Advertisement

Researchers May Have Found The Roadmap To An HIV Vaccine

Former U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler said that an AIDS vaccine would be ready for testing in two years.

That was in 1984. Scientists have been failing to create an effective HIV vaccine ever since.

But perhaps not for too much longer. Researchers at Harvard Medical School and Duke University published results in the journal Science on Thursday outlining a new strategy that might lead to an HIV vaccine.

One reason a vaccine has been so elusive is that HIV evolves rapidly, making it difficult for immunologists to target.

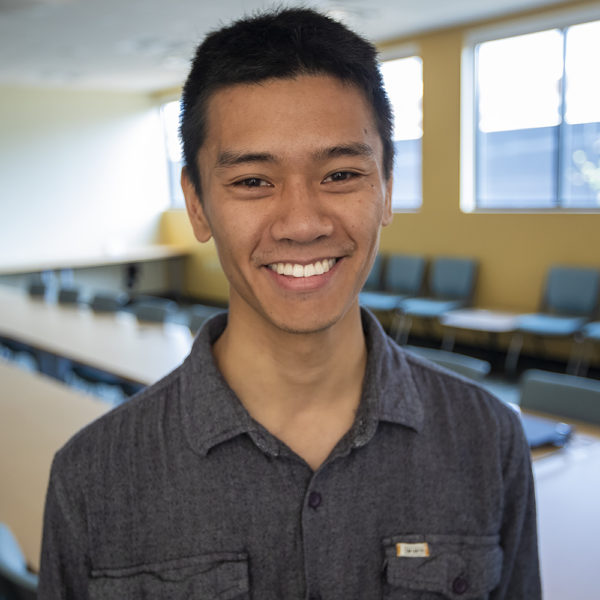

“Even within a person, the virus mutates and changes over time. So, the virus on the first day of infection looks different from the virus 10 years later," said Kevin Saunders, an immunologist at Duke University and a lead author on the paper. "The virus can evolve and evade the antibodies while you're still trying to generate them.”

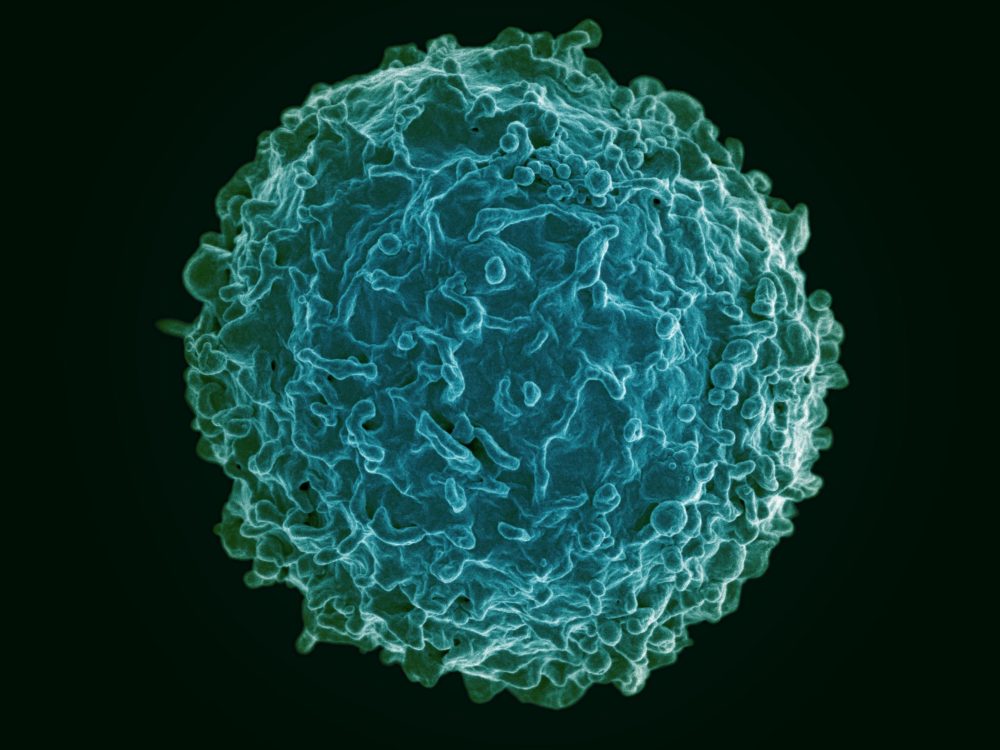

But a subset of antibodies does have the ability to recognize these different forms of HIV, Saunders said. They're just rare and difficult to generate with a vaccine.

In their paper, Saunders and his colleagues described a prototype vaccine that works like an instruction manual for these defense compounds. Using different components, the vaccine guides the immune system to develop antibodies that have all the key features needed to be effective against HIV.

The approach showed promise when Saunders tested the vaccine in mice and monkeys, he said. It’s not complete, but “it’s a step forward in trying to make an effective HIV vaccine,” he said.

We spoke with Saunders about this research. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What’s special about these antibodies, and what makes them so difficult to make?

There are a lot of different versions of HIV out there circulating in the global population. These antibodies can recognize HIV with slightly different shapes, bind to those viruses and neutralize them.

But there are a few reasons why it’s taking so long to make a vaccine that can generate them. Antibodies develop over time, and these highly potent HIV antibodies need to acquire key features during their development. If the antibody doesn’t acquire them, then they don’t develop this broad reactivity to HIV, but those features are not usually made by your immune system.

The other problem is the actual precursor for the antibodies are rare, so you can only make so much of them. You need a vaccine that can target those rare precursors, activate them, and allow them to expand in number and undergo evolution to become that better HIV antibody.

Eventually, we hope that this will be a preventative vaccine.

What happened once you started testing it?

We vaccinated mice and monkeys to see if they would start generating antibodies with the specific features we are trying to get. First we saw that we were getting the right mutations in the antibodies, and then we tested to show that they were functionally equivalent to the type of antibodies we wanted. These only have the first couple of key features you need. There are other key features you need, so the vaccine isn’t complete.

But it is definitely exciting because it suggests we’re on the right path. This tells us the strategy we can try to use to complete the vaccine. And it’s definitely exciting to know that we can vaccinate and overcome these key features as a road block.

How is this different from the way vaccines are usually made?

HIV has been different from what vaccinologists have had to do. For many vaccines, you just need to know what components of the pathogen are that antibodies can develop against. Then you take that component, vaccinate people and make antibodies with protection. But with HIV, we had to understand the unusual features of antibodies that work against HIV, and why they don’t show up when we vaccinate. It was many years of studying HIV-infected individuals, vaccines and antibodies themselves at the molecular level. Now we’re translating that into vaccine design, and it’s a different approach to what’s had to happen in the past.

What needs to happen next before you have a working HIV vaccine?

This paper is a proof of concept that just shows we can do this. We’ve only done it for the initial stages, but it shows we can do it. Now we just need to complete the job by finding additional vaccine components that can select for the remaining key antibody features. We believe this is the way to make an effective, protective HIV vaccine. But of course, we can’t guarantee that until we’ve made it and tested it and we know the results.