Advertisement

MFA returns two looted terracotta objects to Mali

Issa Konfourou paused as he entered a conference room at the Museum of Fine Arts. For the briefest of moments, he stood in silence, taking in the sight of two antiquities stolen from his nation decades ago.

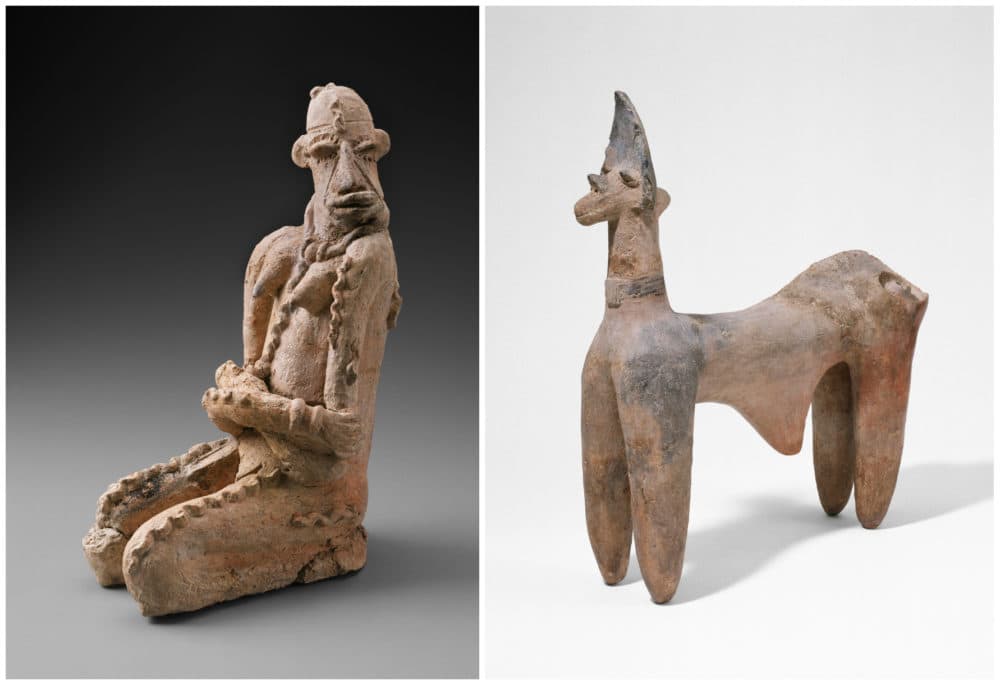

One is a woman kneeling with a necklace, stolen from a burial site near Djenné, Mali in the 1980s. The other, a ewe, was looted from the village of Dary, Mali, around the same time. The two terracotta figures are ancient, fragile artifacts, dating from between the 13th and 15th centuries. They existed long before they were smuggled out of their homeland, becoming part of a private collection in the United States.

“I’m very moved,” he said, quietly. “They are going back home.”

Konfourou, United Nations permanent representative to the Republic of Mali, arrived Tuesday to sign the agreement with the museum to make the return a reality. Both objects were acquired by collector William Teel and displayed at the MFA while on loan in the early 1990s. When Teel died in 2012, they were two of more than 300 objects bequeathed by him to the museum.

Victoria Reed, curator for provenance at the MFA, remembers categorizing these acquisitions, country by country. The two pieces from Mali stood out. “What's sort of astounding about working on these two objects is that there was no attempt in any of the paperwork to conceal where they had come from,” Reed said. “There was no attempt to conceal the fact that they had been looted and illegally exported.”

The return is a long time coming for Mali. In 1998 the New York Times reported the Malian Embassy was trying to repatriate the two items. Malcolm Rogers, the MFA’s director at the time, said that his institution was "not responsible for settling the dispute because the artifacts are on loan from a private collector, William E. Teel.”

Provenance is the history of ownership of a work of art from the time of its creation until the present, Reed said. “It's like a work of art’s biography,” she said. “For many years, I would say that museums and really anyone involved in the art trade bought and sold works of art without asking very many questions about where it came from…people bought and sold artworks, sort of relying on the reputation of the seller. And if it was a dealer you knew and a dealer you trusted. There were no questions asked.”

The ethics of collecting have come under scrutiny in the last 20 years resulting in museums being held more accountable about what is in their collections. Artwork has been returned to its countries of origin, such as Italy, Turkey, and Nigeria. Museums began building their websites and making their collections available to the public, documenting artwork Reed said may have been looted, stolen or forcibly sold during the Nazi era. Last month, the MFA returned the painting “View of Beverwijk,” a landscape by the Dutch painter Salomon van Ruysdael, to the family of Jewish politician and art collector Ferenc Chorin. It’s thought to have been seized during the Siege of Budapest in 1945.

“I think the topic is becoming increasingly important,” Reed said. “It has gone from a sort of no questions asked atmosphere to no stone unturned before you pay money for that work of art.”

Objects like these terracotta pieces are a high risk for theft and looting as there is a strong demand for them, Reed said. The laws in Mali are clear: any archeological materials that are discovered belong to the state. They may not be exported. These two pieces were excavated illegally and were shipped out without proper permits.

The museum first contacted Mali’s Ministry of Culture in 2013. After nearly a decade of communicating back and forth, they will return to Djenné, the town from which they were first smuggled. MFA director Matthew Teitelbaum called the day “deeply gratifying.”

“There was never a lack of goodwill. There was never a lack of intention,” Teitelbaum said. “All I can say is today feels like it's happening in the right way and the right time, and they're going to be welcomed back with open arms and good things are going to happen as a result of today.”

Ambassador Konfourou looks forward to eventually seeing these artifacts on display in Mali’s national museum in the capital, Bamako. “These two objects [were] made for centuries by our ancestors,” he said. “And they mean a lot for Mali and Malians in terms of our own history, our own culture, our own identity and the way we used to live in our country for centuries. I see all Malians, all our history through these two objects.”