Advertisement

Cardinals in, boreal chickadees out: New atlas shows changing bird populations in a warmer Maine

Forty years ago, Maine wildlife officials and local birders joined up to create the first Atlas of Breeding Birds in Maine. The five-year survey documented the range of avian species nesting and raising their chicks here.

Now, the first comprehensive follow-up is nearing completion, and it indicates that since the early 1980s, the complex interplay of global warming, habitat shifts and other factors have brought significant change in the types of birds that are at home in Maine.

Crowd-Sourced Bird Data

From above a snowy dirt road in the Saddleback foothills, two handsome, fluffy-headed gray Canada jays swoop in to inspect Cheryl Ring and Glenn Hodgkins. The binocular-toting bird atlas volunteers are just starting their survey of this area.

"Wow, look right here," Ring says. "That's the Canada jay. They fly, they just float. Wow, whoa."

"They're coming back," adds Hodgkins. "They're landing on the wire right beside us. He's gliding in to say 'hi' to us. You couldn't ask for a better introduction to northern birding than these two coming in. So, sorry if we get distracted here."

Hodgkins and Ring snap pictures of the birds, and note details in a smartphone app that's revolutionized crowd-sourced bird data collection, called eBird. They'll spend much of the day on foot and snowshoe, looking and listening in this "block" of Maine, as they call it.

"The state is split up into blocks of roughly three miles by three miles and there's something like 4,300 of them in the state," Hodgins says. "So a big reason we wanted to come up here was to fill in some of the data for these blocks up here in the mountains on the edge of the boreal forest."

Since the project began four years ago, some 4,000 volunteers have fanned out in search of Maine's birds. Funded with a $2 million federal grant, the effort is also tapping data-crunchers and technicians to conduct thousands of 10-minute audio surveys of localized bird song.

"Using that data we're essentially going to be able to create a heat map. It's going to show us abundance, which is amazing. That's never been done in this state before," says Doug Hitchcox, staff naturalist at Maine Audubon.

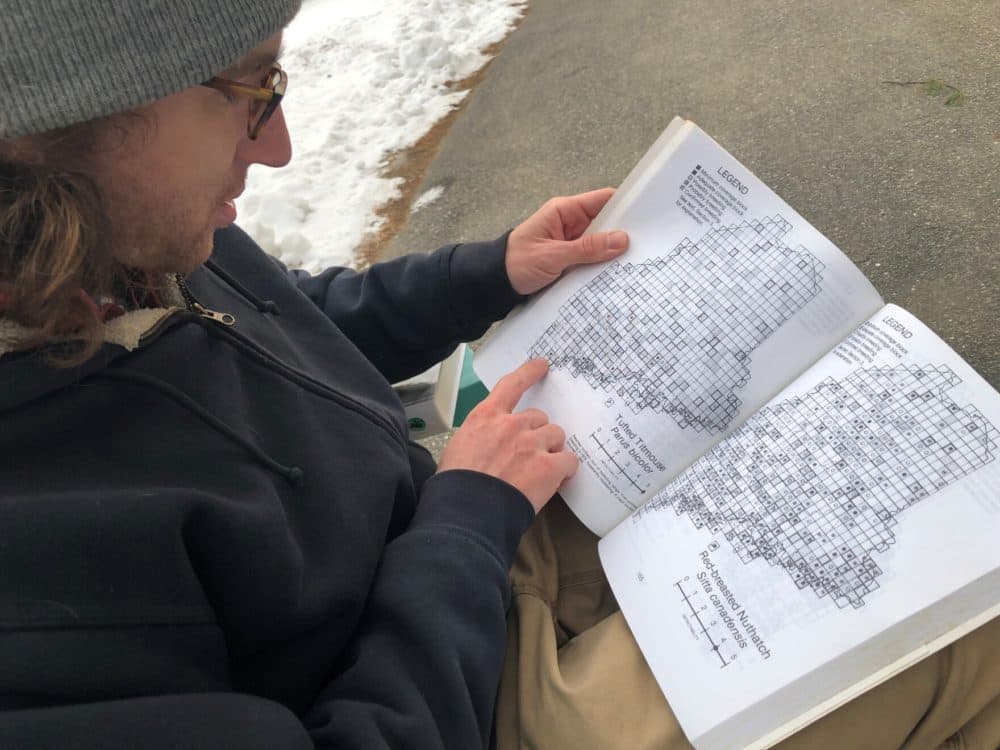

He flips through a copy of the original paperback atlas — its graying newsprint pages charting each species that was found in the state between 1978 and 1983.

"It's these very basic black and white maps. I think all of the data is actually on floppy disks, which was a really fun one to try and figure out how we were going to get that and be able to use it now," Hitchcox says.

He adds that the "really important thing" will be comparing "this snapshot from before and this snapshot now" to see what's changed.

A great deal, as it turns out. And on both sides of the ledger.

How Insect Deaths Affect Birds

There's another year of field-work to go, but some trends that birders have seen in annual counts — and ordinary Mainers have noticed out their windows — are getting preliminary confirmation: traditionally, southerly species such as cardinals, bluebirds, and red-bellied woodpeckers are becoming much more prevalent in Maine's mixed hardwood forests.

They are taking advantage of generally milder winters here to expand their territories. But Hitchcox says it can be a risky gambit — as a growing population of Carolina wrens learned in the harsh winter of 2015.

"There were like back-to-back-to-back nor'easters that dumped a ton of snow," he says. "It almost wiped out Carolina wrens in Maine. They're just trying to find new areas to breed and essentially be the most successful, but it comes with some risks for sure."

While some population trends can be directly associated with warming temperatures, there can be very complex dynamics at work, too.

Take, for instance, what appears to be a significant drop in the local presence of "aerial insectivores" —swallows and other winged acrobats whose primary forage is bugs.

The world and Maine are in the midst of a massive insect die-off, and scientists are only beginning to tease out the drivers, such as increased droughts brought by climate change, habitat lost to development, and accumulating pesticides.

In Maine, the preliminary atlas data indicate the state's population of insect-loving cliff swallows has fallen as much as 70%.

In some cases, says Hitchcox, the timing of insect hatches in Maine may be changing in response to warming temperatures — putting migrant birds like warblers and vireos out of sync with the insect prey they depend on when they arrive here in the spring.

Birds like boreal chickadees may face new competition from relatives like black-capped chickadees, which are occupying ecosystems at higher altitudes as they grow warmer.

And then there are human-driven changes in the landscape, or available forage.

An observed decrease in Maine's population of bank swallows, Hitchcox says, may be driven by changing practices among the state's gravel-pit businesses, which are operating fewer but bigger facilities that are less hospitable for the swallow's embankment dwellings.

"It's more than just climatic changes going on," says Hodgkins, ticking off more possibilities. He says bird feeders can influence the presence of birds, since they can provide food to help them survive cold temperatures.

"Some birds have actually moved from the north to the south, like the merlin," he says. "The merlin didn't used to breed in Maine back in the 1970s and now they're breeding statewide. So why they expanded their range, I'm not sure."

Adrienne Leppold, a leader of the atlas survey at the state Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, hopes it will get Mainers more engaged with the birds around them — and spur action to help them weather climate change's challenges.

"It's really hard when you go out and start paying a little bit closer attention to what's around you, or for that matter, what's not around you, it's really hard to not care more," Leppold says.

Simple actions such as putting out bird feed, or allowing fields to grow longer before mowing can do a lot to tide birds through hard times, she says. Once published, the atlas will include advice on conservation tactics for each species.

"If we can just get people to expand their idea about what they have to offer that can create habitat, we can really provide resources to maintain the biodiversity that Maine has now," Leppold says.

"If we can just get people to expand their idea about what they have to offer that can create habitat, we can really provide resources to maintain the biodiversity that Maine has now."

Adrienne Leppold

So far the atlas volunteers have found all but three species that were seen here 40 years ago — with golden eagles, American coot and tricolored heron possibly extirpated from the state.

And they have documented 15 species that weren't here back then — the kind of finding that brings some joy to birders like Hodgkins and Ring.

"Snowy egrets. There weren't snowy egrets in Maine, not very much. Sand hill cranes, right Glenn?" Ring says."

"Sand hill cranes I think came out from the west," Hodgkins says.

"They just arrived, a lot of birds are showing up — tufted titmice. It's fun to see them but it means something is happening," Ring says.

The atlas project will continue through this summer and into early 2023. More volunteers are needed to help fill out the picture.

As one participant says, you can't protect what you have, until you know what you have.

This story is part of the New England News Collaborative. It was originally published by Maine Public Radio.