Advertisement

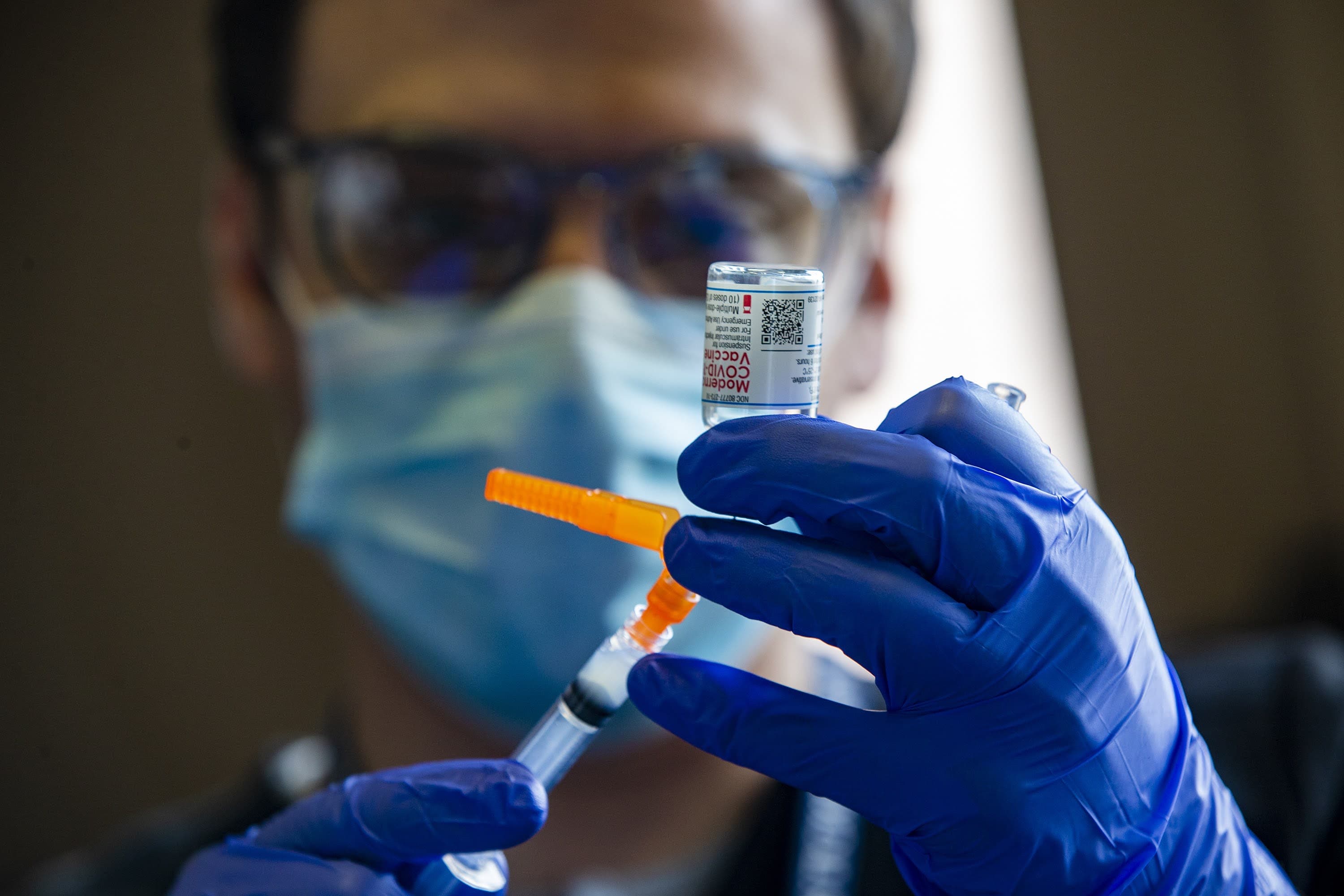

Asked & Answered: Your COVID-19 Vaccine Questions

We know WBUR listeners and readers have a lot of questions about COVID-19 vaccines.

"Are they safe?"

"What are the side effects?"

"When is it my turn to get the first dose?"

While we don't have all the answers, we certainly have a lot of information to help you out. The CommonHealth team, as well as the rest of our newsroom, is working to answer your most frequently asked questions in our weekly coronavirus newsletter. You can find the collection of responses below, updated each week.

Have a question about vaccines? Ask us in the form at the bottom of this article.

Your Vaccine Questions, Answered

What vaccines are available?

A lot of different companies are making vaccines, and most of them use different technologies and methods to work. But right now, only three have emergency use authorization: the Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson vaccines.

Moderna and Pfizer's vaccines are actually very, very similar. Both are given as two shots. They have the same underlying technology — something called modified mRNA. They both target the coronavirus’ spike protein. (And this is actually true about most other coronavirus vaccines.) There are some differences — mainly that the Moderna vaccine is a bit more shelf-stable at higher temperatures. The Pfizer vaccine must be kept at temperatures of approximately negative 70 degrees Celsius (room temperature in Antarctica), and the Moderna vaccine is OK to store in a normal freezer, basically.

Johnson & Johnson's vaccine, which uses DNA sequences instead of mRNA to do the same thing, is a single dose vaccine that can be stored more easily. It's shown to be 66% effective. The really important thing is that this vaccine was still extremely good at keeping people out of the hospital and the morgue.

What are the side effects and how do they compare?

As you might expect, the side effects for the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines are very similar. The short version is that these vaccines are very safe, and while some side effects are extremely common, they’re pretty much the same as many other vaccines we give currently.

I’ll talk about the side effects just after the second dose, as most people don’t have a lot of side effects from the first. The most common side effect for both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines is pain at the injection site, which will likely occur within seven days of the shot. A few people — maybe one out of every 20 — get a bit of redness and swelling.

The next most common side effects are fatigue, headache, muscle pain and chills. A little over 60% who received the vaccine reported these, but so did about 25% of people who just got the placebo. So you can infer that about 35 to 40% of people experience these side effects as a result of the vaccine. These side effects were well tolerated, meaning most people were able to recover easily and weren’t experiencing severe versions of these side effects.

The most common side effects from the J&J one-dose vaccine are pain and redness at the injection site, chills, headaches, nausea, body aches, fatigue and fever for a day or two, NPR reports.

If you experience any of these side effects, the upside is you are extremely likely to enjoy the main purpose of this vaccine: protection against sickness, death and long-term injury from COVID-19.

Should I be worried about allergic reactions?

In very, very rare circumstances, there have been people who suffered dangerous allergic reactions to the vaccine, but the clinicians administering the vaccines were able to successfully treat those reactions. Every time the vaccine is given, a clinician keeps you under medical observation for a period of time to make sure you are OK.

After you get vaccinated, how long does protection last?

The short answer is nobody knows. The only way to know how long the vaccines last is to watch the first people who got them and wait and see if they get sick. Of course, this question is slightly more complicated by the fact that new variants of Sars-CoV2 are zinging around now, so if vaccinated people do begin falling ill, it will take some extra investigating from scientists to find out if it’s because of a new variant or because the vaccine itself is wearing off.

The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are scarcely 1 year old. Moderna started phase one testing on March 16, 2020, so we know that vaccine might be good in terms of protection for at least 11 months. Important note: There aren’t a whole lot of data points on all of this, so take this answer with a mL of saline.

Are you protected in between dose one and two of Moderna and Pfizer's vaccine? And when are you fully protected?

Yes! You are well protected once the first dose begins taking effect. Your immune defenses won’t be built up against the coronavirus until about a week or two after the first shot. Your body needs a little bit of time to start reacting to the vaccine (if you get some of these common side effects, you’ll know it’s working). But from then on, both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines appear to give good protection, about a week or two of “fair to good” protection before you get the second dose.

What does that actually mean? In Moderna’s case, a large portion of their phase three participants only ever received one dose, and researchers who continued tracking them found that the single dose was about 90% effective. For Pfizer’s vaccine, some laser-eyed researchers pointed out that it might be around 70% to 80% effective with one dose.

But that doesn’t mean you should skip the second dose. It boosts you a few percentage points, getting to 90% effectiveness for both vaccines. Once you get your second dose, you’ll be fully protected in two weeks. It's reasonable to hypothesize the second dose will give you a longer duration of protection than just one alone, but right now there isn't data to confirm that. Because this is so new, we don't even know how long protection will last before needing a booster — or if we’ll even need a booster.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine was designed to be just one shot and it looks to be about 70% effective in the U.S.

When getting a COVID vaccine, why are they asking me if I had a positive COVID test within 90 days?

The main reason you're asked that is to find out if you currently have COVID. If you actively have COVID or might be shedding virus still, you could infect others who are waiting in line with you at the vaccine clinic.

The CDC says: "People with COVID-19 who have symptoms should wait to be vaccinated until they have recovered from their illness and have met the criteria for discontinuing isolation."

Dr. Larry Madoff, the medical director at the Department of Public Health, said in addition to the public health threat, if you’ve already had COVID, you may want to “deprioritize [yourself] so that others who have no immunity can get vaccinated first. There is not thought to be any harm to the individual getting vaccinated in that window — you just don’t need it as much as others.”

So, to recap: If you’ve already had COVID, you're in the clear to get the vaccine after following protocols. In fact, you should get it to improve your immunity to COVID. However, some doctors think you could probably afford to wait, if you want to.

What do COVID variants mean for vaccine effectiveness?

This is still not totally clear. When Johnson & Johnson tested its vaccine in several countries with higher concentrations of new COVID variants — including South Africa and Brazil – its vaccine was less effective at preventing symptomatic illness. However, it did prevent hospitalization and death at a rate of 100%. Moderna and Pfizer have both reported their vaccines are still effective against known new COVID variants.

The new variants have mutations on the all-important spike protein. In theory, that could change its shape enough that the existing vaccines wouldn’t work as well on these variants. But as Harvard immunologist Tim Springer told me, a few mutations don’t make new variants very distinct from the original Sars-CoV2.

“One or two mutations on the spike change its appearance very little — no more than a mole on a person's face — so the antibodies will still recognize it fine,” he said.

In theory, one day a COVID variant will rear an ugly spiky head that our current vaccines have no effect on. But the good news is that mRNA vaccines can be adapted very easily to any such new variants, and the FDA promises to be nimble, too.

What percentage of the population needs to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity?

Scientists don’t know exactly, but it’s high. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the federal government’s top expert on infectious diseases, estimated on Radio Boston that it’s between 70% and 85% of the population. That’s low compared to measles, which is so contagious that herd immunity kicks in at about 90%. But it’s high compared to current rates of vaccine acceptance — as low as 50% among nursing home staff, according to state officials. That’s all the more reason, Fauci says, for extensive community outreach to encourage people to get their shots. State officials are not currently offering a time frame for when Massachusetts will reach herd immunity.

Will regulations on safety measures be lifted before herd immunity levels are reached? Can people go unmasked if they have been vaccinated?

It will be months before Massachusetts could get close to herd immunity, and it seems likely that the government will continue to base its safety measures on the daily number of cases detected, rather than the number of vaccines given. Public health authorities are saying that masking and distancing remain very important even after people have been vaccinated, both because the vaccine does not provide perfect protection and because vaccinated people may still be able to transmit the virus. Also, going mask-less is still likely to get you the stink-eye from people who can’t know you’ve been vaccinated.

What medical documentation or approval will I need to prove that I am eligible in this latest phase?

None! However, you will have to fill out a lot of personal information when registering for a vaccine. That includes checking boxes when it comes to a medical history for certain conditions that increase your risk for serious illness from COVID. But this is done entirely on the honor system, so vaccinators will not ask you for any proof of those medical conditions. Does that mean some people will try to fudge their way into an earlier vaccine?

Well yes. People were lying their way to a faster vaccination, although that doesn’t mean you should. The general public became eligible on April 19.

Will the COVID vaccine become mandatory and is that legal?

It already is mandatory for some colleges and universities. Boston University, Brown, Northeastern and Rutgers University have all mandated the COVID-19 vaccine for any student who wishes to return to campus this fall. Of course, that doesn’t mean other schools, institutions or employers will follow suit, but it is definitely a possibility. This isn’t that unusual since schools already mandate certain vaccines. Colleges and universities, for example, usually require meningitis vaccines for matriculation, and state law also requires various vaccines for school children. Massachusetts mandates Tdap, polio, MMR, hep B and chickenpox. So, it's totally legal and expected.

It’s not clear if and how soon it will be before more places start requiring a COVID vaccine. In Massachusetts, Gov. Baker has repeatedly said "no" when asked about planning for vaccine credentials.

Looking at the bigger picture, doses are still in short supply, so requiring vaccinations would put a certain segment of the population on the outside, at least for now. The much debated vaccine passports would do the same. Equity issues regarding who will be able to access what if vaccine passports are widely implemented are top of mind for health experts and ethicists right now. In the short term, it matters a lot because the vaccine rollout has not achieved the level of equity that people had originally hoped for. That's why community colleges in Massachusetts have opted not to make vaccinations a requirement.

In the long term, it means that people who don’t live in higher income countries that have been able to hoard up much of the global vaccine supply will be left behind. And, of course, vaccine passports may face legal challenges in the future. Depending on how they’re implemented, organizations or governments could track you wherever you need to show a vaccine passport, and that's a privacy concern.

How different are antibodies produced after contracted COVID-19 vs. antibodies produced after vaccination?

It’s still not totally clear whether the vaccines create a better immune response than a natural COVID-19 infection – although the vaccines are definitely way safer. This is something that researchers continue to study.

What we know so far is that the vaccines and natural infections elicit high levels of a broad spectrum of antibodies. Unlike natural infections, which make a ton of many kinds of antibodies, the vaccines have a bias for making IgG antibodies, which are durable, long-lasting antibodies typically associated with blood and other tissues. In both vaccine recipients and recovered COVID-19 patients, these antibodies can knock out the virus and protect you from getting sick.

People who were only mildly or moderately sick did not make as many antibodies as those who got a vaccine or were very sick. It also looks like the vaccines produce antibodies with greater specificity to COVID-19, meaning they just hit the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus and not other viruses. The immune response of natural infections looks like it might be able to do some damage to other non-COVID-19 coronaviruses, aka variants. This might help protect those who have recovered from COVID-19 from certain emerging new variants in the future. That being said, many of the vaccines we have now seem to do a pretty good job protecting people against the variants we currently know about.

I have read about the vaccine and herd immunity. I have also read that once you are vaccinated and wait the appropriate two weeks, you can still carry and pass on the virus. So if vaccination doesn’t stop the spread of the virus, how is herd immunity achieved?

The truth is that no vaccine is perfect. In the real world, all vaccines will fail some percentage of the time, and fully vaccinated people can still get sick. We’re not really sure why these “breakthrough cases” happen (variants may play a role), and we’re also not sure how often they happen. Currently, the data suggest that they are very rare. The CDC points out that of the 95 million fully vaccinated individuals, there are fewer than 10,000 reported breakthrough infections. That doesn’t account for the possibility that some vaccinated people might have gotten infected, but remained asymptomatic and were never tested. The CDC says about a quarter of the detected breakthrough cases were asymptomatic.

One thing is quite clear - most vaccinated people are protected from the virus. Of the roughly 10,000 breakthrough cases, only 594 were hospitalized for reasons related to COVID-19. That’s a very small number in the context of 95 million vaccinated people.

This is really important for herd immunity. Picture this: I am vaccinated and you are vaccinated, but you are carrying the virus. First of all, I’m not that concerned that you’ll end up transmitting it to me – especially if you’re asymptomatic – because you probably aren’t carrying that much virus to begin with. So the chances that I’ll actually be infected are lower, especially if we are both wearing masks and distancing! This is really important because an epidemic cannot grow if the virus’ reproductive number – basically the number of people each sick person infects on average – is less than one. But just for fun, let’s say that you do transmit the virus to me. Because I’m vaccinated, there’s a good chance my immune system will be able to crush the virus before it makes me sick. Even if I do get sick, being vaccinated means I am much less likely to get seriously ill.

So to recap: vaccination can lower the odds of passing on the virus if you get sick, which is already looking pretty unlikely. It’s harder for the virus to spread through a vaccinated population because it’s harder for vaccinated individuals to get sick in the first place. Even if vaccinated people do get sick, they’re much more likely to recover without severe illness. And finally, keep on wearing your mask because that just makes it even harder for any funky stuff to happen. And it's a big help for anyone who has a compromised immune system or can't be vaccinated.

Now go get vaccinated! There are tons of appointments available. Bring your friends. Bring your neighbor. Bring your dogs. Your dogs won’t be vaccinated, but they’ll enjoy the walk.