Advertisement

The New Climate Bill Won’t Make Or Break A Proposed Biomass Plant In Springfield. But Another State Plan Will

In the week since the legislature delivered a massive climate bill to Governor Charlie Baker, there’s been a lot of talk — and some misconception — about how it will impact a proposed wood-burning biomass plant in Springfield known as the Palmer Renewable Energy facility.

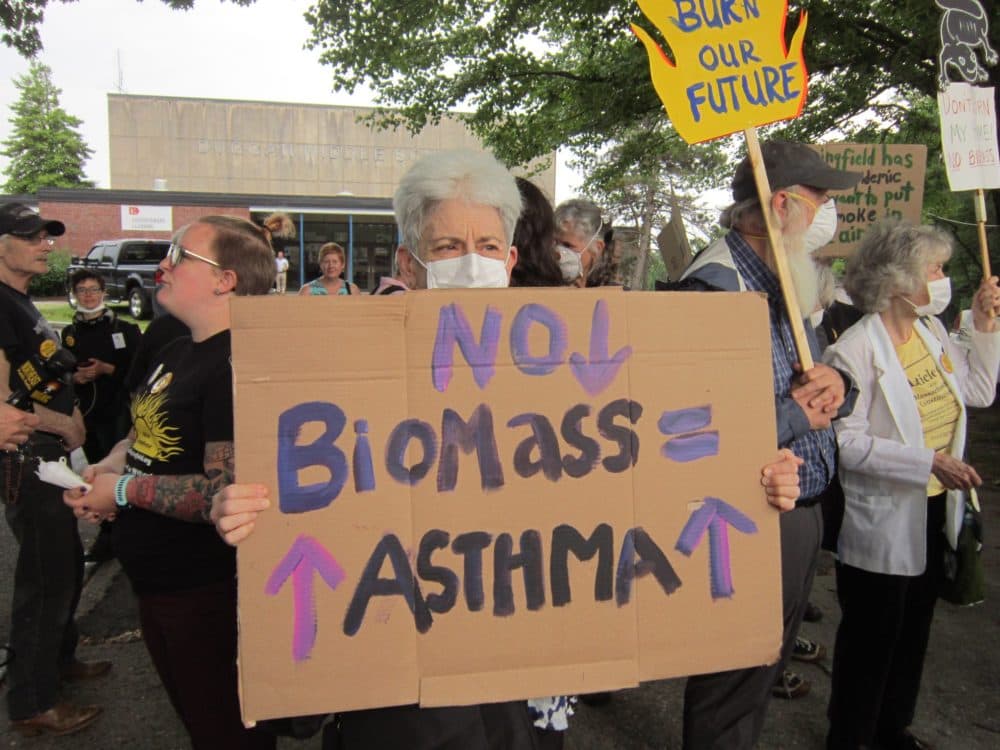

If built, the facility would be the state’s only large-scale biomass power plant, burning about 1,200 tons of wood per day to generate electricity. Biomass in general is controversial, but this plant in particular has drawn criticism because it would emit soot and other harmful pollutants into a city where the air quality is so poor, it’s been dubbed the “asthma capital” of the country by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America.

There has been a widespread misperception that the climate bill contains a provision to stop or delay construction on the plant. It does not. In fact, experts say that the plant’s future probably won't be impacted at all by whether Baker signs or vetoes the bill.

The confusion likely stems from a poorly-worded press release from the bill’s lead negotiators, which said the bill “imposes a moratorium on wood-to-energy facilities of the kind contemplated in Springfield, MA, preventing them from qualifying as 'non-carbon emitting' resources for five years.”

After reading this, many got the impression that the five-year moratorium was a death knell for the project.

“When we saw the bill come out, everyone was saying, ‘Hooray! Great news on biomass,’” says Laura Haight, U.S. policy director at the Partnership for Policy Integrity (PFPI), an environmental nonprofit. But Haight, who follows biomass-related policy issues in Massachusetts closely, knew better.

“I was the bad news bear, informing people that the bill will really have no bearing on whether the Springfield biomass power plant gets built,” she says.

The plant has been fully permitted for years, but construction hasn’t started. Biomass tends to be a risky investment, and without greater guarantees that there will be demand for its power, banks and other financiers are hesitant to loan the company the $150 million it needs to build the plant, says Haight.

This financial calculus is likely to change this year — but not because of the climate bill.

Advertisement

What the climate bill actually means for biomass in Massachusetts

The climate bill affects locally-owned utilities called municipal light plants — MLPs or “MUNIs,” for short. MUNIs act like mini utilities for a city or town, purchasing electricity from power plants and making sure it gets to residents. There are 40 MUNIs in the state, and they account for about 14% of the electricity market.

The other 86% of the market is covered by large investor-owned utilities like National Grid and Eversource. While the state has required these larger utilities to purchase increasing amounts of renewable energy every year, it’s never set similar rules for MUNIs.

The climate bill on Baker’s desk is an attempt to do that — it requires MUNIs to purchase 50% of their power from “non-carbon emitting” sources by 2030, and says they need to get to net-zero emissions by 2050.

In an early version of the bill, biomass was included in the list of “carbon free” power sources, provoking an outcry from environmental and public health advocates. Over the six months it took to finalize the legislation, lawmakers seem to have attempted to strike a compromise between biomass supporters and opponents. The final bill doesn’t remove biomass from the “carbon-free” list, but it says MUNIs can’t count it as "renewable" for the next five years. (It also requires that the state study the environmental and public health impacts of biomass during that time.)

A spokesperson for Palmer did not respond to multiple requests for comments, but told MassLive that the company was reviewing the bill.

“It's problematic in any statute to have biomass defined as non-carbon emitting,” says Haight of PFPI, “but really, even if the legislature had given us everything we asked for, we still wouldn't have had any impact on the Palmer biomass plant.”

Three reasons the climate bill doesn’t impact the Palmer Plant

First, at least 8 MUNIs have already signed 20-year contracts to buy power from the Palmer plant when it begins operations. These agreements account for 75% of the plant’s electricity and are legally binding whether the power counts as renewable or not. Short of banning biomass statewide, the legislature probably can’t do much to nullify these contracts.

Haight says some MUNI operators probably signed contracts with the unbuilt Palmer plant because they thought the state would soon pass renewable energy requirements, and they believed biomass would qualify.

Neither Energy New England (ENE), a municipal light plant cooperative that advises MUNIs across the state, nor the Municipal Electric Association of Massachusetts, which represents all 40 MUNIs in the state, responded to requests for comment. But documents from an ENE presentation show that the organization encouraged MUNI directors to buy electricity from Palmer because it would be a reliable power source that “meets MA Clean Energy standards,” and because they’d be likely to get lucrative renewable energy credits for it.

The second reason the climate bill won’t impact Palmer has to do with the “moratorium.” The bill says MUNIs can’t count biomass power as "renewable" for five years — until 2026. But because they’re not required to meet any benchmark until 2030, the five-year moratorium is irrelevant.

The third — and most important — reason the climate bill won’t impact Palmer has to do with a separate proposal to change how the state awards renewable energy credits, or RECs. It’s a rule change that Haight’s group estimates will make the Palmer plant eligible for $13-$15 million of ratepayer subsidies per year.

The rules that really matter for the Palmer plant

It’s currently difficult for biomass plants in the state to qualify for renewable energy subsidies because burning wood for electricity isn’t a very efficient process. But the Baker administration’s Department of Energy Resources (DOER) is proposing to change that by waiving all efficiency standards for biomass plants that use non-forest derived wood — ie, a facility like Palmer.

A spokesperson for the state says the DOER’s goal is to “streamline” regulations, reduce costs to ratepayers and “address specific policy objectives” like meeting climate goals, but critics of biomass are skeptical.

The DOER “didn’t do any updated forestry or climate science work to get to these new changes. They are just relying on representations from the biomass industry,” Conservation Law Foundation senior attorney Caitlin Peele Sloan told WBUR last year.

In her estimation, if there’s anything that’s going to make or break the Palmer plant — and any future biomass plants in the region — it’s not the climate bill on Baker’s desk. It’s the DOER regulations.

“Those are much more impactful,” she says, because in addition to making the plant eligible for renewable energy credits, they are likely to help the company “get over the financial hurdle to build the plant” by persuading banks that the facility has a strong future.

“If you really look at the rules that the Baker administration is advancing, it's like they were written exactly for Palmer,” Haight of PFPI says. She points to a 2010 letter to the state from Victor Gatto, Chief Operating Officer of the Palmer Renewable Energy company, as evidence.

In it Gatto writes that renewable energy subsidies “are critical for the long-term financing of biomass energy plants like [Palmer]” because it can’t compete in the existing energy marketplace against cheaper power sources.

A recent statement from the Springfield Climate Justice Coalition, which has helped lead the fight against the Palmer plant, summarizes the situation this way: “The new climate bill will not protect Springfield residents and people living in the surrounding cities and towns from the threat of a proposed biomass plant." What will stop the plant is the “withdrawal of the proposed biomass rule changes.”

Where the state — and fate — of the rule changes stand

As required by law, the DOER sent its proposal to the joint Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy (TUE) committee last month for review. The committee is supposed to issue a report and may hold a public hearing in the process. After getting the report, DOER needs to wait 30 days before finalizing the rule change.

Despite public pressure from advocacy groups and Attorney General Maura Healey's office, the TUE has not scheduled a hearing or issued a report. This makes it hard to say when the new rules might go into effect, but if they do, environmental advocates say it’s not the end of the story — they plan to fight the regulation in court.