Advertisement

Where does EEE come from? Your questions about the mosquito-borne virus, answered

The mosquito-borne virus Eastern equine encephalitis ramps up in Massachusetts every few years. The last outbreaks happened from 2010 to 2012 and from 2004 to 2006. Now it’s back, and there have been four confirmed human cases in the state as of Monday. One person who contracted EEE, a woman from Fairhaven, died over the weekend.

“In terms of mosquito numbers this year, we’ve exceeded the total number of positive samples we had in all of 2012,” says Catherine Brown, Massachusetts’ state epidemiologist.

In severe cases, EEE can cause serious neurological damage and can lead to death or permanent brain damage. Horses seem to be particularly vulnerable, as the virus' name might suggest, says Scott Weaver, a virologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

“There’s a characteristic pattern where they develop facial abnormalities, tongues hanging out, lips not behaving normally,” he says. “When they do necropsies on horses that were infected, you can almost pour the brain out of the skull, it's so devastated by the viral infection.”

That doesn’t always happen to humans, though some 40% of people who do become seriously ill from the virus die. Here are a few things to know about EEE and its history in New England.

Experts agree that you should take reasonable precautionary measures to avoid mosquitoes if you live in a high-risk area for EEE

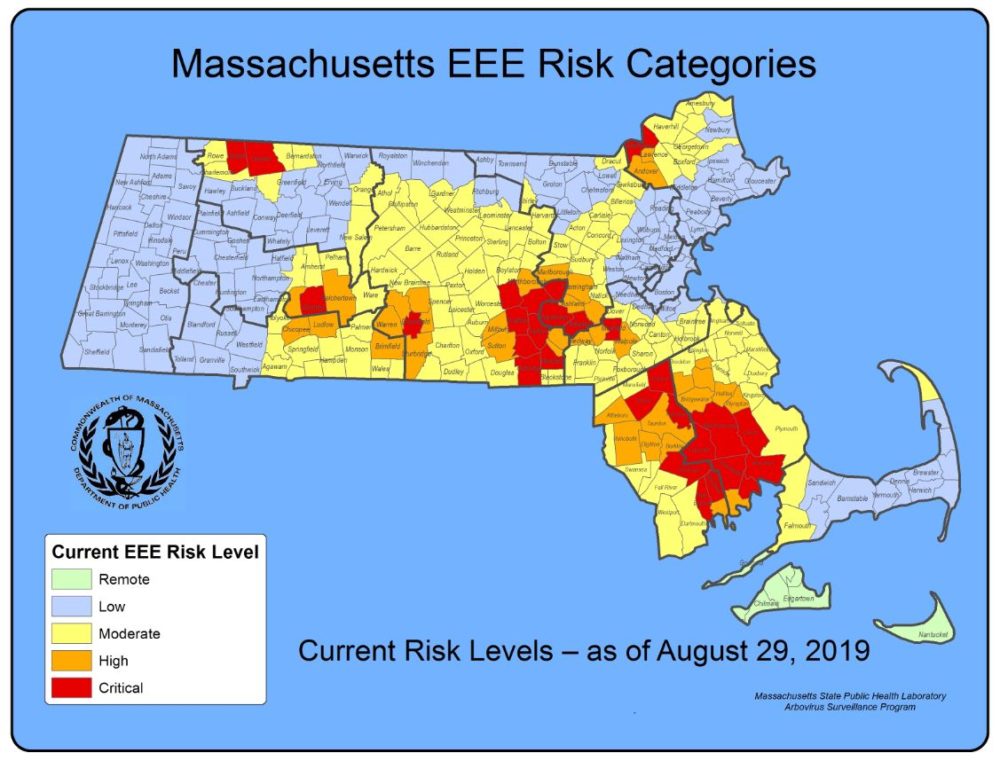

This year, areas in southeastern Massachusetts have some of the highest risk for EEE. If you live in any of these areas, public health officials say to avoid outside activities during the hours around dawn and dusk, when mosquitoes are most active.

“Wear long clothing to protect exposed skin when the weather can permit that. Use mosquito repellents. Dump standing water,” Brown says.

There is no known treatment or vaccine for EEE.

The illness usually begins with common symptoms such as a high fever, headache and chills, but experts warn that it can quickly become dangerous.

"This is a disease that invades the central nervous system, that can progress relatively rapidly to changes in level of consciousness, leading to seizures, coma and about a 40% fatality rate," Brown says.

The virus is rare, and not everyone who gets infected will become sick

Even during high activity periods like this one, Brown says the illness is still very rare. During outbreak years, there are usually no more than a handful of severe cases.

Some evidence suggests that not everyone who contracts EEE gets sick, or some people may experience only mild symptoms. In the 1950s, New Jersey had a large outbreak of EEE, and studies from that time showed that many people had an immune response to the virus but never became seriously ill.

“It seemed like 1 in 20 infections resulted in severe diseases, and the rest are mild,” Weaver says.

Those studies haven’t been replicated recently, so Weaver says there still isn’t a lot of information about how many people are exposed to EEE but don’t get sick.

Most mosquito bites probably don’t transmit the virus

“The infection rates for mosquitoes tends to be low," Weaver says. "Unlikely more than 1 in 100 mosquitoes are infected in a given region.”

EEE probably evolved in South America and arrived in North America at least 1,500 years ago

Based on Weaver’s research, EEE likely evolved several thousand years ago in the Amazon Basin in South America.

“We can’t say for sure, but biodiversity in the tropics is greatest on all continents, so there’s more opportunity for these viruses to find a unique niche," Weaver says.

EEE is closely related to other viruses that primarily live in rodents, so Weaver thinks this virus likely first evolved in rodents and eventually jumped into song birds, which are its primary hosts today. “It’s likely that Eastern equine encephalitis virus changed from rodents to birds when it moved to North America,” he says.

People in North America first identified the virus when it started killing horses, hence the name

“It was just a matter of time before there [were] enough people and horses around and it was really noticed,” Weaver says. “[People] didn’t have a way to know if the virus was there unless humans and horses were around to get sick.”

That finally happened in 1831, when the first recorded cases of EEE resulted in the deaths of 75 horses in Massachusetts.

The threat of EEE wanes with the first frost

It's hard to know just when the first cold weather of the season will arrive, killing off many mosquitoes. In the meantime, state officials have been spraying pesticide in areas where mosquitoes have tested positive for EEE and warning residents to take precautions to avoid mosquito bites.