Advertisement

Inside A Boston OR, Surgery Shows Hospital's Steps To Reduce Its Carbon Footprint

Resume

At 8:30 on a Wednesday morning, nurses roll 83-year-old Rev. Ralph Kee into a place with one of the largest carbon footprints in Boston: a hospital operating room. He comes to a stop in the middle of a room filled with monitors, movable lights and tables covered in blue cloth.

The health care sector produces 10% of all greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. Hospitals are 36% of that. And operating rooms are their hot spots for emissions, waste and energy use.

But this OR, inside a renovated area at Boston Medical Center (BMC), is about as climate friendly as they come. BMC says the renovation has helped it draw 70% less energy from the grid, starting in 2012.

Kee is here because doctors discovered that his left carotid artery is blocked, putting him at risk for a stroke. As he prepares for surgery to remove the blockage, Kee says he's pleased to learn about steps BMC is taking to reduce the hospital's carbon footprint.

"That’s important for Boston itself," he says. "Talk about climate change — we’re right in the middle of it."

So Kee has agreed to let us watch all the things nurses and doctors do differently here to reduce the impact his surgery will have on the planet.

Kee's encounter with health care and climate change begins with the plastic mask an anesthesiologist lowers over his nose and mouth. Kee inhales sevoflurane. In many operating rooms across the country, the gas going into Kee’s lungs would be desflurane. But BMC rarely uses it anymore.

"Desflurane has a higher carbon footprint," says Dr. Mauricio Gonzalez, BMC's vice chair for clinical affairs. "It’s a bigger greenhouse gas than the other anesthetics."

Desflurane is so carbon intensive that giving it to Kee for this two-hour surgery would be like driving 756 miles as compared to 16 miles with an equivalent dose of sevoflurane. And at BMC, the CO2 Kee exhales will be captured inside a canister system the hospital began using in 2018. The carbon is absorbed in pellets that Gonzalez says are safe to throw away.

"The whole focus on the environmental impact of operating rooms and anesthesia, it’s a relatively new thing," Gonzalez says. "Yes, we’re responsible for the patient on the table, but in the end we’re all responsible for the planet we live in."

That attention to the planet unfolds during Kee's surgery in two more ways: lower energy use and less waste. If you’ve been inside a hospital lately, you know there’s a lot of waste.

"Anything that rips goes in there," says nurse Polly Woodworth, one of BMC's most vigilant recyclers, as she tosses the back of a sterile tubing package into a large green trash bag.

Woodworth bounces between four receptacles: green for recycling, red for bloody trash. There's a blue bag for laundry, and a clear bag for clean trash.

Sometimes deciding what goes where is just too much in an already high-stress environment. Woodworth watches one of the surgeons toss a large piece of molded plastic into the clean trash bin. She moves it to recycling.

"I’m a trash picker," Woodworth says, giggling. "I can’t help myself."

BMC recycles about 38% of what would otherwise be trash. And today the trash bag fills about twice as fast as its green bag neighbor. To understand why, let’s get back to the operating table where Kee is out.

Surgeon Doug Jones looks for ways to prop up Kee's left shoulder and create better access to his neck. He can't get the right angle and calls for a blanket or towel. A dozen towels sit on a table about 10 feet away. All arrived in this OR wrapped in a sterile polypropylene fabric often called "blue wrap." BMC can't find anyone who will recycle it so the hospital tosses 13 tons a year.

David Maffeo, BMC's senior director of support services, is working on a partial solution: turning those sheets of blue wrap into BMC tote bags.

With Kee's neck and left collarbone exposed, Jones begins searching for the carotid artery. It's deeper than expected, but Jones finds this major vessel that delivers blood to Kee's brain, punctures it and clamps one end. He and colleagues begin threading a wire through the plaque build up, singing along to his R&B playlist.

One reason operating rooms are such energy epicenters: ventilation. BMC says the air in this room is sucked out and replaced for purity 20 times an hour as compared to six times an hour in the hospital room where Kee will spend the night.

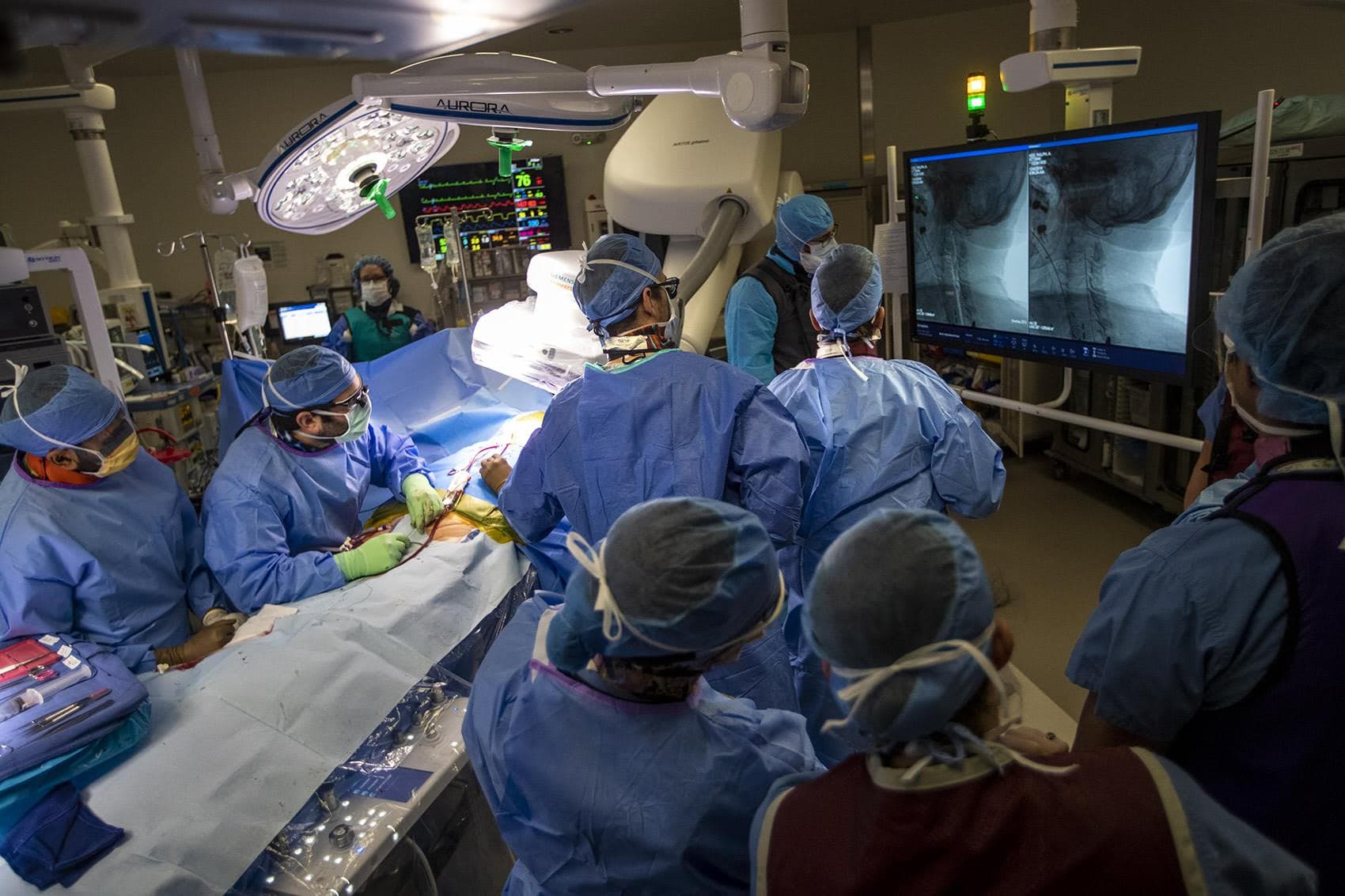

And this operating room consumes even more power than most. It's a hybrid mix of imaging and surgery. About halfway through the procedure, surgeons roll a high-tech x-ray machine over Kee. It will take still and moving pictures so Jones and colleagues can see the stent they snake through Kee's artery to avoid cutting open his neck.

As the x-ray images of Kee's skull and collarbone appear on two large screens, Jones asks someone to dim the room's 40 lights. BMC has converted all hospital lighting to LED bulbs, which are between 50-80% more efficient, and it has installed sensors that turn off lights in any unoccupied hallway or room.

As the stent moves into place, Jones asks a colleague to confirm that the artery is stable. He adds stitches and flushes some blood out of the area.

Operating rooms are colder than the rest of the hospital. Keeping the room temperature around Kee at 65 degrees is no easy feat with the heat from a dozen bodies, lots of lights and machinery. BMC uses what’s called a free cooling system. In the winter, outside air chills water that cools this OR. The hospital is warmed in part by the heat thrown off a co-generation plant installed three years ago. That plant could keep the hospital running, in a more limited capacity, if the power goes out during a storm.

"The sheath looks good, right?" Jones asks the surgical team. "Alright, carotid’s clamped."

In a few minutes, Jones is done. X-ray images of Kee’s neck, before and after the surgery, are still on the screen. Two hours ago his left carotid artery was almost completely blocked.

"There was just a whisper of blood getting through," Jones says, pointing to the "before" picture of Kee's carotid artery. "Now you can see it’s normal."

BMC aims to make similar repairs to an ailing planet. Senior Vice President of Facilities Bob Biggio is one of the masterminds behind the hospital’s climate focused renovations.

"When we launched our campus redesign plan, it seemed only natural that trying to create a healthy environment for our patients is one of the places you'd start with trying to keep your patients healthy," Biggio says.

Health Care Without Harm, a global organization working to address climate change, calls Boston Medical Center a national leader among hospitals when it comes to the issue. Sarah Spengeman, the group's associate director for communications in the climate and health program, mentions BMC's rooftop garden, the hospital's ability to stay open during a power outage and its commitment to green energy.

"The cool thing about Boston Medical Center," says Spengeman, "is that they're doing it all, they're doing it well and they're really integrating it into their core mission of being a safety net hospital."

BMC aims to be carbon neutral next year. It would be the first Massachusetts hospital to do so. Meeting that target is proving to be more difficult than planners imagined. BMC offsets carbon produced here with renewable energy credits from solar power purchased in North Carolina. But as the grid gets greener overall, the value of those credits is dropping.

By mid-afternoon, Ralph Kee is sitting up in bed, eating orange Jell-O and applesauce.

"I was pleased and almost surprised that I could start eating already," Kee says. "So I must be doing pretty good. Praise God for that, and the people that did it."

Kee will get a full meal soon. Anything he doesn’t eat will be dumped into the hospital’s biodigester, which turns four tons of food waste into water every month. BMC has spent more than $400 million on all these changes. They haven’t paid for themselves yet, but Biggio says they will.

This segment aired on December 18, 2019.