Advertisement

Review

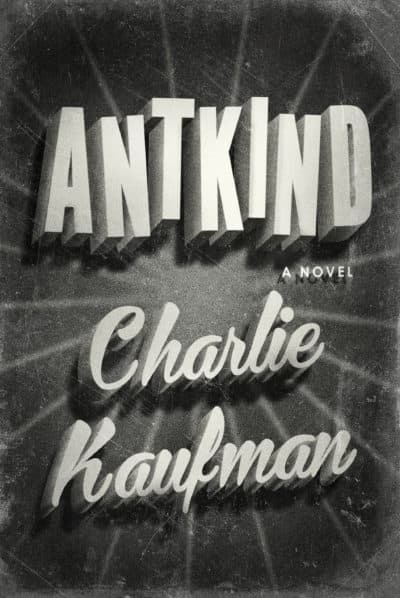

Charlie Kaufman's Debut Novel 'Antkind' Is Full Of Zingers And Petty Paybacks

When “Being John Malkovich” screenwriter Charlie Kaufman was hired to adapt Susan Orlean’s nonfiction bestseller “The Orchid Thief” into a movie, he was so stymied by the assignment that he turned in a script that was instead about a frustrated screenwriter named Charlie Kaufman who can’t figure out how to adapt Susan Orlean’s non-fiction bestseller “The Orchid Thief” into a movie. The result, 2002’s “Adaptation,” starred Nicolas Cage as both Charlie Kaufman and his (fictional) twin brother Donald, with Meryl Streep as Orlean and Brian Cox as screenwriting guru Robert McKee, whose advice radically restructures the movie into a Hollywood thriller while we’re watching it. It’s one of the funniest films ever made about the damnable process of writing and a brilliant hall of mirrors, with these fake versions of real people discovering emotional truths in phony circumstances.

After banging my head against the keyboard for a couple of days, I was half-tempted to turn in a review of “Antkind” — Kaufman’s massive, centuries-spanning, synopsis-averse debut novel — that was instead a piece about a frustrated film critic named Sean Burns who can’t figure out how to review “Antkind,” Kaufman’s massive, centuries-spanning, synopsis-averse debut novel. Except the wily Kaufman has already beat me to it. For you see, the 720-page book follows another frustrated film critic — this one named B. Rosenberger Rosenberg — to the end of civilization and beyond as he attempts to review a movie so enormous he can’t wrap his mind around it. Like most of Kaufman’s work, it’s about the slow suffocation of solipsism, and the impossibility of engaging with art — or anything else, for that matter — when you can’t get out of your own way. It’s also screamingly funny, with a laugh-out-loud zinger planted in pretty much every paragraph.

As you might imagine, a famous screenwriter doesn’t write a book about a film critic unless he wants to settle some old scores, and “Antkind” is replete with inside gags and unsubtle swipes. The bearded, 58-year-old Rosenberg is an astoundingly insufferable creation, an Ignatius J. Reilly for the age of Rotten Tomatoes. Preoccupied with being politically correct, B. goes by his first initial so as to not bully the reader with his maleness, and refers to most folks via his own self-invented, non-binary third-person pronoun “thon.” His name might be B. Rosenberger Rosenberg, but he’s not Jewish. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with being Jewish, he just really, really wants us to know that he isn’t. He also can’t be racist because he has an African American girlfriend, who used to play the mom on a ‘90s sitcom but he’s not going to tell us which one. We are assured quite frequently though, that we would recognize her.

B. is a devastating parody of a certain breed of mansplainer who swaddles all his racist and boorishly sexist observations in progressive, campus-friendly language, as if that makes them somehow okay because he’s preemptively acknowledging his privilege. A teacher of cinema studies at the Howie Sherman Zookeeper School and author of more than 50 small press monographs with titles like “Shoah ‘Nuff: The Undervaluation of Lengthy Films in Our Current Fast Food Film Culture,” he also seems to be quite a terrible critic, lavishly overpraising such Judd Apatow films as “It’s Tough Being a Teen Comedian in the Eighties!” and railing against the work of that overrated hack screenwriter Charlie Kaufman. (The passage in which B. waxes rhapsodic about 2006’s lousy, Will Ferrell-starring “Adaptation” knock-off “Stranger Than Fiction” is maybe the most delicious of the book’s petty paybacks.)

Quite accidentally during a research trip to Florida, Rosenberg discovers a stop-motion animated film by a 119-year-old outsider artist named Ingo Cutbirth. The movie is three months long and took 90 years to make, in part because Ingo also animated all the clay figures that were off-camera as well. Cutbirth dies while projecting it for the first and only time to his intended audience of one. But our Mr. Rosenberg fancies himself a modern Max Brod to Ingo’s Kafka, and in the process of bringing the picture to the world, B. accidentally sets it and himself ablaze — those old nitrate stocks could be awfully combustible — leaving only a single frame of film and the critic’s memory of the movie.

His recall dulled by three months in a hospital burn unit, Rosenberg turns to experimental hypnotherapy methods to try and prod his recollections. The problem is that his pesky subconscious keeps bubbling to the surface, so memories of Ingo’s film are interrupted by increasingly absurd digressions spun out of B.’s own hangups and fetishes. This loose structure gives Kaufman license to indulge all sorts of wild non sequiturs and surreal tangents that could never be visualized for a movie camera, with metric tons of prankish, Pynchon-esque wordplay piling up as the pages accrue. I’m honestly not sure how B. ends up injured in a post-apocalyptic civil war started by a fast-food conglomerate and its army of Donald Trump sex robots, but I was amused to find his wounds tended by Alan Alda, still somehow in character as Hawkeye Pierce from the TV series “M*A*S*H.” Ever the cranky critic, B. rebuffs Alda’s assistance and asks instead for Donald Sutherland, who played Hawkeye in the original, far superior movie.

Kaufman’s 2008 directorial debut “Synecdoche, New York” was about a playwright who tried to capture life’s truths by building a replica of his entire world upon a stage, but inevitably that simulacrum needed to contain a stage of its own, becoming a nesting doll of doubles and doppelgängers. The point (I think) was about the impossibility of representing life’s enormity in art, and the protagonist’s failure of imagination in attempting to do so. “Antkind” tackles similar terrain in that Rosenberg is trying to objectively represent a work of art that’s inevitably a subjective experience. Every time B. remembers part of Ingo’s movie it’s different depending on what’s happened to him recently or whatever’s on his mind that morning. Trying to revisit the film in his mind is like that old adage about how you can’t step into the same river twice.

But where the death-obsessed “Synecdoche” was morose and to this writer arduously unpleasant, “Antkind” soars on its own silliness. Throwaway one-liners gave me giggle fits for days, like when Rosenberg mentions a superhero-themed delicatessen called Knishoner Gordon. I also adored the protagonist’s dawning realization that there may very well be an unhappy author behind all his misadventures, as whenever he starts criticizing the work of that overrated hack screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, B. immediately suffers some sort of cartoon misfortune like getting smacked in the face with a plank or falling into an open manhole. (Take that, “Stranger Than Fiction!”)

I always roll my eyes when people claim that critics should somehow be “objective,” as if such a thing were even possible. (I also wonder why they always say “you’re bias” instead of “biased.”) After all, what are we reviewing but our own imperfect memories of the movie, influenced and informed by the baggage and backgrounds that follow us into the theater? Our experiences of art can’t help but include what we bring to it of ourselves, and one of this book’s more telling hallucinations finds Rosenberg imagining Ingo’s film as a blank white screen, all colors in the spectrum blended into one and offered up for the audience’s own interpretation. “Synecdoche, New York” superfan Roger Ebert often liked to quote Robert Warshow’s famous line, "A man goes to the movies. The critic must be honest enough to admit that he is that man." “Antkind” is about that man.