Advertisement

Commentary

This Map Exhibit Draws A Darker U.S. History — Of Expansion Into Native Lands

Walking through the exhibit currently in Boston Public Library's map center, you'll be surrounded by maps on all sides. There's maps on walls, in cases, stuck to floors, glowing on screens. These are the kinds of historic maps of the United States that we're familiar with — ones on paper that follow a grid.

What we don’t immediately see is that these maps hold a dark and violent histories, ones tied up in the expansion of the country's borders and the systematic oppression of Native peoples.

This exhibit, “America Transformed: Mapping in the 19th Century,” aims to tell those stories. Situated in the BPL's Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, it asks us to reconsider which perspectives are represented in these maps — and which ones aren’t.

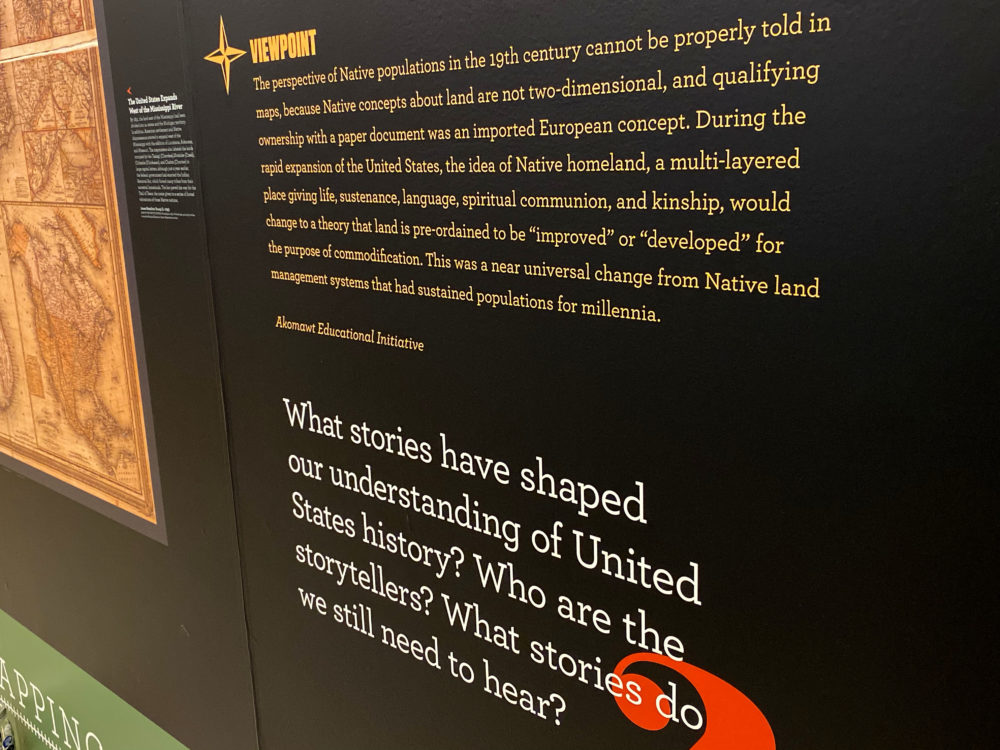

In the first of two parts, the exhibit currently focuses on the Westward expansion (1800-1862) and discusses the Euro-settler removal of Native people from their ancestral lands. Throughout the show, you’ll notice two groups of text, the center’s statement about the map on display accompanied by a statement titled “Viewpoint.” The first gives historic information — when, where, and for what reason the map was made. In the second, Native people tell, in direct language, what the map means to Native people today.

“From the beginning, it became clear that we needed other points of view that we didn’t feel qualified to write,” says Michelle LeBlanc, director of education for the center. “Our new point of view was that, ‘These are maps, this is what they are showing, they’re biased, and there is this whole other world of people who are not heard here.’”

After initial rounds of research and writing, Boston Public Library staff brought in the Akomawt Educational Initiative (AEI) to advise. The group is dedicated to multi-vocal, intertribal education that seeks to empower cultural sites and communities to combat myths and misinformation. They not only read and commented on exhibition text, but also connected the BPL to Native scholars.

Chris Newell (Passamaquoddy), the director of education at AEI, said their work with the map center was driven by their organization’s mission. “We came together to make a social change and a big part of that strategy was shifting the master narrative of American history to put Native people back into it. What we call 're-indigenizing' history.”

LeBlanc said it wasn't enough to involve scholars to check off boxes. “We wanted to acknowledge that these maps have caused great destruction from the way they displayed lands,” she says. The counterpoint brings up the idea that the perspectives of Native populations in the 19th century cannot be shared through maps, because "Native concepts about land are not two-dimensional."

Beyond maps, the exhibition has other objects and posters that dive deeper into the topic.

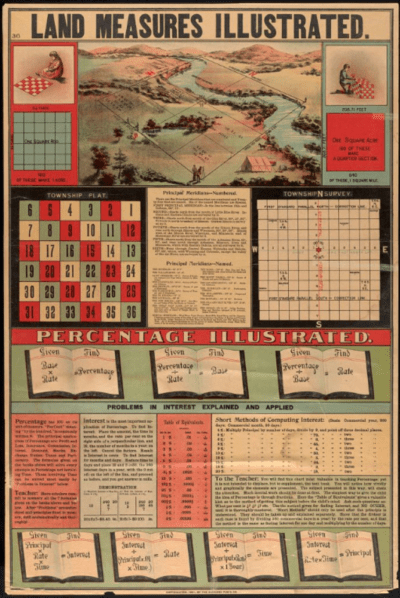

For example, this educational poster illustrates the method of laying out and measuring sections of settler towns. The colorful print in the top section displays a rigid square stretching across a winding river and sloping hills, seemingly fresh for the taking. They measured one mile by one mile, and were for the use of white settlers only.

In response to this, scholar Rebecca Sockbeson (Penobscot Indian Nation) writes, “This diagram reflects the colonial concept of land ownership: packaged up into little squares, as though one can compartmentalize a way of life and sell it.”

Many of the viewpoints were equally bold and transparent. I wondered why they were separate from the main text, however. That the library can be viewed as neutral and without a viewpoint of its own made little sense to me.

I learned, however, that giving these scholars independent, uncompromising spaces to express their take was central to AEI's outreach. Within the viewpoints, the contributors were free to respond with full honesty, speaking their truths as scholars and Native people. Often, it proved difficult.

“Spending time immersed in these documents — and the genocides they represent — required of me, a spiritual space where I could shed the weight and atrocity of these documents and be in balance as I live my life with my family and friends,” endawnis Spears (Diné/ Ojibwe/ Chickasaw/ Choctaw) of AEI said. “There are some big shifts that need to happen in cultural institutions here. We hope this exhibit and this process can help contribute to that praxis.”

The exhibit was personal for me as well. Massachusetts is the territory of Wampanoag, Masachussett, Nauset, Nipmuc and other communities since time immemorial. I realized that much of this exhibit is about unlearning information as much as learning it. As an enrolled member of the Upper Sioux Community in Minnesota, I am also a visitor to this territory known broadly as New England. And whether I like it or not, I too am involved in a broader culture that values and derives power from European-style maps. Several times I traced the tracts of land where colonists would form the state of Minnesota through Native removal and sent photos to my mother.

The second part of this exhibition ("America Transformed Part 2: Homesteads to Modern Cities") will share little-told narratives of the transcontinental railroad, the post-Civil War reconstructions and more on Native history after the Homestead Act of 1862. (It runs from Nov. 9 through May 10, 2020.)

Though not perfect, the boldness and bravery of talking about their map collection in this way is an important foundation on which to build deeper understanding of our country.