Advertisement

Remembering Great Scott, A Beloved Safe Haven For Boston’s Music Community

Residents of Boston were recently stunned by the surprising news that after 44 years, Allston music venue Great Scott will close permanently, via a statement made by general manager Tim Philbin on twitter, as reported by WBUR and others last Friday in an ongoing story.

Human beings are inclined to hold vigils — it’s an inherent part of our traditions — but sadly, in the age of COVID-19 quarantine restrictions, the Allston stronghold will be mourned by a community in isolation. As a musician and long time patron myself, the loss of Great Scott has brought on a great deal of reflection, and so, with the help of others also affected by its loss, we attempt to pay homage to a beloved institution.

I remember playing Great Scott for the first time in 2011. The 240-capacity room felt almost stately at first glance, but the checkered tile floor and dubious ceiling panels gave it an earnest grit, undoubtedly weathered from decades of use and abuse, but sturdy as an old warship. Much of the stage equipment had seemingly never been replaced, a few pieces likely inherited from touring bands who left gear behind. There was no green room, just a few stalls in the bathrooms, several of which didn’t lock. The sound, while always great, was usually just shy of ear-shattering. I’ve played that room a dozen times since then, and I remember each show uniquely. At times over the years, it felt hard to love, but the room always earned back its adoration by some sly magic emanating from its framework, the kind that turned weeknight gigs into sold-out shows, or shared cigarettes on the patio into lifelong bonds.

Captained by Tim Philbin for roughly 25 years, and later with help from talent-booker Carl Lavin, Great Scott underwent a gradual transformation from fratty college bar to a regional hub of emerging original music for local and touring bands alike. “Life in Allston was good,” Philbin wrote me in an email, recalling his first experiences at Great Scott as a doorman in 1987, eventually accepting an offer as general manager in the mid-1990s. But besting every wild night at work, Philbin’s strongest memory of the club was meeting his fiancé (they’re getting married in July).

“The stage is the perfect height from the floor. No one ever talks about that. Many stages are too high or too low,” says Ryan Walsh of Hallelujah the Hills, a band largely shaped by Great Scott for nearly 15 years. “Because Hills was born there, we always treated the place as our clubhouse. I shot three music videos there... Carl and Tim were always like, ‘sure, whatever.’ You approach some places with that idea and they start talking rental costs and such. Great Scott treated us like family.”

“I can’t say there was a single bad time,” says Carl Shane of Kal Marks, who, along with Hallelujah the Hills, played Great Scott 28 times.

Bryan Murphy of The Shills played 32 shows at the club over the last 15 years, the third most of any band in the establishment’s history. “Carl Lavin gave The Shills a shot to play Great Scott in 2005-ish,” he recalls. “It wasn't just a venue, it was a safe place for weirdos and an accepting community for everyone. Without it, there will be a giant hole that Allston will never be able to fill.”

...the room always earned back its adoration by some sly magic emanating from its framework, the kind that turned weeknight gigs into sold-out shows, or shared cigarettes on the patio into lifelong bonds.

Like many others, Sadie Dupuis of Speedy Ortiz found solace there on any given night. “When I moved two blocks from the club in 2014, I was there constantly drinking way too many chardonnays out of pint glasses — this was a venue staff kind enough to tolerate that nonsense logic,” she explains. “I could walk to Speedy's three-week, sold-out residency, at which we somehow did not repeat a single song, since we knew it was a lot of the same folks coming back to every show. Which was what Great Scott made you want to do — be there all the time.”

Buzz surrounded the establishment in 2016 when Consequence of Sound ranked Great Scott at No. 8 on their list of the “100 Greatest Music Venues in America,” a distinction spearheaded by music writer and former Boston resident Nina Corcoran. “I rang in several new years there,” she tells me in a message. “I've watched Ty Segall crowdsurf there. I once broke a guy's nose during a Pile set there… It honestly helped define my life living in Boston, and it definitely did the same for others.”

Dimitri Giannopoulos of Horse Jumper of Love recalls a Halloween show where the band performed as Oasis, cheekily performing “Wonderwall” twice during the night. “I remember as a band in high school, I thought if we could play Great Scott, it would mean we made it,” he says. Hip-hop artist Latrell James remembers the high caliber shows as a wide-eyed audience member long before he took the stage there himself. “The fans expect a good show when you hit the stage there and I’m truly going to miss those expectations,” he laments.

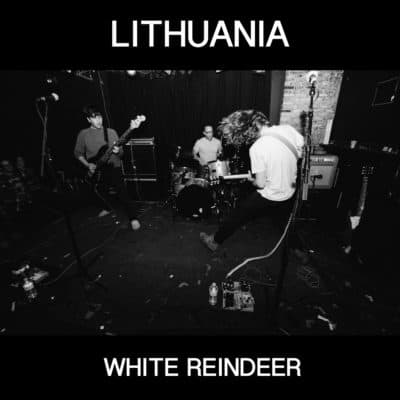

Though beloved and cherished by local Bostonians, the legacy of Great Scott transcends state lines. Even to passing transients, like Dr. Dog drummer Eric Slick, its charm was insurmountable. “It immediately reminded me of all of my favorite venues growing up in Philadelphia,” Slick says, recalling an early experience there in 2015. “My math/scuzz punk band Lithuania was ending a tour with Beach Slang and Worriers. Our friend Jason Cox took photos for us that night and one of the shots ended up being the cover of our album ‘White Reindeer.’ It just made sense. The place felt electric.”

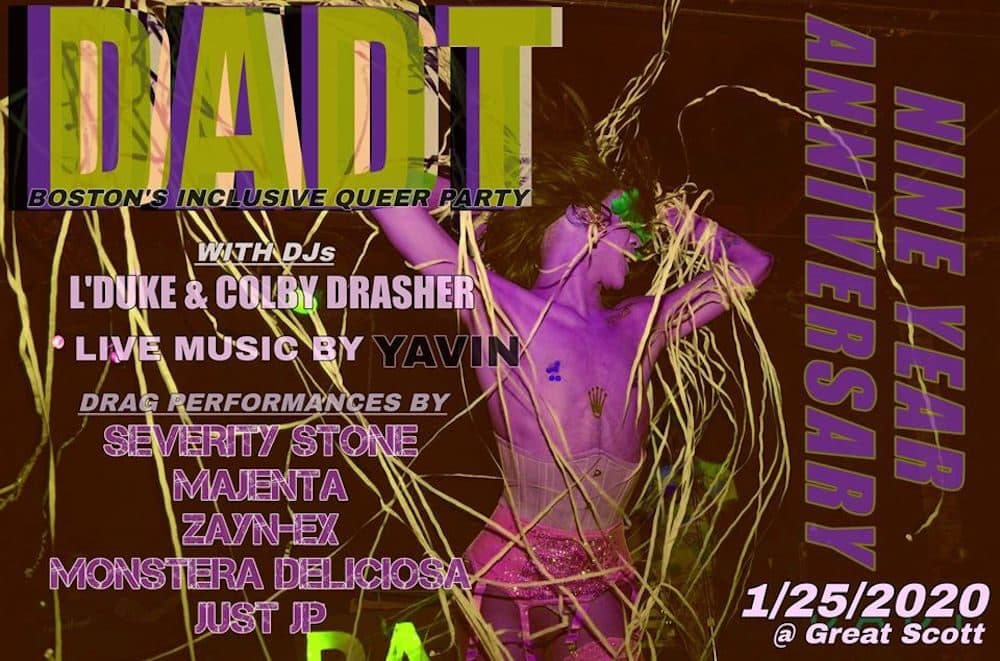

For nearly a decade, Great Scott was home to Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, a monthly queer dance party led by DJ Colby Drasher, an event organizer who felt greatly emboldened by the venue’s partnership, particularly in times of great tragedy. “After the Pulse nightclub shooting on June 12, 2016, the queer community was profoundly impacted... shortly after the massacre I hosted an event and took the opportunity to address the crowd. I asked everyone to take the hand of someone standing nearby, friend or stranger, and raise it up in solidarity. The entire packed club of over 200 people responded emotionally. It was a beautiful moment of warmth during a time when everyone felt vulnerable.”

Vanyaland editor-in-chief Michael Marotta recalls a similar bond to the venue from nights DJing events for The Pill, an indie dance party held every Friday night at Great Scott for roughly 10 years. “The music fueled the club night, and Great Scott was the vehicle for it,” he says. “Great Scott welcomed everyone, it was a beer-soaked safe haven and a refuge for so many people --the metalheads, the punks, the indie kids, the subcultures, the hipsters, the f--k-ups and rejects — and everyone was treated equal at Great Scott.”

The loss of Boston’s most beloved music venue hits hardest particularly with those most involved in its preservation, like musician Will Dailey, who in March raised $18,500 for non-salaried workers in Boston Venues, an effort inspired by his relationship with the club’s staff. “I did a streaming show to support the staff there at the onset of quarantine. That precipitated many more shows for many more clubs,” he explains. “This shuttering feels like a contagion of its own. One we can’t afford to allow to spread.”

"No final show, no goodbye party. We're all trying to have a wake for the place online, I guess, but is that really the closure we need?"

Ryan Walsh

“I know that the thing that makes bands, and clubs, and scenes special is that they are limited experiences,” Ryan Walsh adds, offering a message that radiates a familiar truth for all of us affected by its foreclosure. “All of these things have to end, or else, at a certain point, they stop being interesting. But I felt like Great Scott still had a lot of life left, and I find the closing sad and a shocker. No final show, no goodbye party. We're all trying to have a wake for the place online, I guess, but is that really the closure we need? I felt so comfortable there, found so much joy there, and am so grateful I was a part of the place's story.”

Though a petition to save the historic venue has begun circulating online, increasing rents and ongoing gentrification leave the future of Great Scott in limbo. And so, the music community loses another institution to a city undergoing rapid change, but it’s with fond reverence that the legacy of Great Scott will persevere in the memory of those who have been lucky enough to experience its greatness, every sweaty, drunken, bewildering, painful, fantastic memory from the heart of the checkered tile dance floor at 1222 Commonwealth Ave.