Advertisement

Three Boston Artists Present Personal Takes On Community At The ICA

In March 2020, assistant curator Jeffrey De Blois was tasked with finding artists for the Institute of Contemporary Art’s “2021 James and Audrey Foster Prize” exhibition, a biennial rite designed to “showcase exceptional artwork and support the city’s thriving arts scene,” according to the ICA website.

The usual studio visits were out since COVID-19 cases were rapidly climbing in Boston. “I had done some studio visits with a few folks in advance of the lockdown, but really the lion's share of my studio visits had to be done virtually, just because of what we were all living through,” says De Blois.

But in the challenge of mounting an exhibit while in isolation, De Blois recognized an opportunity. Why not find artists who are, as he puts it, “platform builders”? In other words, artists who very much defy notions of reclusion, “people who are involved in community, thinking about community and really raising up other people as part of their practice,” he says.

That’s how De Blois settled on Boston artists Marlon Forrester, Eben Haines and Dell Marie Hamilton for this year’s iteration of an exhibit that has happened nearly every two years since its founding in 1999. The show opens Sept. 1.

Each Foster prize winner is already well-known around town. Marlon Forrester is a multidisciplinary artist-in-residence at Northeastern University’s African American Master Artist-in-Residency Program. He is an art educator as well, having taught at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Eben Haines is the founder of the Shelter in Place Gallery, a virtual gallery at miniature scale that he initiated during the pandemic (along with wife Delaney Dameron) allowing artists to continue to put on shows as other galleries shut down. Dell Marie Hamilton is an interdisciplinary artist, writer and curator who works at Harvard’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research and who curated the acclaimed show “Nine Moments for Now” in 2018 at Harvard’s Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African and African American Art.

For this exhibit, the three will address themes that, while collective, also feel very personal.

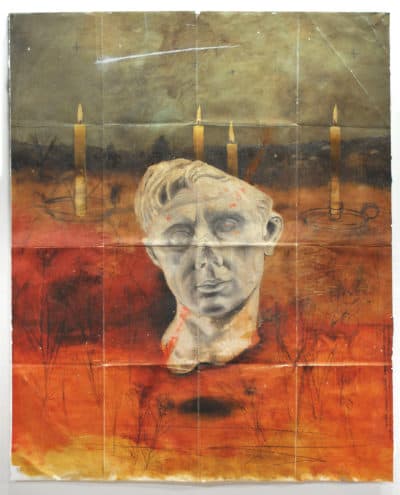

Forrester will show five large-scale paintings inspired by the legend of flying Africans which has circulated for generations among Blacks in the South following a rebellion of captive slaves in 1803 at Igbo Landing in St. Simons Island in Georgia. After gaining control of a slave ship and drowning their captors, a group of about 75 Nigerians destined for a life of slavery walked in unison into Dunbar Creek, committing mass suicide. (Exactly how many were successful remains unknown.) Their real-life act — choosing death over slavery — was both desperate and heroic and led, in subsequent years, to folk tales about Africans with the ability to fly. In “If Black Saints Could Fly 23: si volare posset nigra XXIII sanctorum,” Forrester, whose work has often explored the Black male body and its relationship to power, creates his own exalted Black saints, referencing Western cultural touchpoints such as Chartres Cathedral in France. The geometry in the paintings is derived from the basketball court while the gold leaf, he says, “contextualizes hierarchies around service and freedom, around escape and bondage, around product and ownership, transformation and spirituality.”

Advertisement

Haines, whose paintings often feature sweeping cinematic backgrounds, is creating work in some ways reminiscent of the artifice of his Shelter in Place Gallery. Akin to a theatrical stage set, his installation “Facades” will recreate a New England home that has fallen into disrepair. It will include painting and sculpture and is meant to explore ideas around housing as commodity and a system that he feels prioritizes the rights of developers and landlords over tenants.

“Having grown up in Boston, I've witnessed the rapid redevelopment and gentrification of the city, seeing firsthand what corporate landlords are encouraged to do to rake in profit,” says Haines. “This show is critical of the systems that allow development groups to mine their properties for profit, and the deformed illusions we collectively hold around merit-based housing policies. As rents climb and home ownership becomes increasingly impossible for a majority of Bostonians, it is vital that we reassess our beliefs around community, and why we think it's ok to treat a human right as a financial opportunity.”

Hamilton is also creating an installation, but one based on the possessions she inherited from her friend and mentor Susan Denker, an art historian and longtime faculty member at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts who passed away in 2016.

“Once she left the SMFA, she was a book dealer, but she was very much a hoarder as well, and so was her husband,” Hamilton said in a 2020 interview. “So I got everything from her old take out menus to her maps that she used when she was driving cross-country, to all of her — literally all of her — colored slides. There are thousands of them.”

For this exhibit, Hamilton creates an installation entitled “The End of Susan, The End of Everything,” modeled on the living room, bedroom and study of Denker’s Cambridge apartment. The implicit question: how do we make meaning out of what’s left behind after someone dies?

“There's this accumulation of objects, but also videos that Dell has made of herself performing for the camera, different ideas around motherhood and memory and mentorship that relate specifically to her relationship with Susan, but also sort of putting herself at the middle of an exercise and trying to answer that question about making meaning,” says De Blois.

Admittedly, the ICA biennial has had its ups and downs over the years. Critics have lamented that a museum with global aspirations sometimes seems oddly out of touch with what’s going on artistically right here in town.

De Blois is hopeful that the show will bridge that gap in a moment when the interconnectedness of the global and local has been laid bare through the anguish and misery of a worldwide pandemic. “Cosmopolitan ideas very much exist in this city as well,” he says. “To what extent could the Foster Prize be an expression of what's going on in the world at large?”

The ICA’s “2021 James and Audrey Foster Prize” exhibition is on view Sept. 1-Jan. 30, 2022.