Advertisement

'Colored People Time' Confronts How Blacks Navigate Race Each Day

Resume

At MIT’s List Visual Arts Center there's an exhibition that turns time on its head.

The show, called "Colored People Time," dives into questions of race, colonization, and reparations. First shown at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, the exhibition now fills one long gallery in Cambridge.

Curator Meg Onli explores the daily experiences of black people. In particular, she’s very interested in language, and how black people use language to steer through inequality. She's curated pieces of art that are distinct, but that are also in conversation with one another.

“The objects range from 1899 to 2019,” Onli said as we walked through the exhibition. The show is premised on the idea that "future building is inherently tied to blackness." In the gallery notes, Onli delves into the origins of the title, which is meant to be a kind of reclamation. That CPT or "Colored People Time" can exist outside the western concept of what it means to be on time.

She also uses the framework of time — in reverse — curating three spaces: future, present, and past. Each of the areas is sparse, with maybe four to six pieces, and the concepts are dense. One of the pieces in the first section is by artist Martine Syms.

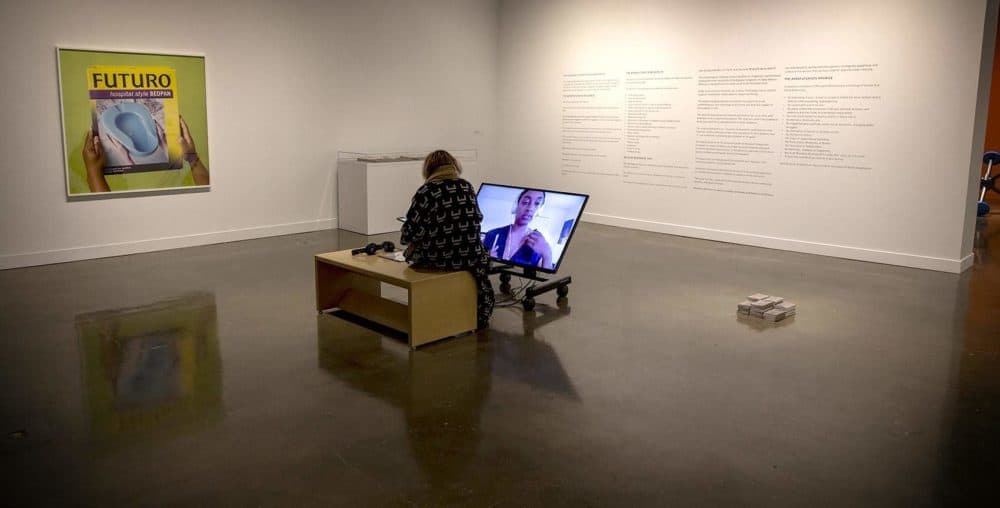

It's called “The Mundane AfroFuturist Manifesto.” Afrofuturism is described as a genre where African diaspora and aesthetic culture intersects with technology, where space explorers find new Afrocentric mythical worlds like Wakanda in Black Panther.

Sym's manifesto critiques the stereotypes contained in Afrofuturism.

“She points out that, you know, out of 534 space travelers, only 15 have been black,” Onli said. “The likelihood of us escaping to another planet is highly unlikely. And she sort of ends by saying, the most likely future we have is ourselves and our planet. So what are we going to do with it? And so that piece really shapes a lot of the exhibition.”

Syms, the artist, calls out “afrofuturism” for its tropes and escapism. It means there is no place, no utopia even imaginary that people of color will not deal with the oppression of white supremacy. So she posits perhaps that’s an opportunity to build a better future here on Earth.

“So I'm not going to necessarily fantasize as if I'm going to escape,” Onli said. "It's what am I going to do with the mess that I've been given? And I think a lot of my practice really stems from that. It's why I work in museums to begin with.”

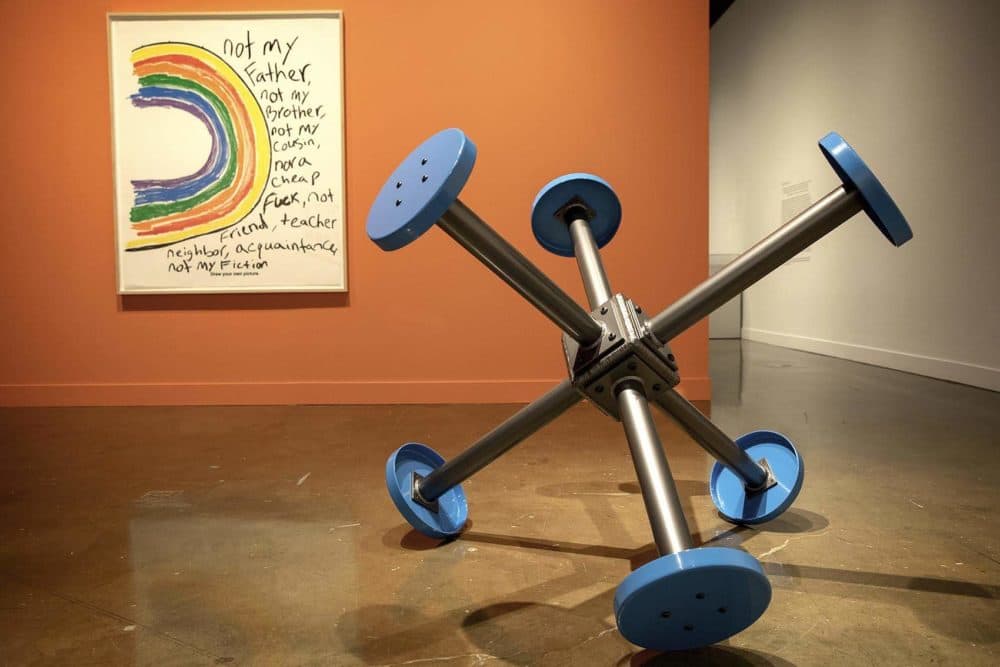

From there we walk into the present. There are splashes of orange on a wall, which is a direct reference to the prison jumpsuit.

Sable Elyse Smith’s “Coloring Book 33,” hangs nearby. This screen-printed work draws inspiration from the coloring books often given to kids to teach them about the prison system when they visit loved ones who are incarcerated.

Yet on it is a sideways rainbow and the words, “not my father, not my brother, not my cousin, nor a cheap f---, not friend, teacher, neighbor, acquaintance, not my fiction.” Smith also created a sculpture she calls “Pivot,” which is made from the same materials used to make prison visitation benches.

“A lot of the pieces in this space in one way or another are having conversations around reparations,” Onli said.

She points out a specific piece in that gallery called “Depreciation.” Artist Cameron Rowland purchased land on South Edisto Island in South Carolina where the concept of “40 acres and a mule” was originally decreed. This was a part of the reparations slaves were promised following the Civil War in 1865, an order that was never actually implemented. This land was returned to white Southerners and the former slaves were given three choices, Onli said. Work for the remaining plantations, leave the area, or get arrested and placed into convict leasing. She calls this the start of the modern day prison industrial complex.

Rowland, the artist, purchased land here and created 8060 Maxie Road, Inc. Through a restrictive land covenant, Rowland shows the land assessment documents and makes it so that no commercial or residential property can be built here. This process renders the land useless as a commentary on the notion of property.

Finally, Onli takes us into the past, into a section with 3D-printed ceramic sculptures based on the Penn Museum’s African Collection. She worked with anthropologist Monique Scott and artist Matthew Angelo Harrison who photographed, scanned, and created these copies.

“All the pieces have been distorted,” she said. “So none of these are a one for one. All of them have been manipulated in different ways, be it their size. Some of them are being morphed into each other.”

The point is to comment on the idea of what we give value to, how these objects circulate and the tension between what is precious and what isn’t. Ultimately, what "Colored People Time" tries to accomplish is a collective refusal, Onli explained. “A refusal to disavow our embodied sense of time, beyond capital’s demands. A refusal to accept that history occurs, and remains, in the past. A refusal to adhere to Western time as the only time,” she said.

"It is very theory driven,” she said. “It's definitely approaching people to say, like race is incredibly complicated and we have to really like dig into this. But I'm sort of coming from a default that like as people of color, we have a really sophisticated understanding of theory, race, performativity, all of these things. And there's a way that you can kind of do a show like Colored People Time. That is, I wouldn't say a wink and a nod, but it definitely is saying like, hey, this shows for you."

"Colored People Time" is on view at MIT's List Visual Arts Center through early April.

This segment aired on February 17, 2020.