Advertisement

If We Want Everything To Be A 15-Minute Walk From Home, Report Says State Needs To Get Involved

Wouldn't it be nice, housing advocates want you to ponder, to live in a neighborhood where markets, community spaces, transit hubs and a place to satisfy almost every other daily need are within a 15-minute walk from home?

The "15-minute neighborhood" model has been embraced in cities around the world, and parts of the metropolitan Boston area do feature the same kind of connectivity. But without a change in approach from elected officials, researchers and urban planning experts warned Wednesday, that vision will remain out of reach for too many residents across the state.

In a new report, authors with Boston Indicators and the Massachusetts Housing Partnership concluded that a long history of policy choices and hyperlocal decision-making have rendered many neighborhoods segregated, unaffordable and car-centric. Achieving a solution, they said, will require a greater state government focus on zoning, housing development and other fabric-of-life issues.

"It might be surprising to see us focus so much of a neighborhood development paper on state policy, but our view is that we have a wrong level of government problem," Luc Schuster, one of the report's authors, said during a Wednesday webinar. "While jobs, transportation and housing markets increasingly operate at a regional scale, the state has left too many land use and zoning decisions up to local governments, where elected officials represent only small, often quite homogenous town populations."

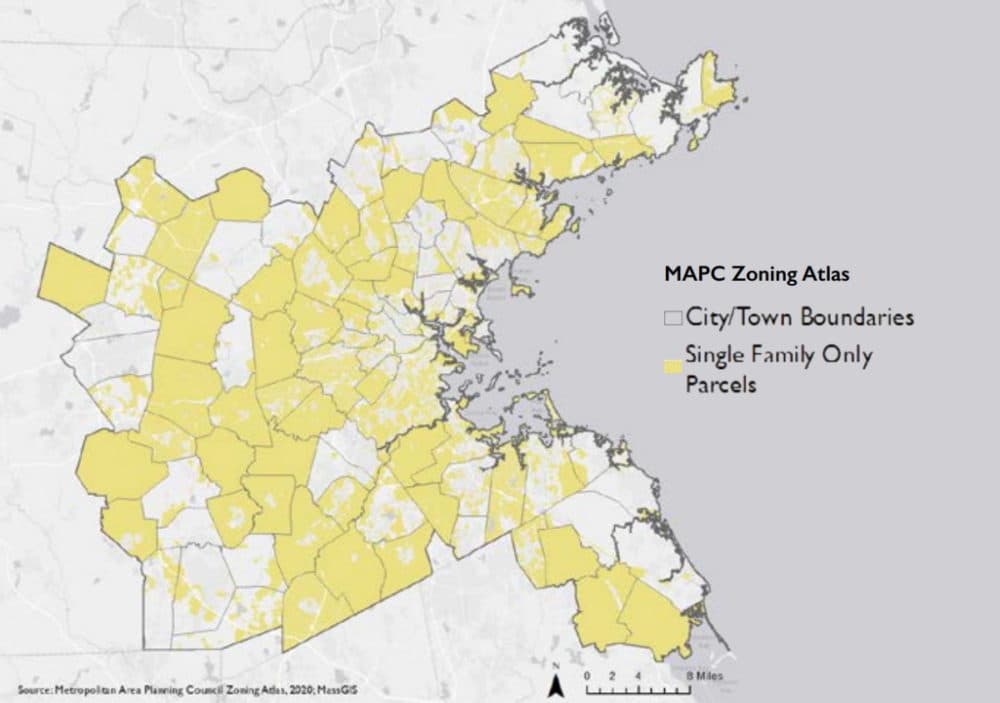

That pattern, researchers said, empowers towns and cities to maintain status quos and limit zoning to single-family homes, even as populations grow and work patterns shift. In turn, residents face skyrocketing housing prices, suffocating highway congestion, and neighborhoods stratified by race and income.

Experts outlined a set of policy changes they believe could help develop more 15-minute neighborhoods, stressing that they believe greater regional or statewide action will be necessary to reverse long-running trends in community development.

"The COVID crisis has gotten people even more open to slowing down and living more locally in Boston and in other cities and towns in the region, and maybe the past year's racial reckoning has opened people's minds up to taking more transformative action to build a more equitable region," said Boston Foundation CEO and President Lee Pelton. "Bike lanes and better sidewalks won't erase systems of inequality or repair racial or economic segregation, but they do open up possibilities."

The 82-page report's proposals include authorizing multi-family housing by right, particularly near transit options, supporting mixed-use zoning to encourage linking residential and business development, and investing in businesses and workforce development in communities of color.

Housing and transit will play a key role in achieving more walkable, interconnected cityscapes and townscapes, authors said. They called for substantial action from Beacon Hill aimed at increasing the state's limited housing supply, particularly for income-restricted units.

Authors noted that an economic development bill Gov. Charlie Baker signed in January requires every city and town served by the MBTA to develop at least one multi-family zoning district, calling it "an important step" to make housing more accessible to low- and moderate-income families.

On the transportation front, Boston Indicators and MHP voiced support for several reforms that have sputtered in the Legislature, including a statewide gas tax hike, higher per-ride fees on transportation network companies like Uber and Lyft, and implementation of a congestion pricing system that alters roadway toll levels based on traffic conditions.

Schuster said the 10 largest metropolitan areas in the United States, except for greater Boston, have some form of congestion pricing deployed on at least one roadway.

"We need to better capture the cost of cars," he said. "There's an interesting debate to be had over whether we should discourage car use or not, but at a minimum we shouldn't do nearly as much prioritization of cars."

Implementing those state-level changes will require significant action from lawmakers, who so far have not signaled that transportation revenue or zoning reform are policy priorities for the current session.

"Where I think we are falling short is really on political will," said Tracy Corley, director of research and partnerships at the Conservation Law Foundation. "We really need to have not just elected officials, but also policies and laws that are made that actually reflect the will of the people, what people say they want to see happen."