Advertisement

At Tufts, Julie S. Graham Retrospective Celebrates An Artist’s Long Career

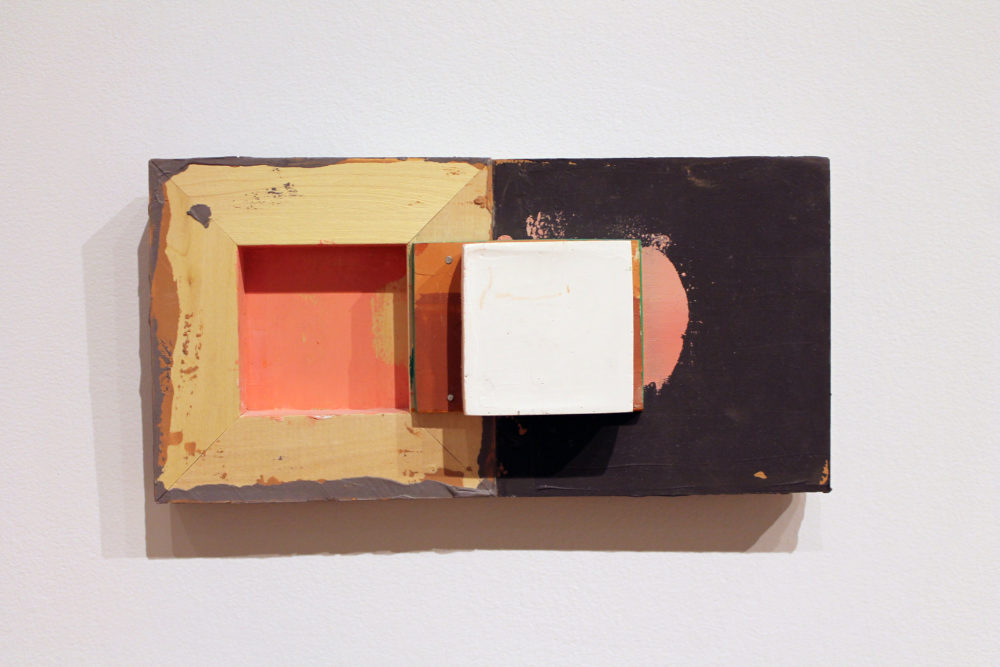

There is something unexpected about the work of the late artist Julie S. Graham. It may be the faded tropical colors of her later works — delicate hospital pinks combined with brash red candy stripes, yawning blacks paired with flirty seafoam or sober olive green. It may be the materials — innocuous wood remnants combined with spackle, plaster, wire and papier-mâché, or perhaps simply rough torn paper and gouache. It may be the compositions — edges are activated by smears, drips and splatters of paint.

Whatever it is, if you’ve seen Graham’s work once, you’ll likely recognize it again, even if it’s from a whole different phase of her career. That kind of unstudied irreverence is hard to forget.

For those who know Graham’s art and for those who don’t, the Aidekman Arts Center at Tufts University is offering up the first comprehensive retrospective of Graham’s work in “Stack, Layer, and Arrange,” running through Sept. 29. The exhibit of about 40 odd pieces traces the evolution of Graham’s aesthetic vision from the mid-1970s, when she created richly textured paintings in muted tones, right up until her death from cancer last year, at which time she was creating small, quirky “sculpture paintings” incorporating color.

Graham was a well-known figure in the Boston arts scene. Not only was she a painting instructor at Tufts’ School of the Museum of Fine Arts but could be found with a finger in nearly every artistic pie in the city. Over the course of her career, she taught at the Rhode Island School of Design, UMass Boston, sat on the board of the Brookline Arts Center, led critique sessions at Maud Morgan Arts center in Cambridge, exhibited in dozens of galleries around town and participated in shows at both the Rose Museum at Brandeis University and the Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton. She was a member of the cooperative Kingston Gallery in the South End, and spent her summers teaching painting workshops in Vermont, the Virgin Islands and Venice, Italy. In her spare time, if there was any, she also served as the visual arts editor at the Harvard Review.

According to guest curator Martina Tanga, who spent part of her summer sifting through a storage unit filled with the contents of Graham’s now dismantled studio along with Graham’s friend and colleague, sculptor Mags Harries, there are certain themes that arise repeatedly in her work.

“She has always looked around her for inspiration,” says Tanga. “At her lived environment, the urban landscape, the natural landscape… She is really looking at lines and composition and the way that things fit together. But she is really curious about things that seem to go unnoticed.”

Though Graham was a formalist concerned with her own artistic inquiry, her art is not precious. Rather, it exudes its own kind of wabi-sabi joy, reveling in decaying, weathered and used things, broken boundaries, the overlooked and unseen. Graham once wrote in an artist statement on her website that she was interested in “the backsides of things,” along with “spaces in between,” “murky light” and “odd juxtapositions.”

“My inspiration often springs from ‘the other side of the tracks’ — urban industrial areas, abandoned buildings, vernacular architecture, minimalist spaces and clustered housing in foreign lands (big boxes in some cases, shanty towns, in others),” she wrote. “Such places and structures are ordinarily overlooked and hidden, but I seek them out.”

Advertisement

In this show, Graham’s preoccupation with geometry and architectural space is clear, even though the artistic challenges she was working to solve changed over the decades. In the 1970s, Tanga says, Graham was largely concerned with surface and materiality. One of her early influences was Mark Rothko, and like Rothko, Graham played with rectangular shapes, with the canvas standing in as a window. In the 1980s, Graham shifted to encaustics, which she also taught at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. She experimented with incorporating natural materials like straw into her work but the paintings remained largely monochromatic. In the 1990s, Graham passed through what Tanga refers to as a “spiritual phase,” in which her paintings alluded to sacred spaces.

The 1996 painting “Hope” incorporates candles and evokes a chapel-like architectural space. Boston Globe art critic Cate McQuaid wrote in a 1998 review that Graham’s candle paintings, created after the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, were “persistent as symbols of ritual and hope.”

In the 2000s, landscape played more of a role, with Graham’s “Vanishing Point” series alluding to map legends, perspective studies and blueprints. But that course of study was not to what Graham would become best known for. The artist, who was originally from Elimira, New York, and who earned her MFA from the Central School of Art and Design in London, would attract attention for her small sculptural paintings made between 2013 and 2017, which include her chunky constructions combining wood and plaster, like “Migrating Square 85” and “Orange Bar 79.” Those pieces appeared in shows at the Kingston Gallery and are a window into Graham’s childlike delight with arranging forms into her own playful geometry. You see the rediscovery of the forgotten and her pluck in combining odd materials. The improbable colors — the hot pinks, vivid oranges and icy blues — are as refreshing as the little dollops of sherbet they recall.

Throughout her entire career, says Tanga, Graham’s amazingly varied work was also incredibly consistent. It was always about geometry, architecture and experimentation.

“I've become really quite passionate about her work,” says Tanga. “I know she was an incredible teacher. She's so loved in the Boston community. She was someone who was incredibly giving of her time and her talents to others. She wasn't such a huge promoter of herself, but I have the opportunity to do justice to her, to really have her work shine.”

In the end, it was perhaps Graham herself who explained what she did best, and what a visitor might find at this retrospective of an artist who left us too soon.

“We never know what's around the next corner — what will happen, or what we'll see,” she wrote in a statement on the Kingston Gallery website. “I'm always compelled by the potential, which is sometimes disquieting, sometimes incomprehensible, and so often thrilling.”

“Stack, Layer, and Arrange” is at the Aidekman Art Center at Tufts University in Medford from Aug. 22 through Sept. 29. An opening reception will be held Thursday, Sept. 5, from 6 to 8 p.m.