Advertisement

Unexpected Lessons

Interrupted Schooling Meant A Pause In Discipline. For Some Students, That Was A Relief

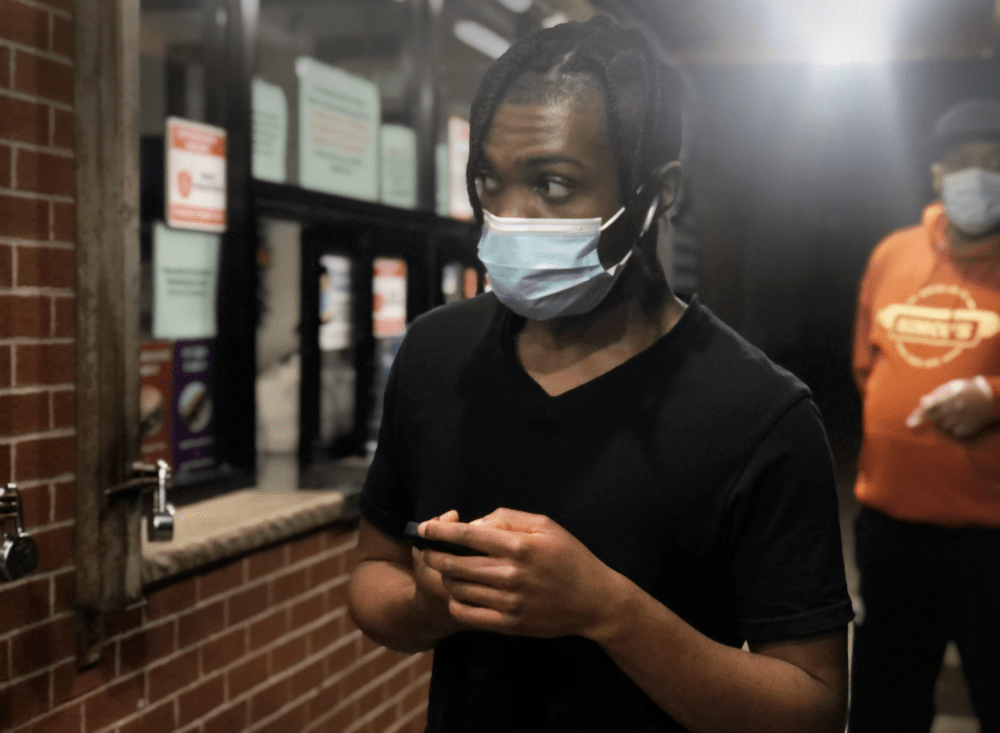

Take away Will Brown’s commute to and from his home on the Dorchester-Mattapan line — and he gets time to think.

“After a school day, I normally go for a walk and just listen to some tunes," Brown says. "Just... refocus myself, you know?”

Brown, a junior at Boston Arts Academy, is still learning entirely remotely. So in the afternoons, instead of a crowded bus from the Fenway, you'll find him walking through his neighborhood and reflecting on his life so far — to a soundtrack of gospel, funk and Afro-Cuban.

His early years, Brown says, were "rough" — he, his mom and his sister were sharing a room in Dorchester.

"I remember days waking up and there’d be no hot water, sometimes there wouldn’t be food," he remembers. "I wasn’t doing very well in school. I can be honest: because of the household I was living in, I always felt angry."

Join WBUR Thursday, May 20, at 6 p.m. for a Cityspace conversation about the losses and lessons of pandemic schooling. The event is open to the public and over Zoom.

That anger manifested in school — mainly at UP Academy Dorchester, where Brown went to middle school — and resulted in what he remembers as "detention every day." He wasn't a menace or anything, he says — just a kind of cut-up. “Teachers knew who I was ... ‘He’s the clown; he’s the one everybody’s going to be looking for, when it comes to making the joke.' "

In the past year during remote learning, Brown says he's been doing "way better," though he's not quite sure why.

"I began to go to bed early and I'm able to wake up. I feel more energetic," he says. "My grades have been above average. I feel like I'm keeping afloat, instead of sinking."

Advertisement

The pause in school, forced by pandemic health restrictions, also meant a pause in discipline — and a sometimes painful cycle of discomfort, mistrust and recurrent misbehavior.

School days were made shorter by pausing that commute, and teachers at the Arts Academy allowed students more free time. In any event, away from the sometimes overstimulating atmosphere and rigid routines of the school day, Brown has learned a lot.

"I feel like I'm keeping afloat, instead of sinking."

Will Brown, junior, Boston Arts Academy

He isn’t alone. The state hasn’t yet published its latest report on school discipline. But Liza Hirsch, a senior attorney at Massachusetts Advocates for Children, thinks she knows to what expect: “a huge drop in the number of suspensions and expulsions ... of course, because the students were literally not in school."

(She notes that there were ways in which discipline mutated into another form online: like muting noisy students in a group video conference or sending them to a kind of digital detention in a breakout room.)

Hirsch, who represents students contending with disciplinary issues, has long wanted to curb the use of harsh measures in response to nonviolent offenses in the state's public schools. But a drop this anomalous year won’t mean much on its own.

Hirsch says some of her clients did have an experience like Brown’s. One young man had been "constantly being punished and reprimanded and disciplined" for minor infractions like wearing a hoodie or having his head on his desk.

That young man, a former client of Hirsch's, experienced the past year as an accidental liberation and was able to graduate — an outcome that had once seemed to be in doubt.

"When the pandemic hit, he actually was able to focus on his work for the first time in a while," she says, "because he wasn’t being repeatedly excluded or dealing with the difficult power dynamics with the teachers at his school.”

That story, Hirsch hastened to note, is not universal: many other young people suffered considerably under the health and financial crises of the past year, along with the social isolation.

But it does serve as evidence for Hirsch's argument that most school discipline is a legalistic solution to a relationship problem. Modify the terms of those relationships — or even just shift them online — and you can get a very different outcome.

Whatever progress may have been made this year, Hirsch does worry that it could largely vanish by the fall. As students return, with academic catch-up as the first priority, schools may not make time to rebuild or support the relationships that make learning work — and discipline could spike as a result.

She's hoping the state avoids that course — and that educators and social workers waste no time. It could start now: reaching out to students and families, especially those who were inconsistent virtual students this year, she says, "not from a punitive standpoint, but from the standpoint of, 'What’s going on in your life? And how are you doing? And what do you need?' "

For Will Brown, this year’s saving grace was that he had some of those empathic, bedrock relationships in place from the beginning, especially with his mentor, Pastor Audi Lynch of the Faithful Church of Christ in Dorchester.

When they met in 2016, Lynch saw a teenager, like him, with Caribbean parents, roots in the church and a passion and talent for music. Lynch knew it all intimately — even the occasional tendency to lose control of his emotions in class.

“I grew up in Natick. And being the only African-American many times in my classroom many times, I’d act out for attention," Lynch remembers. "I was labeled as a problem child — but I was just really creative.”

He went on to Boston Arts Academy, to Berklee College of Music, to touring as well as counseling — a path very similar to the one Brown wants to walk.

So Lynch did some benign deprogramming, informed by his own experience: you’re not a problem child, you’re an artist.

“I’m not the only one, but I made sure in the time we spent together that I was tearing down the labels that were in his mind," Lynch says. "So I think being out of the school for 12 months was the best thing that ever happened to him. Because he didn’t hear that.”

Lynch says he’s tried to get Brown to see his goals — and his musical "greatness" — clearly. (He really is impressive in the only recording he felt was ready to share.) And this year, Brown took him up on it: investing money in his drum kit and time into his craft. He’s now playing gigs and church services several times a month.

Brown’s always had musical dreams. But now they feel a bit more real, and achievable: “Honestly, the drive — I wasn’t always there. I had to develop that, over the quarantine.”

Meanwhile, Brown says he doesn’t feel angry or anxious about a return to in-person classes. In a year of losses, Brown feels like he got a gift.

This segment aired on May 20, 2021.