Advertisement

20 Years Later, Sep. 11 Attacks Can Still Provoke Pain Among Teachers And Students

Today's high school seniors were born after 9/11, which can make it tempting to teach the events of the day as settled history. But this fall, teachers at Waltham High School found that the topic still has to be handled with care.

While the attacks — now a 20-year-old memory — still awaken anger, pain and grief among many adults who lived through them, many Muslim and Asian students say the mere mention of the day can revives bigotry, jokes, and misdirected blame among their classmates.

A 'Difficult' Topic

Waltham High School participates in a national tradition called “One School, One Story." Students and staff read a book and listen to podcasts over the summer. When school resumes in the fall, the story is folded into the curriculum and discussed in groups.

In recent years, Waltham students have read the sci-fi novel Ready Player One, another novel about police brutality, and the story of a naval battle in World War II.

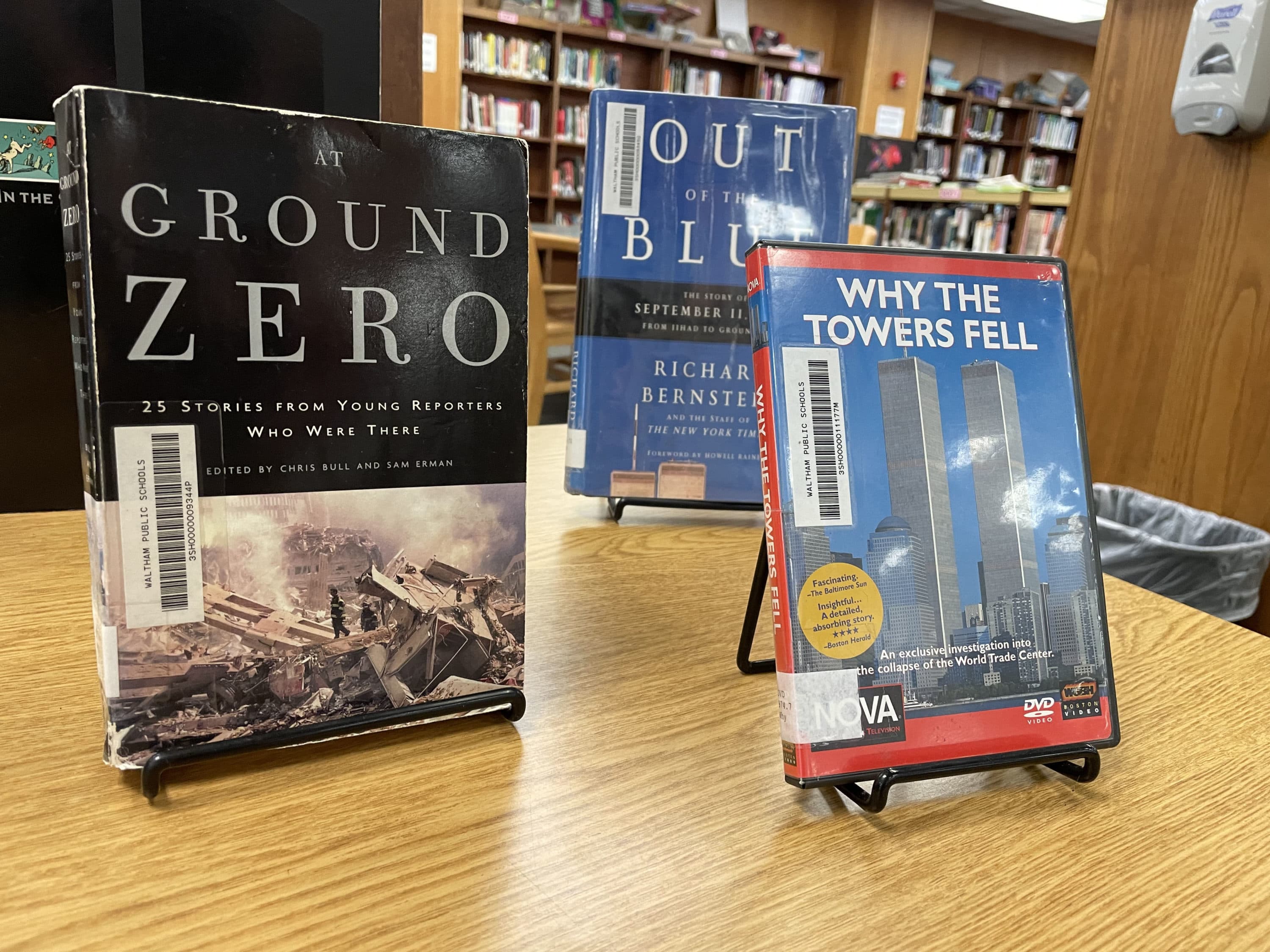

School librarian Reba Tierney chairs the committee that chooses each summer's story, and says they came to Sept. 11 somewhat naïvely last spring. The anniversary was approaching, books were being published and students were curious.

But the choice quickly became complicated. "I don’t think I realized how meaty it was going to be — maybe how difficult," Tierney says.

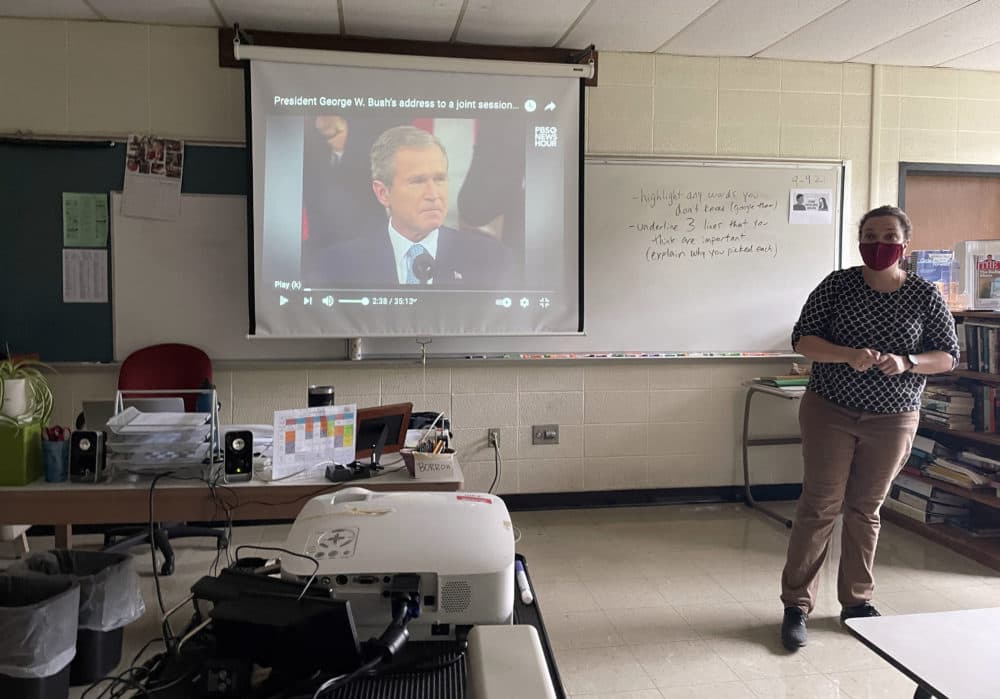

The committee bucked tradition and allowed participants to read from four books over the summer, in part to reflect the complexity of the event. Tierney's co-chair, English teacher Emilie Perna, says they hoped that offering students multiple perspectives would lead to "a more realistic account" of the event.

Two books — "The Red Bandanna" by Tom Rinaldi and "The Day The World Came To Town" by Jim DeFede — focused on acts of sacrifice or heroism in North America during and after the attacks, while he others were centered on the Arab and Muslim experiences of the post-9/11 world: the novel "A Very Large Expanse of Sea" by Tahereh Mafi and "How Does It Feel To Be A Problem?" by Moustafa Bayoumi.

Advertisement

Staff Want Remembrance, Also To 'Learn From Our Mistakes'

Tierney knew several of her colleagues were still grieving or dwelling on that day and its aftermath. Among others, Jean Goodwin Hunt lost her brother-in-law as the second plane struck the World Trade Center; her son — who currently attends the school — was named for his late uncle.

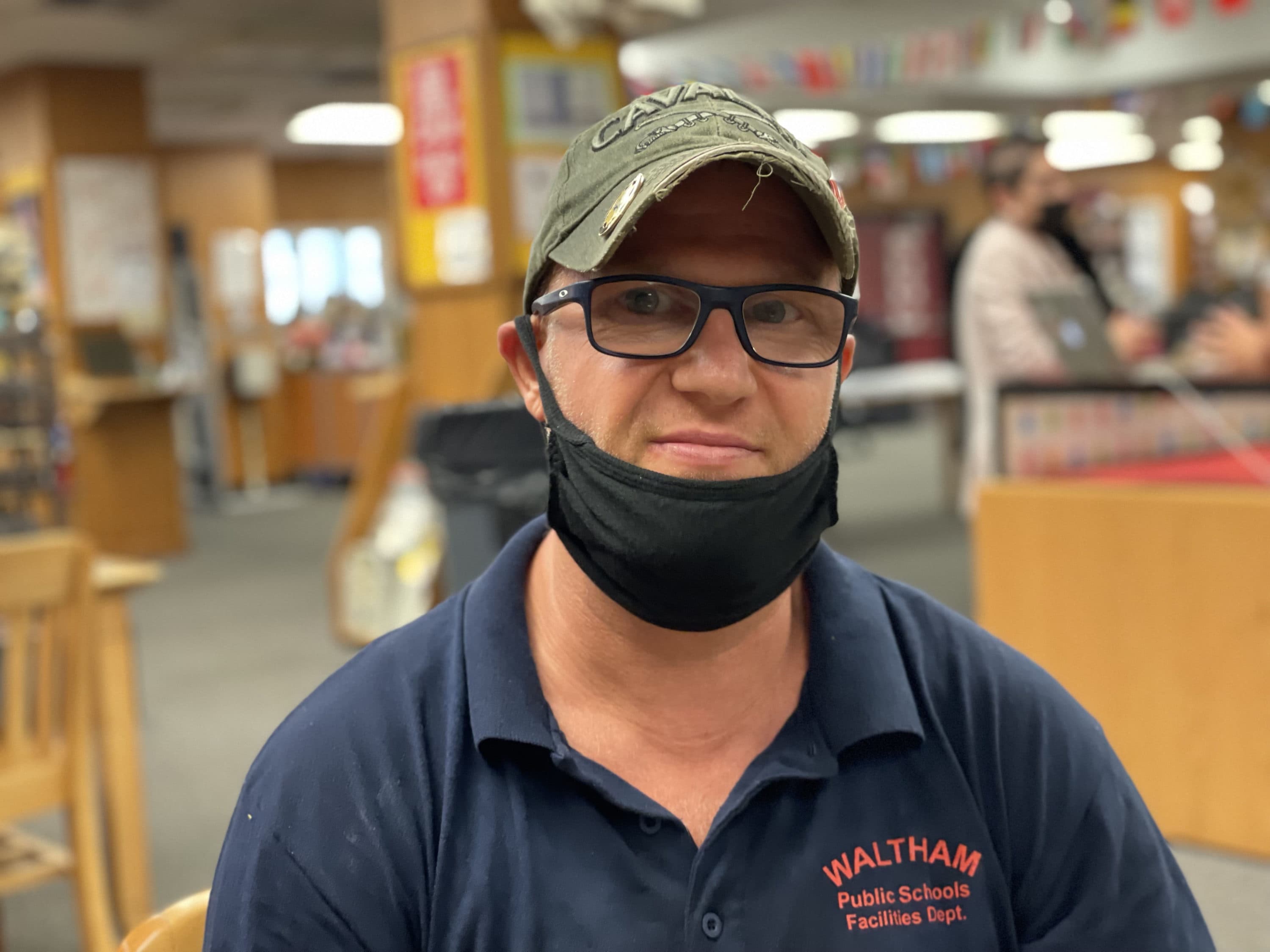

Others meditated on how the event changed their own lives. Joseph Duffy, who sat on the "One School, One Story" committee, is now a custodian at Waltham High. But back in the fall of 2001, he was just a few years past graduation himself.

Within weeks of the attack, Duffy enlisted in the army, pushed on by a swirl of powerful emotions.

He was moved in part by his younger brother's earlier enlistment, which now came with risk. And he was in pain and confusion himself.

"I was angry — sad," he says. "Every feeling you can think of, after that happened, I had that going on."

Duffy says he realizes that similar emotions — felt across the country — played into bias and Islamophobia, hate crimes and surveillance. He says his service in Iraq, and work with the people he met there, opened his eyes to nuances he didn't see in the attack's immediate aftermath.

He hopes this week that students at his alma mater can "live and learn" from September 11 and the nation's reaction: "Learn from our mistakes, from what we did right. We're not perfect."

Students Still In 'The Aftermath'

But some teenaged students bristled at what they thought was too narrow a focus on the topic; Given a choice, many students chose to read "The Red Bandanna," the title that most closely focused on the American experience of the attacks. They also were concerned at how some adults in the school spoke with them about 9/11's impact on their lives.

Junior Mina Alkhafaji remembers one teacher's gloss as, " 'This is ancient history for you guys. Some of you probably don’t even care. This is just something we’re learning.' "

"But for me," Alkhafaji says, "I still have to go through the aftermath of it.”

Alkhafaji and her family emigrated from Iraq to Greater Boston in 2008, when she was 3 years old. Her father and uncle had worked with the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq, and her uncle was killed during the occupation.

Alkhafaji still remembers the sea change — a new sense of otherness — beginning when she first started wearing a hijab to her largely white middle school in Wellesley. She laughs about it now, but ruefully.

“It’s just a piece of cloth," she says. "I’m still the same person. I just put in on my head. But there was definitely a switch — like you could tell.”

Waltham High is more diverse than Wellesley was — with many students foreign-born and learning English — and Alkhafaji says students and staff have generally been more accepting.

But still, Alkhafaji was more or less alone in wearing the hijab for her first few years at Waltham High. (Now a few younger classmates do the same.) And so she knows the era of xenophobic remarks or jokes about terrorism hasn't fully passed away. She and her classmate, Neha Edison, say they appear most reliably on social media but also surface in classrooms.

Edison — who was born in Saudi Arabia but is Christian — recalls making a comment about the American education system in class: "And this kid literally stood up and said, 'If you don't like it here, you can go back to your country.' "

A 'Microcosm Of Society'

Alkhafaji eventually asked Tierney and other staff to discuss the "One School, One Story" decision. The group ended up convening a circle in the tradition of restorative justice: discussing the harm and working toward reconciliation.

Alkhafaji is still "disappointed" that 9/11 will loom so large as she starts her junior year. But she is proud that she made room to discuss the issue, and to make peace with her teachers, including Tierney and Perna.

Tierney gives her a ton of credit for the intervention. "This is a student who took time to try to educate, to make us understand what was happening,” she says.

Tierney says the meeting helped administrators and staff see that the ways in which "intolerance, inappropriate language, bullying online" still happen at the school.

As fall approached, Tierney and other educators took extra care to craft a plan to teach the attacks in all of their complexity. And they asked students and staff to sign a statement agreeing to avoid hate speech and call it out if it occurs.

As they teach the history of the events themselves, they're working to debunk common misconceptions of Islam and its teachings, using a PowerPoint presentation together by Sadia Sharif, a biology teacher who is Muslim. Tierney says, it was a reminder that their large high school is a "microcosm of society," and that teachers have a role to play in facilitating compassionate conversations and something like understanding.

At times, Tierney comes close to saying she wishes they'd chosen something other than 9/11 for this summer’s story. And yet, thanks to Alkhafaji and others, she hopes that this September will yield real learning: painful, but powerful too.