Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Vermont.

Massachusetts' red flag law -- enacted last year, months after the Parkland school shooting -- allows a relative or someone else with close ties to a legal gun owner to petition a court for an extreme risk protection order if the individual is exhibiting dangerous or unstable behavior. If granted, the gun owner's firearms can be taken away for up to a year.

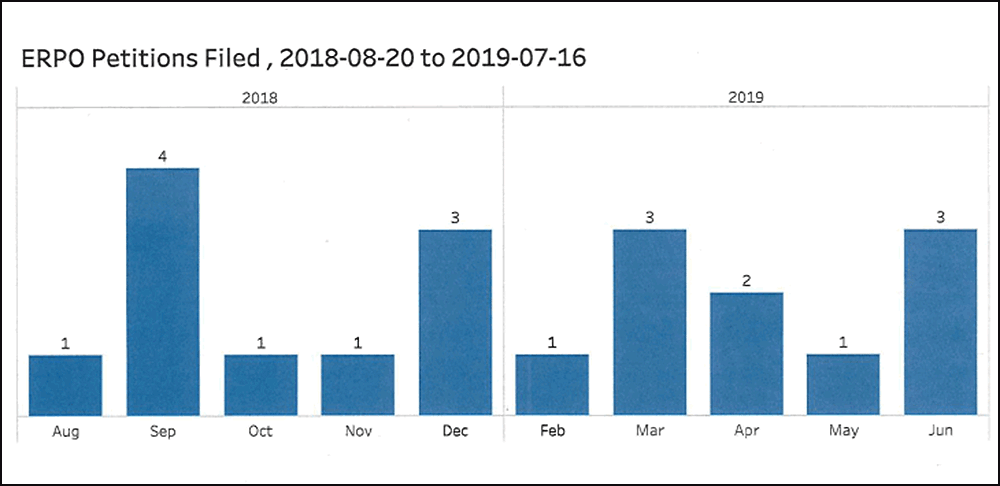

Through mid-July, 20 petitions to take guns away have been filed since late August 2018, according to the Massachusetts Trial Court. In detail:

- Of those 20 petitions, 19 resulted in emergency hearings.

- Fourteen extreme risk protection orders were issued at the hearings; three were denied; two others were "not held" or rescheduled.

- Renewals were sought for 13 orders; so far one renewal was denied and one renewal order was issued.

- In 15 cases, items such as firearms or ammunition were surrendered.

Rep. Marjorie Decker, a Cambridge Democrat who sponsored the bill, said the law is working exactly as it's supposed to, and there's no reason why it shouldn't be replicated across the country.

"Why wouldn't we have a law ... that there should be a very quick way to assess you and to temporarily remove your firearms so you can't hurt yourself and you can't hurt others," Decker said.

The 14 orders issued in Massachusetts so far are just a tiny fraction in the estimated 1,700 gun seizure orders issued last year nationwide, according to data compiled by the Associated Press.

Advertisement

Even before Massachusetts' red flag law went into effect, there were several other ways a person's guns could be taken away. A judge could order a person's firearms removed after an abuse protection order was issued. And unlike in many other states, gun licensing is at the discretion of the local police chief.

"Massachusetts has really created a blueprint of what it means to have commonsense gun laws," Decker said. "We’re a beacon for the rest of the country. We’ve done the hard work and we’ve shown in fact you can do all of this and none of this is about eliminating anyone’s rights to firearms.”

The Massachusetts' Gun Owners Action League opposed the red flag law, saying last year it "revokes due process only for licensed gun owners."

Jim Wallace, GOAL's executive director, said Monday he hopes if other states follow Massachusetts' lead on the red flag law, they focus on the mental health of people who are deemed not able to possess firearms.

"If somebody is to the point where you need to take their civil rights away, then you need to look at, why are they walking among us?" he said.

Decker dismissed that as a National Rifle Association talking point.

Massachusetts' red flag law requires the courts to track the race, ethnicity and gender of the petitioner and respondent, though it doesn't appear that was done in all cases so far.

Five of the petitioners were white; the other 14 did not have their race tracked. Most of the 19 petitioners did not have their gender tracked, but of those who did, five were men and three were women.

Fourteen of the respondents were white, two were black, one was Asian, and three were not tracked. Nearly all of the respondents (17) were male. Two were female.

The data also doesn't say what type of relationship the petitioner had with the gun owner. Police departments can seek protection orders, as can a "family or household member," including a former or current spouse or romantic partner, family member or household member.

Petitions have been heard in 13 district courts across the state, with none seeing more than two cases.

The law calls for penalties against those who file petitions they know are fraudulent. None in 2018 or 2019 so far were deemed so.

This segment aired on August 6, 2019.