Advertisement

No Ordinary Day: Teachers Help Students Process The Capitol Riots

Just after sunrise Thursday, the four high school humanities teachers at Codman Academy in Dorchester logged into Zoom. They were developing a game plan for how to guide high school students through a conversation about Wednesday’s riot in Washington, D.C.

Even in this virtual space, the energy was high and the mood was urgent. They were trying to work through many questions. What words should they use to describe the people who entered the capitol? Is it ok to show the picture of the man holding the Confederate flag as he walked inside the Capitol? Does it do more harm to show them this violent image of this flag in class? Do they need to see that image to understand this event?

The group decided not to use the image of the confederate flag. They also decided they would all spend the whole class period on the subject. "This was something I knew we'd need to take some time with," said Sydney Chaffee, one of the humanities teachers on the call.

When Chaffee's students logged into class at 10:45 a.m., they had widely varied information. Some had no idea there was a riot at the Capitol building. Others had spent hours watching newsfeeds.

That's a big reason why Chaffee began her class with some context: what was supposed to happen yesterday? What role did those lawmakers play in the peaceful transition of power?

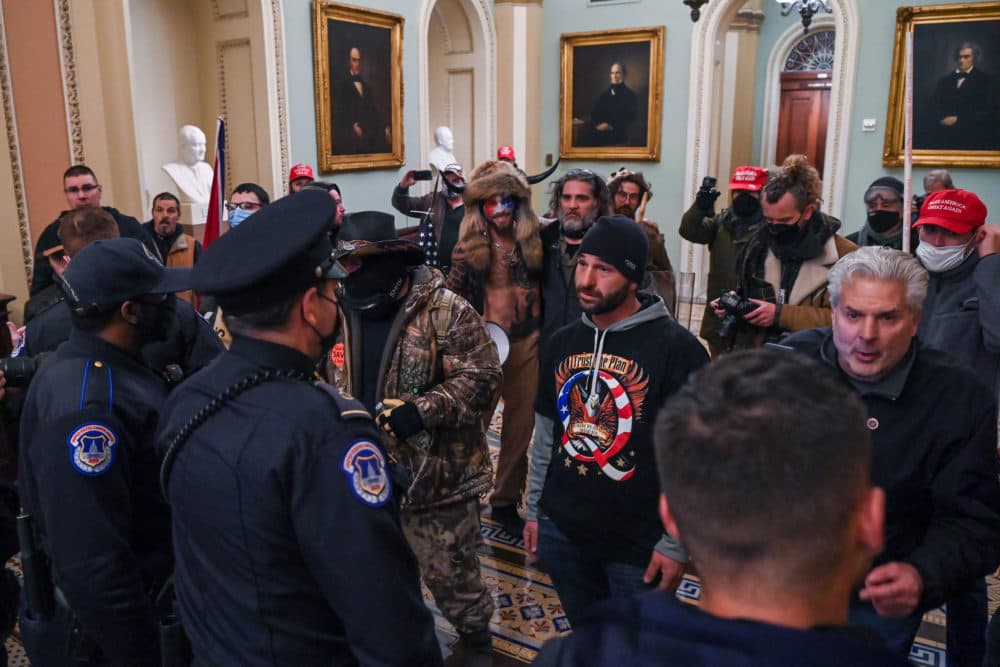

She also wanted to give her students time to reflect. So she showed the class, who are predominantly students of color, some pictures: lawmakers ducking for cover and Vice President Mike Pence resuming the electoral vote count Wednesday night . Chaffee also showed the kids some photos of armed law enforcement officers clashing with protesters in the hallways of the capitol building and outside by the barricades.

It didn't take long for her students to bring up race.

"I asked them, 'What do you notice in the picture? And they said, 'Well, I notice I noticed that the police are not treating them the same way that they treated Black Lives Matter protesters,'" said Chaffee. "'If these people had been Black, they would not have gotten in.'"

Her students were actively engaged through the whole class. Within a few minutes, students were readily volunteering to share their feelings Chaffee recalled, adding that even students who are typically shy in class took the chance to speak.

"[One girl] came off of mute, which she doesn't do very often, and said, 'This shows white supremacy because they wouldn't have been treated that way if they were Black,'" recalled Chaffee.

Even though the students were remote, Chaffee said the virtual environment didn't negatively impact the discussion for the most part. It was a productive hour. But she added, it's still difficult to read the kids' emotions when you're only seeing them as a two-inch square on a computer screen.

Advertisement

For Brittany Jenney, an English as a second language instructor at New Bedford High School, the virtual space offered some unexpected benefits for her students who are at varying stages of English proficiency.

"Students can collaborate and see each other's answers in a written form," Jenney explained.

She added that it's often hard for her students to engage in deep and emotional conversations in class because of language barriers.

"Students are not going to speak passionately about things that bother them in English when they don't feel comfortable speaking in English," she said.

Still, there were some students who got emotional, especially the kids who have been in the United States for a long time.

"I had students who said, 'It makes me feel sad. It makes me feel bad,'" Jenney said. "Several students use the phrase, 'This is crazy.'"

Jenney's students also came to class with varying levels of exposure to the news. She explained the kids reactions also varied depending on their knowledge of U.S. history and governance.

Jenney provided as much information as possible, but there were some questions she had a hard time answering. Like: what will happen to the people who broke into the Capitol building?

"I was explaining to [the student] ... that acts of vandalism and breaking into the building are illegal acts," she said. "But I'm honestly not sure exactly what the accountability is going to look like."

Both Jenney and Chaffee agreed that the classroom discussions weren't about providing students with answers. The most important thing was to simply give kids the time to process what happened and talk with a trusted adult.