Advertisement

'Crisis Schooling': Educators, Families Balance Learning And Wellbeing Amid Closures

For Elisabeth Preis, it’s easy to describe life at home with her three kids during the school shut down. “In a word, pandemonium,” she said. “It’s just so incredibly chaotic.”

Preis is a recently widowed single parent from Brookline. She says every day is a balancing act as she tries to keep her career afloat while attempting to keep her two older kids on track with their school work and tend to a two year old.

While Preis is glad that her kids’ teachers are hosting class Zoom meetings twice a week and sending out assignments, it's a lot for her to keep up with. Her 10-year-old is very prone to distractions on the computer unless she's sitting there with her keeping her on task.

“It's very hard to kind of have that level of vigilance when the first grader also needs help with whatever she's doing,” said Preis. “And, you know, the toddler's running around throwing food all over the floor.”

Preis has made peace with the fact that this is not going to be an academically productive year for her kids. In the last twelve months, her kids lives have been disrupted so much from the death of their father to this extended school closure. Her priority now is to just make it through 2020.

“I'm giving myself and my peers and the teachers and everybody kind of a big pass, because this is also an incredibly fraught time for everyone,” she said. “If they can just get through this and be OK and as emotionally unscathed as possible then that’s great.”

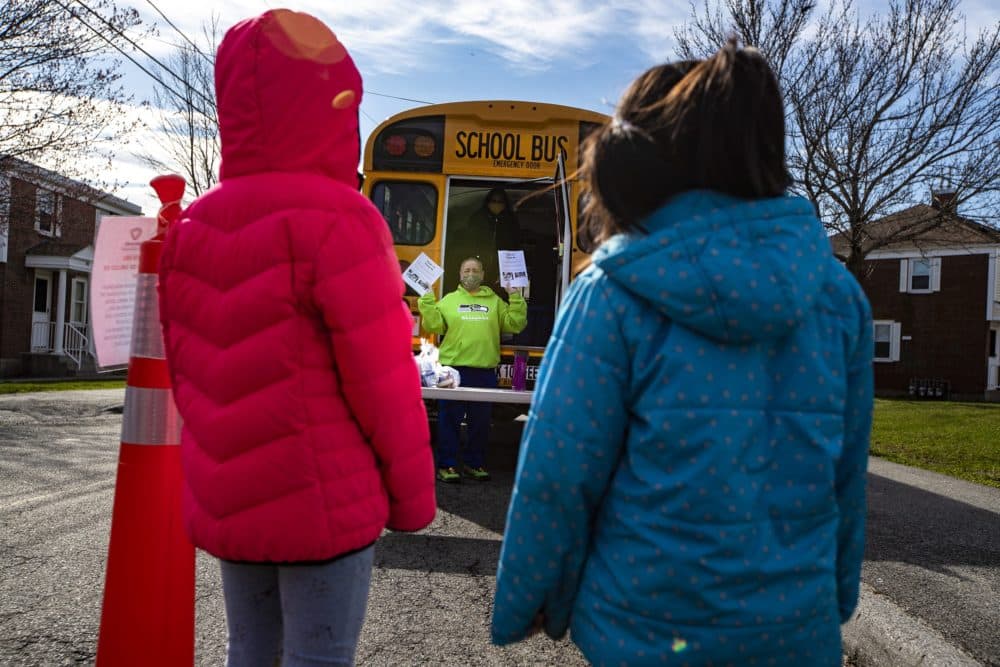

During the pandemic, parents like Pries are prioritizing emotional well-being over school work. For most Massachusetts schools, meeting kids' social and emotional needs is also a top priority. Many are under enormous stress to serve all of the needs of their community, from rigorous academic material, to mental health support and a source for food. And they're doing this all while faced with the new reality that schools across the state will be closed for the rest of the year.

In an effort to get an accurate picture of what kids needs are right now, a lot of schools are doubling down of efforts to connect with each of their students. In the Haverhill Public Schools Superintendent Margaret Marotta is challenging her teachers to have a conversation, preferably a video conference, with each of the school system's roughly 8,000 students at least twice a week.

Advertisement

"This stress is is really impacting a lot of people," said Marotta. "So we want to make sure that our kids are safe at home when nobody [from school] has eyes on them."

Marotta is concerned about a host of issues like making sure kids with sick parents know what to do if their COVID-19 symptoms get worse to making sure kids aren't facing abuse at home and ensuring that none of the district students go hungry. While these concerns exist during "normal" times, the restrictions on physical contact has made meeting those needs much harder.

But despite the challenge, Marotta said she and her staff believe it's important not to lose sight of the school system's primary responsibility: education. While the student and family needs are urgent, a lot of educators and school leaders in the state believe that learning must continue.

"It's a basic social compact we have with families,"said Marotta. "We owe them an education."

State education officials are planning to release additional guidance this week about how to continue that education, now that schools have launched emergency remote learning in some fashion.

"As we've said before, closing the actual school buildings for the year does not mean it's time to start summer vacation early," said Gov. Charlie Baker Tuesday, as he announced students would not be returning to the classroom for the rest of the school year.

This pandemic and the resulting school closures is causing a lot of trauma for a wide range of students. And that's why the primary goal is to meet students where they are and plot a way forward for learning.

"Academic learning and cognitive functioning is not independent of emotional and psychological health," said Archana Basu, a psychiatry instructor and researcher at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Basu considers this remote teaching that families and districts are attempting right now as less "home schooling" and more "crisis schooling."

"We just need to acknowledge that there are these losses and stressors that can impact learning just at a cognitive level," she explained.

Even if it's challenging to learn while facing stress and loss, doesn't mean it's not worthwhile to attempt to continue learning. In some ways, having lessons available could help a student's emotional wellbeing. School work can provide routine and structure. It can also be a means of distraction from day to day stressors at home.

"It's not an either or situation," she said.

She adds that for some kids and families, not being able to progress academically is a stressor on its own, especially for older students who are close to graduation and will soon be competing for college seats or a place in the job market.

That's a huge concern for Chimere Almanzar, a mother of four kids in Roxbury, three of whom go to Boston Public Schools. Her oldest son is 18 and a junior at the Henderson Inclusion School. She's concerned that if the district backed off on its efforts to continue instruction, he'd miss out on the skills he needs to enter the job market next year.

"My focus is to make sure my kids are doing what they have to do. So when school starts back up they're not behind," said Almanzar.

Almanzar has been pleased with Boston Public Schools' efforts to provide academic material. It's not perfect, but for her it's better than a total cancellation of classes and classwork.

It's a basic social compact we have with families. We owe them an education.

Superintendent Margaret Marotta, Haverhill Public Schools

But for other Massachusetts parents, efforts to continue learning don't go far enough. A group of parents in Newton recently posted a petition to Change.org pushing for more "meaningful expectations" and "ongoing and measurable student learning."

David Goldstone, the petition's creator, argued that Newton Public Schools must not use the fact that remote learning is different from learning in a classroom as "an excuse for watering down school services to the minimum expectations permitted under state law or guidelines."

But Newton Superintendent David Fleishman said he's been receiving "a range of feedback."

"We're also getting student feedback, where students are saying, look, there's actually too much academic work," he said. "Some of our students are saying that, 'We don't want to be on a screen all day.'"

Fleishman notes that public school systems are legally obligated to offer every child in the community a "free and appropriate public education." Effectively serving students with certain special needs remotely has been particularly challenging for schools. And even in a community like Newton, where the median income is around $104,000 a year, there are still families who don't have access to an internet connected device.

"The challenge is: what about students who are not able to do it given their family circumstances right now, or they're not able to access the support that they need?" he said.

Still Fleishman believes offering academic work is important. And he's hoping that keeping students in a learning mode for as long as possible for the next two months will help make the transition back to in-person classes go a little more smoothly.

"We don't want young people to lose everything that we've done the first three quarters of this year," said William Hite, the superintendent of schools in Philadelphia, a city where about a quarter of the population is living in poverty.

Hite has taken a slower approach to pushing forward with academic work. For the last month, the school system has been offering students enrichment activities that aren't graded. The goal is to launch what he's calling "planned instruction" that will be graded in the first week of May.

In the meantime, the Philadelphia school system is working to get devices and internet access to students and helping teachers get proficient with the new learning platforms. Hite acknowledged that learning online is not ideal. Still, he said the district has to at least try to make these lessons as effective as possible.

"This is all new to many of us and we will only get better at it as as we do more of it," he said. "And it looks like, unfortunately, we're going to have that opportunity."

Just like Hite's team, superintendents and school leaders in Massachusetts are trying to make the most of this school year, even if access to instruction is undeniably uneven. Statewide data about how current efforts to distribute Chromebooks and put up WiFi hotspots in underserved areas has impacted student access is not yet available. But according to 2018 Census data, about 14,000 kids in Massachusetts under 18 didn't have access to a computer and roughly 49,000 did not have broadband service in their homes.

School leaders are also starting to shift their focus to next school year. There's a lot of research about how summer break impacts students, but what about this months long pandemic related closure? How will state schools get everyone back on the same level and pace of learning once they're all in the same room together again?

"I think one of the things we can expect is that there's going to be even more variation in where students are starting in a given grade heading into next school year than is typically the case," said Martin West, a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and a member of the Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education. "My hope at least is that we can find ways to support school districts in doing a really good job of diagnosing where students are and what they need in order to keep moving forward and not suffer long term consequences."

Educators are still making adjustments to continue academic learning for the next two months while also providing basic needs like food and counseling. Even with those tremendous needs, all agree that student learning is too important to just give up on. Even through its hard, most educators believe they have to at least try.