Advertisement

Coolidge Corner Theatre Celebrates Martin Scorsese With Monthlong Retrospective

It’s Martin Scorsese September at the Coolidge Corner Theatre. Last Friday’s late night screening of his nocturnal 1976 masterpiece “Taxi Driver” kicked off a monthlong retrospective originally scheduled for April of 2020. Eight more favorites are to follow from America’s greatest living filmmaker, with “Raging Bull” and “Goodfellas” getting primetime evening slots as part of the Coolidge’s Big Screen Classics series and the other six unspooling after hours in the theater’s “Marty After Midnite” presentations, a time of day perhaps best suited for spending with the director's haunted night owls and antsy insomniacs. (All but “The King of Comedy” and “The Wolf of Wall Street” will be projected on 35mm film.)

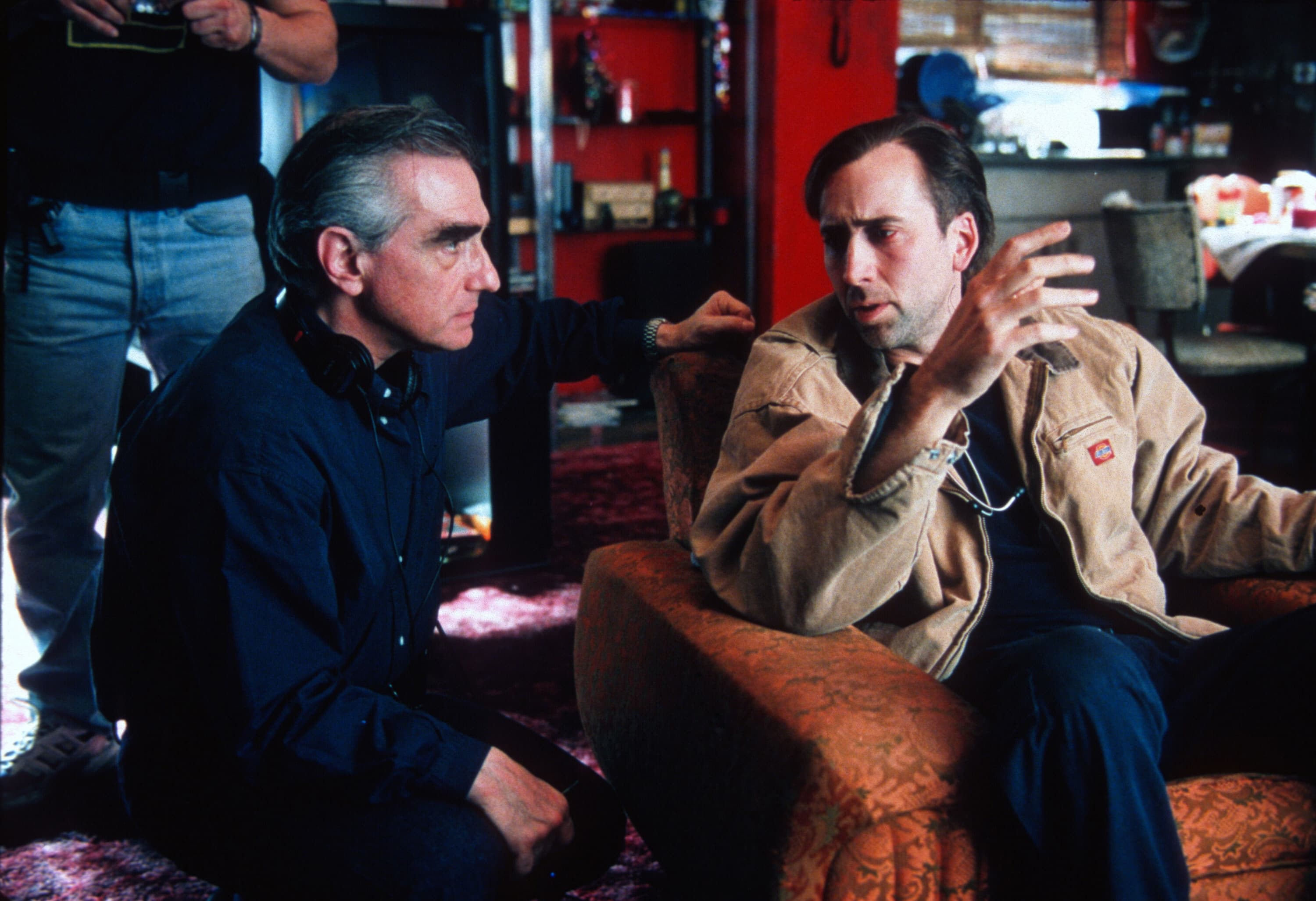

Two of the lesser-known pictures in the Coolidge program actually take place after midnight. 1985’s giddy, exasperating “After Hours” is an anomaly in Scorsese’s canon in that it’s an out-and-out comedy, albeit an extremely nervous one, following an uptight yuppie (Griffin Dunne) stuck in SoHo after a bad date, enduring a surreal series of escalating misfortunes. 1999’s “Bringing Out the Dead” is one of the filmmaker’s most misunderstood and underappreciated works, the soulful, sickly funny story of a paramedic (Nicolas Cage) suffering a nervous breakdown while working overnights in an early ‘90s New York City ravaged by the crack epidemic.

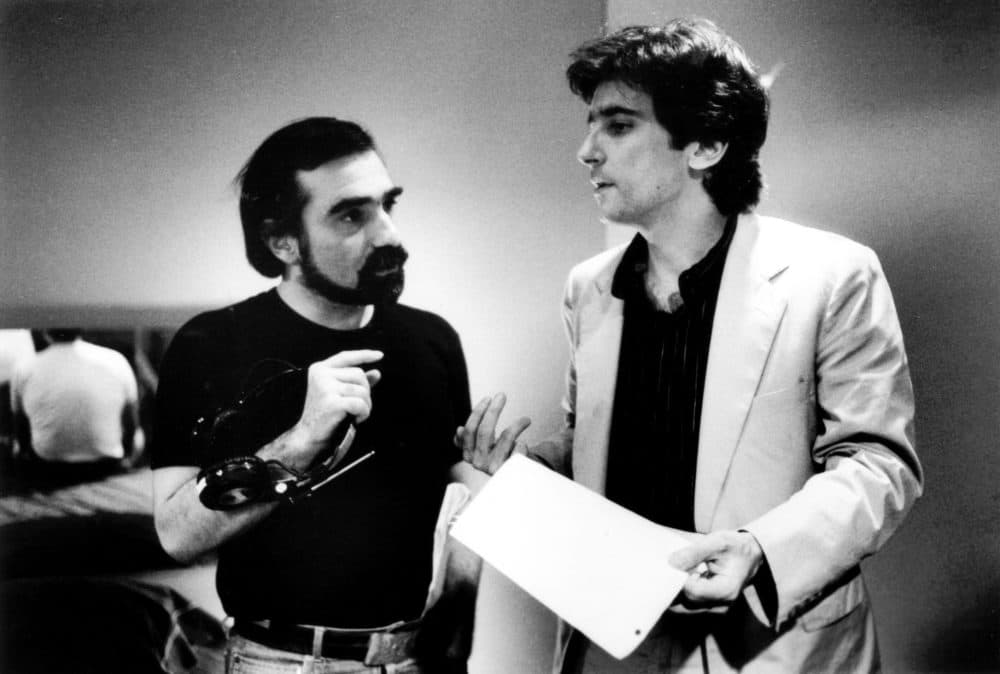

Scorsese was all but finished in Hollywood when he made “After Hours.” Ballooning budgets and cocaine addiction had torpedoed his career, with 1982’s intensely alienating “The King of Comedy” arriving as if to signal its director’s mental and physical collapse, prompting Paramount to pull the plug weeks into pre-production on his dream project, “The Last Temptation of Christ.” (It would be made years later at Universal, but that’s a whole other story.) “After Hours” was a newly sober Scorsese’s spiritual reboot, getting back to his NYU film school roots by shooting a low-budget indie, guerrilla-style on the streets of New York City at night. The screenplay was a class assignment by Columbia University student Joseph Minion, and the $5 million production pulled off for a fraction of the director’s usual budgets.

It’s one of Scorsese’s sleekest, most propulsive entertainments, the camera racing around Dunne’s callow cubicle drone as he’s lured downtown, siren-style, by Rosanna Arquette’s screwball seductress. There’s a clockwork precision to the way things in the movie go from bad to worse, not a line of dialogue that doesn’t double back upon itself as our protagonist finds himself broke and bereft, every attempt to get back to the Upper West Side thwarted until eventually he’s mistaken for a neighborhood prowler, pursued like Fritz Lang’s “M” through these eerily empty streets by a vigilante mob in a Mr. Softee ice cream truck.

The cruelest of comedies, “After Hours” makes me laugh so hard I can barely breathe. Not everybody has that reaction, though. I knew a guy in college who couldn't bear to be in the room whenever we were watching it because the movie made him so anxious, and in his original four-star review Roger Ebert nonetheless confessed, “there was a moment, two-thirds of the way through, when I wondered if maybe I should leave the theater and gather my thoughts and come back later for the rest of the ‘comedy.’’’ Thelma Schoonmaker’s editing is timed to trample on your nerve endings, leaving you all wound up for 97 minutes with no relief.

Some theorize that the film’s deeper meaning can be found in its paraphrasing of a passage from Franz Kafka’s “The Trial,” with what scholars refer to as the “Before the Law” parable now delivered by an aloof bouncer barring Dunne’s attempts to hide inside a punk rock club on “Mohawk Night.” While it’s true that “After Hours” shares the doomy Czech writer’s monolithic paranoia, as far as explanations go I’m partial to an image found inside that very nightclub. Up in the rafters above a chain-link, fenced-in mosh pit where neon-haired revelers slam-dance and try to scalp one another, look closely and you’ll see Martin Scorsese himself, dressed in a general’s uniform and orchestrating the chaos with a handheld spotlight. Then he shines it into the lens, blinding us.

When I mentioned the Coolidge series to my old film school roommate, he said it was ideal programming "because nobody should watch 'Bringing Out the Dead' before midnight." Re-teaming Scorsese with his “Taxi Driver,” “Raging Bull” and “The Last Temptation of Christ” screenwriter Paul Schrader, the 1999 release was one of the season’s surprise box office bombs, rudely written off by critics who were more enamored of fatuous films like “American Beauty” and “The Cider House Rules.” (A writer at the newspaper where I worked at the time took great pleasure in pointing out how “washed up” Scorsese and Schrader were. Twenty years later the two are still doing some of the most vital work of their careers, while I’m afraid the same cannot be said for that particular paper.)

Advertisement

Based on an autobiographical novel by former ambulance driver Joe Connelly, the film stars Nicolas Cage as Frank Pierce, as a burnt-out wreck haunted by the ghosts of all the patients who died on his watch. Unlike his callous co-workers (a trio of scene-stealers played by John Goodman, Ving Rhames and Tom Sizemore), Frank can’t shut off the compassion, overflowing with empathy for the doomed denizens of these mean streets in spectacularly self-destructive fashion. He’s an adrenaline junkie, hooked on the God complex of saving lives and then blaming himself when there’s nothing that can be done. Frank calls himself “a grief mop,” and when we meet him he’s all wrung out.

It might be Scorsese’s most manic movie, with cinematographer Robert Richardson blasting harsh haloes of white-hot light onto the tops of the actors’ heads, cascading down around their shoulders as neon lights blur in puddles on the city streets. Schoonmaker’s cutting is as erratic as Frank’s POV, disjunctively doubling back through dissolves so we’re sometimes seeing things from multiple angles at once. Occasionally the camera flips on its side or upside down altogether, with Van Morrison’s wheezy, queasy “TB Sheets” percolating over and over again on the soundtrack, his wailing harmonica standing in for the ambulance’s siren.

“Bringing Out the Dead” earns its Monty Python-derived title with a sick streak of gallows humor. (Cage even deadpans the “he got better” line from “Holy Grail.”) There are some ghoulishly funny music cues, as when the camera glides above the remains of a tropical fish tank that was shot out during a gunfight, its former inhabitants flopping to their deaths on the floor to the bouncy beat of UB40’s “Red Red Wine.” My personal favorite is when the first responders are cutting loose a drug dealer impaled on a wrought-iron balcony fence, the sparks from their acetylene torch spreading out over the New York City skyline like the iconic opening fireworks from Woody Allen’s “Manhattan.” Scorsese even tosses in a snatch of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” on the soundtrack to hammer the gag home.

Schrader’s screenplay goes hard on the religious references, with characters named Mary and Noel, unspooling the action over three days, like the stretch from Good Friday to Easter Sunday. This mix of black comedy and the Bible sometimes feels like Scorsese is trying to make a sequel to “After Hours” and “The Last Temptation of Christ” at the same time. But, of course, the main text being referenced here is “Taxi Driver,” with Scorsese and Schrader back together 23 years later to tell the story of another insomniac basket case driving around New York City late at night, except this time instead of an avenging angel he’s on a mission of mercy.

It’s a touching attempt by two guys hitting their mid-50s and trying to rework the template that made them famous from an older, more compassionate perspective. (It’s notable that this time around their hero saves the life of the drug-dealing pimp instead of blowing him away.) In Frank’s absolution at the end, we can see the advice Scorsese and Schrader probably wish they could go back and give their younger selves. “Nobody asked you to suffer,” he’s told. “That was your idea.”

"After Hours" screens at the Coolidge Corner Theatre on Saturday, Sept. 11. "Bringing Out the Dead" follows on Friday, Sept. 24.