Advertisement

In Nova Scotia, Canada's Universal Health Care Beset By Access Issues

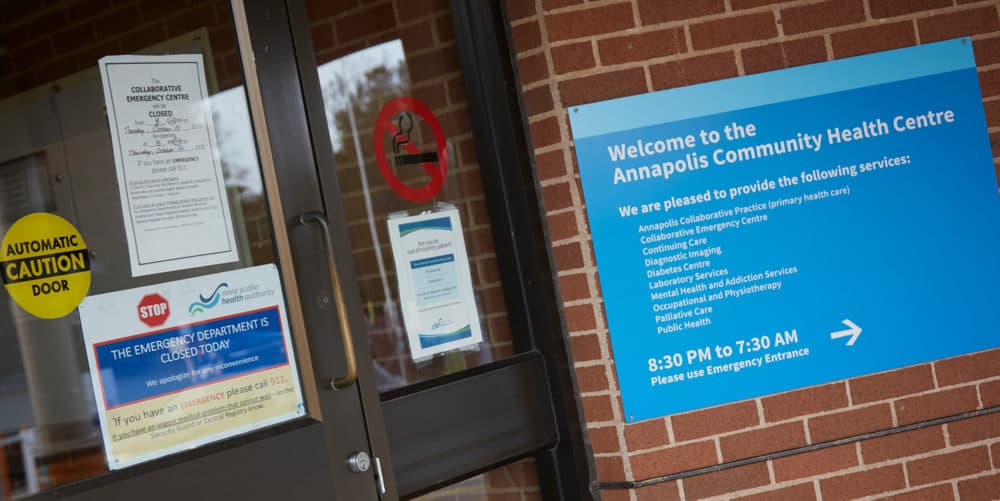

The parking spaces are empty. The doors are locked. And there's a sign on the door of the small community health center.

"The emergency department is closed today," it reads. "If you have an emergency, please call 911."

The Annapolis Community Health Centre is in Annapolis Royal, a small town near the Bay of Fundy in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. Daniel Marsh, the facility's administrator, says it takes seven doctors to maintain a full-time ER schedule, but in the past 18 months, he's been short-staffed.

"Due to retirement and physicians choosing to leave to work in the city, we are now down to five doctors," Marsh says. "Rather than have unexplained and unexpected closures, we have predictable, planned closures every Tuesday and Thursday."

Which means if your emergency is on a Tuesday or a Thursday between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m., you must go elsewhere. Marsh says that often ends up being the Valley Regional Hospital in Kentville, a commercial center 60 miles up the coast.

Dr. Rebecca Brewer is a surgeon in Valley Regional's emergency department. Earlier this year, she says the ER was frequently overcrowded — dangerously so.

She says she dreads a repeat of March 7, when 24 patients were admitted to the 20-bed ER, while a steady stream of outpatients kept coming through the doors.

“When you bring in a patient — no matter what kind of state they're in — you had to talk to them with no privacy. You had to examine them, and then you had to look them in the eye and tell them that they needed to get up out of that stretcher and go back to the waiting room,” Brewer says. "If they were one of the less lucky ones, they would be in a chair, sitting there waiting for, you know, several days at a time, waiting for a bed to open up."

Her colleague, Dr. Rob Miller, describes a chaotic, M*A*S*H-like scenario.

"We're seeing those people in hallways and kitchens, on the floor, in closets," Miller says. "It became almost a running joke amongst our group, as to the most unique spot we could see a patient. It was that crazy."

Without private places to examine patients, he says, confidentiality is not guaranteed.

“You can’t do a lot of private exams in hallways, so things get missed," he says. "It’s just an immoral standard of care, really.”

A lack of long-term care beds, rolling closures at many emergency departments, and overcrowding at others, demonstrate key challenges of health care delivery in rural Nova Scotia. And the challenges have escalated in recent years, leading many Nova Scotians to say the health system is in "crisis."

Their grievances are voiced in online advocacy groups, where stories of frustration with the system are intermingled with practical updates on hospital closures, where to seek alternate care and plans for protests.

In the U.S., Democratic presidential candidates Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren want to provide universal health coverage for all Americans and essentially abolish private insurance plans in the process. Sanders is fond of citing Canada as a source of inspiration — a country where, practically speaking, private insurance is not an option for the majority of medical services.

Canada spends much less of its gross domestic product on health care than the U.S. does; there are zero out-of-pocket payments for patients, even for complex surgeries or lengthy hospital stays; and Canadians are overwhelmingly proud and supportive of their system.

But in Nova Scotia, there are struggles to fulfill the promise of "reasonable access" to services outlined in the Canada Health Act.

No Risk Of Bankruptcy

Lucy MacNeil is a food service manager in a nursing home, with nothing but gratitude for the treatment she received after a diagnosis of advanced breast cancer in 2018.

“It metastasized to the bone and I was taken care of lickety-split,” MacNeil says. “When you're really sick, they don't waste any time with you at all. So I have absolutely no worries for financial aspects, as far as my actual care goes.”

Yet MacNeil, who is at risk for potentially life-threatening fevers due to radiation treatment, still says the health system is in "crisis."

"If my fever is up longer than an hour, I have to get my butt over to emergency," she says. But the ER in her seaside town of Shelburne is often closed due to under-staffing, and there often aren’t enough ambulances to go around. This means someone like MacNeil could wait 45 minutes while an ambulance comes from a neighboring community where the ER is open.

"When you're really sick, they don't waste any time with you at all. So I have absolutely no worries for financial aspects as far as my actual care goes.”

Lucy MacNeil

Karen Mattatall, the mayor of Shelburne, near Nova Scotia’s windswept southeastern tip, notes that ambulances are run by private companies with government contracts and cost most patients hundreds of dollars per ride.

She adds Shelburne's hospital, Roseway, was a full-service facility in the '90s, but has since cut back significantly on services.

"Basic things — blood tests, X-rays — [it's] very difficult to even have those things done in this community," Mattatall says.

"But they'll tell you, 'Well, you know, the population decreased in the county and therefore, we couldn't continue to have those services.' However, there's still 15,000 people living in this county that deserve to have access to services and deserve to have them in a reasonable, appropriate time. We live in Canada. That's a guarantee with the Canada Health Act ... universality and accessibility."

Cumulatively, Roseway Hospital’s ER was closed for at least 14 days in October and November, according to a WBUR review.

That same WBUR review found that, of the 37 emergency departments scattered around Nova Scotia, 16 experienced rolling closures during this time — adding up to thousands of hours of closures.

Concerns About Access To Doctors

Lucy MacNeil in Shelburne is like most Nova Scotians in that she has access to a family doctor – what those in the U.S. would call a primary care physician. She says she visits her doctor every three months to monitor her health.

Yet, 13% of Nova Scotians age 12 and older do not have access to a family doctor, according to government data released this year; and that number is lower than the Canadian average of 15.3%. For comparison, Massachusetts and Maine have among the lowest rates — about 13% — of Americans who do not have a primary care doctor. (The average in the U.S. is 22.5%.)

Experts and advocates say this lack of access to family physicians is one of the main contributing factors to Nova Scotia's health care system woes.

“Because there is no continuity of care, or very little of it, the problems magnify in terms of people’s life struggles, whether it’s the beginnings of a disease, or a chronic problem that you’ve had for a while," says Tony Kelly of the Digby Area Health Coalition. The group advocates for better access to doctors in and around Digby, a fishing port town on the Bay of Fundy.

Without a family doctor, a person with a chronic condition like diabetes must go to an ER or walk-in clinic for insulin and a checkup. Cancerous tumors can go undiagnosed with no regular checkups. This problem also results in long lines at the ER, where Nova Scotians may go for something as simple as filling a prescription.

Peter Armstrong, 66, grew up in Digby and recently moved back to the area. Armstrong says he had a heart attack in 2015. When he came back to Digby, he called up a registry to get a primary care doctor. He was put on a list.

“I haven’t heard from ‘em yet,” he says. “It’s been over two years.” Other patients, doctors and health care experts told WBUR this wait time wasn't uncommon. However, it's worth noting that the provincial government's wait list system has only been in place since November 2016.

A year ago, Armstrong worried he might be experiencing symptoms of another heart attack. He said his only option was to go to a walk-in clinic.

And he says the hospital in Digby is regularly crowded with people seeking prescriptions and other primary care.

“People will go in there at 8 o'clock in the morning, and they’ll stay there until 4 or 5 in the afternoon and still possibly not see anybody,” he says. “In a town that used to have 10 doctors that I could name, that’s unacceptable.”

Health care delivery is a growing problem in many low-density locations. In the U.S., rural hospitals are struggling as well. The U.S.-based National Rural Health Association warns that sustained cuts to Medicare "threaten the financial viability of more than one-third of rural hospitals" in America.

Dr. Gary Ernest is a family physician in Liverpool, an Atlantic coastal community. Ernest is the president of Doctors Nova Scotia, a subset of Canada’s nationwide doctors association.

He says he worries patients will just give up the search for a doctor entirely.

"People ... will decide, you know, 'I don't have a family doctor. I don't want to go and wait for four, six, eight hours, in an emergency department or more; I'll just take my chances,' " he says. "And what ends up happening then is problems that could have been dealt with in a straightforward way — if they were caught early — become major issues."

Canadian federal law guarantees "reasonable access to health services" for all Canadians. But the law leaves it up to the provinces to design and deliver health care, which makes for inevitable imbalances in services and physician compensation. In Nova Scotia, doctors have been paid the least of any province in recent years.

That, and, according to Ernest and others, a contentious relationship between doctors and the body in charge of overseeing the provincial health care system — the Nova Scotia Health Authority — contributed to doctors leaving to work elsewhere.

"... Problems that could have been dealt with in a straightforward way -- if they were caught early -- become major issues."

Dr. Gary Ernest

Last week, however, a new contract between doctors and the provincial government was reached that will bump physician pay in Nova Scotia to the highest of the four Atlantic provinces, according to a statement from Doctors Nova Scotia.

The announcement has been met with measured skepticism by some doctors and activists who say the health authority has too many layers of bureaucracy and has a history of not respecting the wishes or needs of doctors.

The Nova Scotia Health Authority denied WBUR's request for an interview and did not respond to a request for comment.

Ernest, however, is cautiously optimistic.

"The Nova Scotia Health Care Authority has really taken steps to try and reverse the attitudes that existed before," Ernest says, citing changes to senior management and its board of directors.

As Canadian System Evolves, Candidates Explore Single Payer

In Nova Scotia, as in most of Canada, doctors who opt into the public insurance system are barred from accepting private payment for the same services. For example, if you opt into the government system as a doctor, you can’t legally perform a knee surgery or similarly "medically necessary" service in Nova Scotia for cash or private reimbursement of any kind.

The "Medicare for All" plans that Sanders and Warren are pushing for in the U.S. would similarly phase out private insurance options — barring employers from offering separate plans that would compete with Medicare.

In Canada, medically “unnecessary” procedures, like plastic surgery, are not covered by the public insurance system. But neither are prescription medications, dental or eye care. All of these treatments are only covered by private insurance plans. In fact, it’s estimated that 30% of Canadian health care spending is paid for through private insurance.

Sanders and Warren promise total coverage for prescription drugs, dental and eye care as part of their health care plans.

The bulk of medical services in Canada — 70% of overall health care spending — are funded through taxes. There's a 15% sales tax on most goods and services, from home sales to e-books, to gasoline, snacks and soda. Most Canadians also pay higher income taxes than Americans do.

Bill Hsiao, an economics professor at Harvard University, recently conducted studies looking at health care delivery in Canada, Germany and Taiwan.

He says universal medicare is clearly the most efficient way to set up a health care system; and the U.S. system is clearly in a league of its own when it comes to health care spending.

“About 20% of every dollar we spend [is] for administrative expenses — spent by insurance companies and by providers who have to respond to the rules and procedures imposed on them by numerous insurers,” he says. “Under single payer, you only have one set of rules.”

Canada spends over 10% of its GDP on health care, compared with about 17% for the U.S. Of the 36 countries belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the average is roughly 9%.

But, Hsiao says that Canada is now "under-funding its health care."

“Canada had an excellent system that was a role model for the world, since the late 1970s until the late 1990s," he says.

Then Canada went through a prolonged period of recession. During that time, Canada shifted the burden of health care spending onto the provinces.

“That's what's causing some of the shortages of physicians, as well as the long waiting lines for non-emergency medical cases,” Hsiao says.

Many of the folks WBUR spoke with in Nova Scotia seemed nonplussed when asked if the U.S. would be wise to implement a Canadian-style health care system.

"I find it interesting that Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders look at us as a model," says Dr. Robert Miller, one of the surgeons coping with overcrowding at an ER in Kentville, Nova Scotia. "There are much better models internationally. We can all look up this data and see who's doing a good job and who's not. And Canada's not."

Back in the U.S., John McDonough, a Harvard public health professor who worked on President Obama's Affordable Care Act, believes that Medicare for All is the smartest way to set up a system, but thinks it isn't politically feasible right now.

"There are other feasible systems [besides single payer] — particularly Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland — that do it another way but achieve universal coverage, have significantly lower costs than the United States, and have high rates of public satisfaction," he says. "That could be achieved [in the U.S.] without doing what happens when we go for the whole thing, which is burning down the house.”

This segment aired on December 3, 2019. The audio for this segment is not available.