Advertisement

Harvard Astronomers Update Map Of The Milky Way Galaxy

A new discovery by Harvard astronomers shows the map of the Milky Way galaxy doesn't look the way we thought.

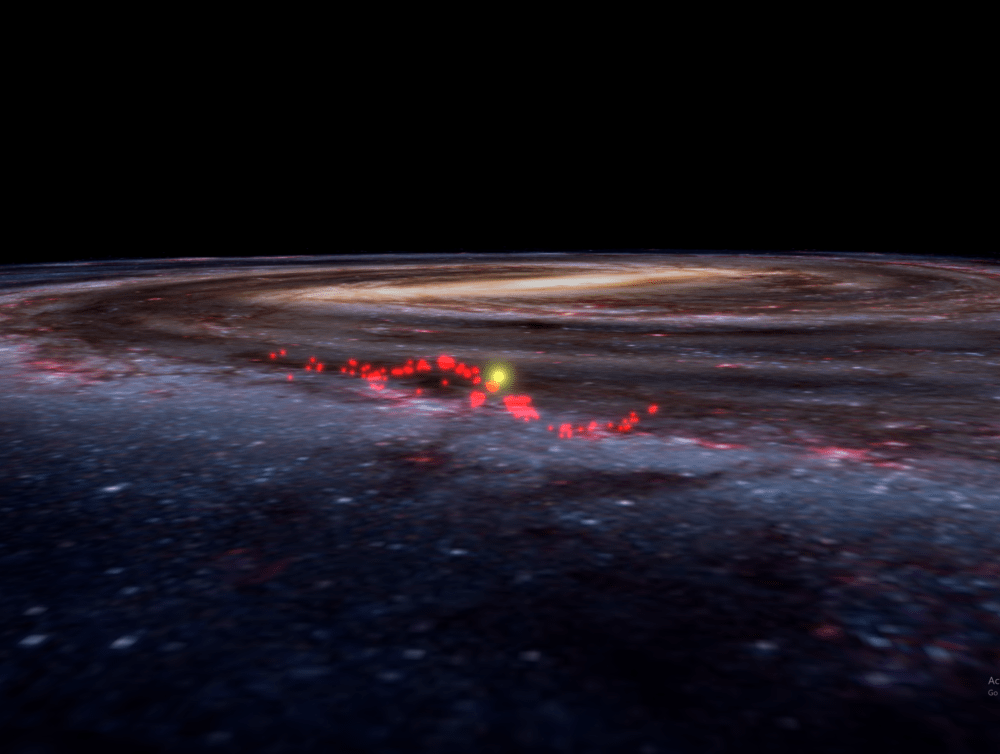

The paper, published today in Nature, reveals the discovery of the largest continuous gas structure known in the galaxy: a massive, wave-shaped gas structure extending for trillions of miles and about 9,000 light-years long.

The monolithic structure, called the "Radcliffe Wave," redefines past models of the galaxy. It looks like an oscillating wave when viewed "sideways" from the Earth but appears straight when observed from above, leading scientists to realize that the Radcliffe Wave actually forms the previously-described "Local Arm of the Milky Way".

"So we kind of redefined what the local neighborhood of the sun looks like in the galaxy," explained Applied Astronomy Professor Alyssa Goodman, one of the authors of the study.

Goodman, who also serves as co-director of Harvard's Radcliffe Institute science program, said scientists were originally hoping to precisely measure the distances between gas clouds in the Milky Way when they noticed something they weren't expecting.

"When we got these super-accurate distances, pictures sprung into view that we just could not believe," said Goodman. "All of these clouds that we knew were somewhere vaguely in the vicinity of the sun in the Milky Way fit into a sine wave, as if you were kind of holding a rope and making it go up and down."

The wave's existence disproves prior notions about gas clouds in the Milky Way that have persisted for more than 100 years.

Researchers expected the clouds they measured to be arranged in a partial ring around the sun called "Gould's Belt," after the scientist who first described the cluster of stars in the late 1800s. But Goodman says the depiction of a "belt" of stars surrounding the sun was based on imprecise measurements that included too much error.

Once scientists reduced the uncertainties in the distance measurements between the gas clouds, she said, "everything just snaps into a clear view."

Goodman also suggests the Radcliffe Wave and the sun have a close relationship that may go back billions of years.

Advertisement

"The sun's orbit crosses the orbit of the Radcliffe Wave in the Milky Way in such a way that the sun may have actually been formed at one time in the gas where that is now," Goodman said. "We don't really know that for sure, but we know that 13 million years ago, which is a very small amount of time in that 3-billion-year lifetime of the sun, the sun would have been crossing very, very close to this Radcliffe wave."

According to astronomers' projections, the sun may very well "surf" to the other side of the Radcliffe Wave again 13 million years from now.

In the meantime, it's time for scientists to re-think their three-dimensional models in the galaxy — and for us to update our "cosmic address."

"There was just this mishmash of information about where we really were in the Milky Way," Goodman says. "And these super-accurate distances make it clear. What does this mean for people? You know where you live now in the Milky Way."

This segment aired on January 9, 2020.