Advertisement

The government dropped its case against Gang Chen. Scientists still see damage done

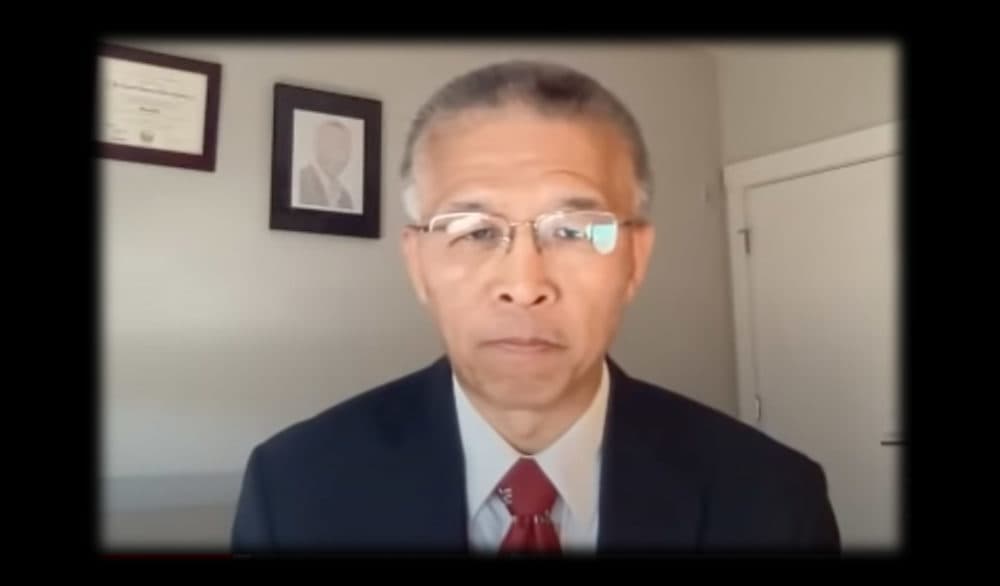

When federal prosecutors dropped all charges against MIT professor Gang Chen in late January, many researchers rejoiced in Greater Boston and beyond.

Chen had spent the previous year fighting charges that he had lied and omitted information on U.S. federal grant applications. His vindication was a setback for the "China Initiative," a controversial Trump-era legal campaign aimed at cracking down on the theft of American research and intellectual property by the Chinese government.

Researchers working in the United States say the China Initiative has harmed both their fellow scientists and science itself — as a global cooperative endeavor. But as U.S.-China tensions remain high, the initiative remains in place.

After the charges against him were dismissed, Chen wasted no time in speaking out about his ordeal: writing editorials, giving interviews and addressing a webinar organized around his case in late January.

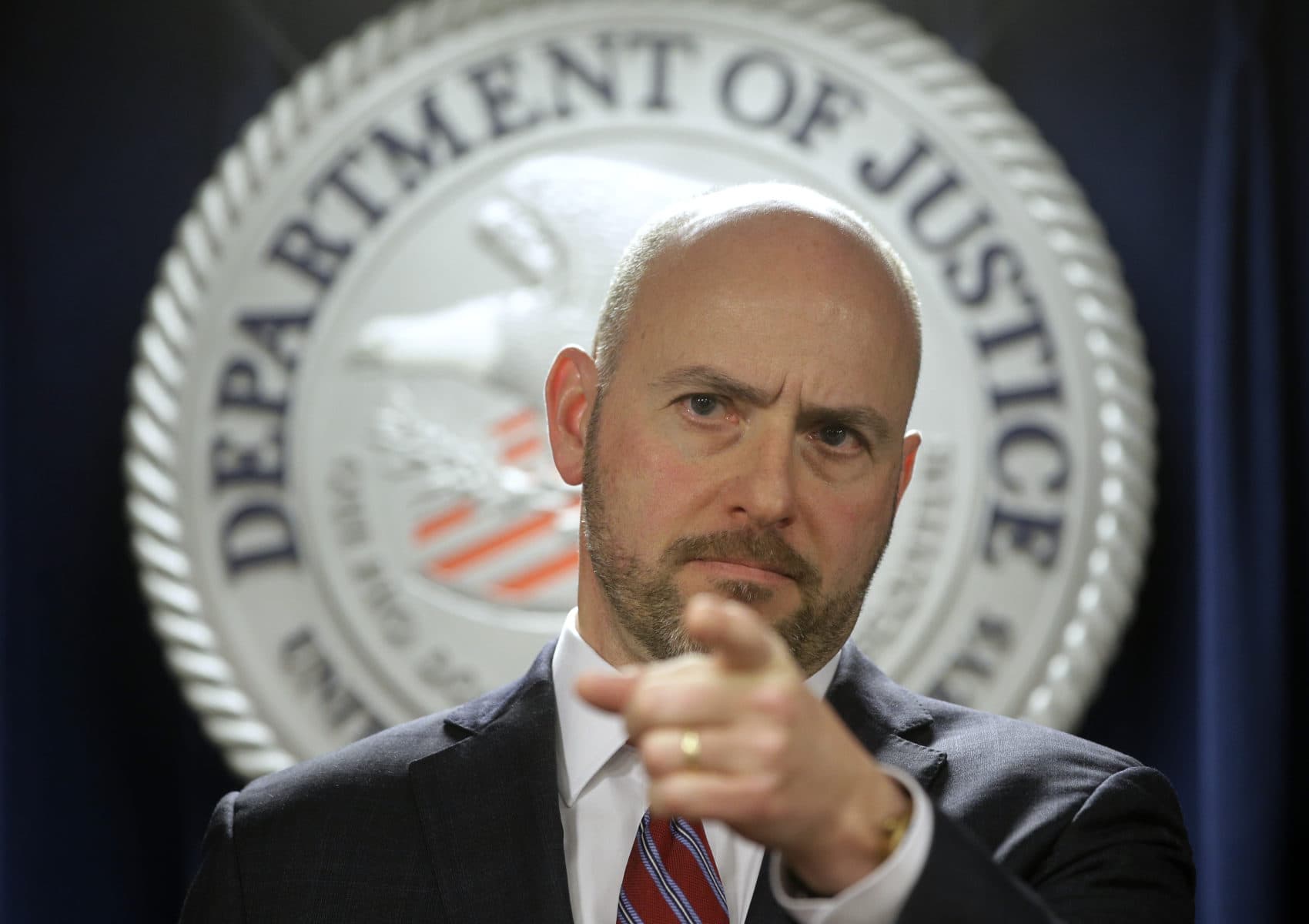

Federal officials say the China Initiative is focused on a critical problem – China’s economic espionage. At a press conference after Chen’s arrest in January 2021, Andrew Lelling, then in his final days as U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts, said “the Chinese government would rather siphon off U.S. technology instead of doing the work themselves.”

Prosecutors never accused Chen of participating in the actual theft or unlawful transfer of proprietary information. But at that press conference, Lelling alleged that Chen’s applications for federal grants made him part of the bigger problem. “This was not just about greed, but about loyalty to China,” Lelling said.

Chen, a naturalized U.S. citizen, argued that the charges against him were based on evidence that had been misunderstood. In dropping the charges last month, Rachael Rollins — Lelling’s successor as U.S. Attorney — said her office no longer believed they could “meet our burden of proof at trial.”

Advertisement

'The Weight'

Chen was not the only Chinese-born academic to go through that experience in recent years, or even the only one to be cleared of all charges pre-trial.

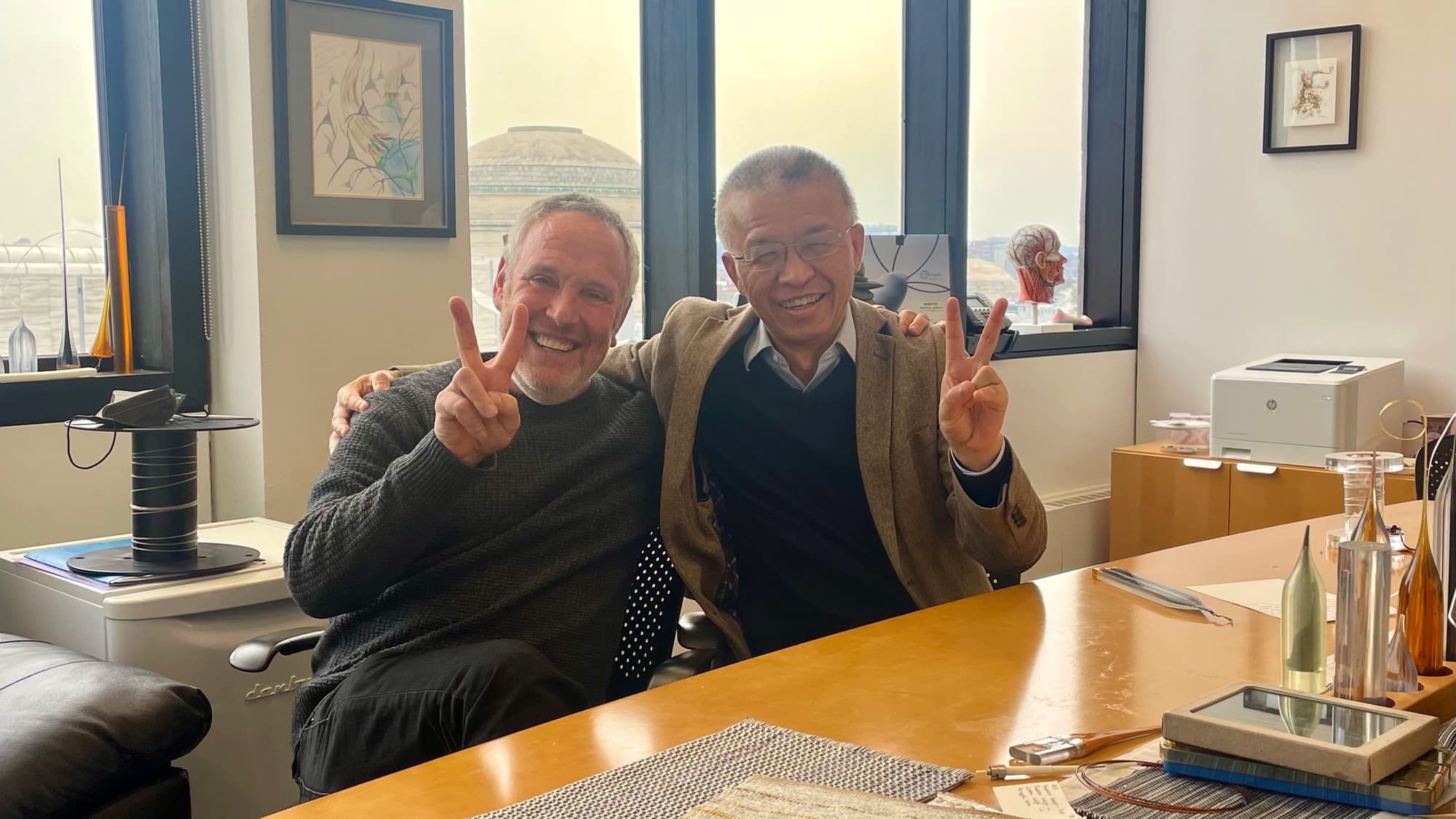

For Xiaoxing Xi, a physics professor at Temple University, the trouble began seven years ago.

Xi came to the United States decades ago in hopes of building a career as a top-flight engineer. He became an American citizen, started a family and joined Temple’s faculty in 2009.

Then, in 2015, Xi was arrested and charged with handing off research secrets to colleagues in China.

“The first time … I saw the indictment against me ... you look at the paper: ‘United States of America vs. Xiaoxing Xi,’ " he said. "I mean just think about it: the weight — the most powerful country in the world against you.”

Xi’s indictment came before the launch of the China Initiative, during the Obama administration. And prosecutors ultimately dropped the case against Xi, but only after his family had racked up hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees.

Gang Chen has said he will never take another research grant from the U.S. government, which doesn’t surprise Xi.

“He won the case," Xi said, "but … this kind of experience has very negative impacts. Your life is different.”

Xi said his own research is “much smaller” since his case was dismissed, as he tries to keep a lower profile. At the same time, Xi filed a federal lawsuit seeking damages that is now on appeal.

Peter Zeidenberg, a defense attorney at the law firm Arent Fox, represented Xi and other scientists in similar cases. He said he’s seen the toll of falling under federal suspicion.

Even if an investigation turns on what Zeidenberg described as “paperwork errors,” employers may assume the scientists, often of Chinese descent, “must be spying for China, or doing something really nefarious,” and fire them.

“I have more clients than I can count who have relocated to China: uprooted themselves, separated themselves from their families,” Zeidenberg said. “These are American citizens — now they’re living and working in China.”

Zeidenberg said he frequently hears from scholars whose past collaborations in China have them “scared to death” of becoming the initiative’s next target.

He said some of them propose reaching out proactively to the Justice Department to explain those collaborations or fill in gaps in the paperwork. “I tell them, ‘Do not do that,' ” said Zeidenberg, himself a former prosecutor. “You’ll become the subject of a new investigation.”

'A Pure Fear Factor'

Zeidenberg said that in his experience, MIT’s decision to “stand shoulder-to-shoulder” with Chen was unusual.

Shortly after Chen’s arrest, MIT’s president, L. Rafael Reif, wrote a letter calling the charges “deeply distressing and hard to understand.” The university paid Chen’s legal fees.

Meanwhile, dozens of Chen’s faculty colleagues organized in his defense, led by Yoel Fink, an engineer who hardly knew Chen beforehand.

Fink said he felt relief after the charges against Chen were dropped: “When an innocent man is freed, it’s a joyful day not only for him, but also for the rest of us.”

But Fink said he’s still angry about the China Initiative and its ripple effects.

“I think we’re going to come to regret this program profoundly,” Fink said. “I think it’s doing tremendous damage to national security. It’s scaring away talent. And it’s instilling fear in the halls of creativity.”

Yasheng Huang, a professor at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, said many promising Chinese doctoral students — who might have stayed in the U.S. in years past — now opt to leave after completing their degrees.

“These are young people; they don’t have this complicated history in terms of collaborations in China. So it’s a pure fear factor,” Huang said.

Last summer, inspired in part by Chen’s arrest, Huang started the Asian American Scholar Forum, an advocacy group that lobbies lawmakers, elected officials and others on behalf of scholars of Asian descent.

Preliminary results from an ongoing AASF survey of 1,300 scholars of Asian descent indicated nearly half had considered taking their research to Europe, Canada or Asia.

Like many in academia, Huang sees a fundamental misunderstanding of “open science” in the Justice Department’s cases against university researchers. While some work at MIT may be funded by corporations and headed to some industry application, Huang said the norm is “basic, fundamental research” — destined for publication.

Huang said the China Initiative has had the unintended effect of slowing down scientific progress of that fundamental kind, pushing scholars toward less public research.

What’s Next?

The U.S. government’s hardline stance on Chinese economic espionage has bipartisan support. Shortly after President Biden took office last year, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said, “China has been willing to do whatever it takes to gain a technological advantage.” The president’s goal, she added, is to “play … better defense.”

But there are signs the administration is weighing changes to the current policy.

Last month, the White House shared a memorandum that sought to clarify the disclosure requirements for federal grants. In it, Eric Lander — the president’s science adviser who has since resigned — wrote that while research security challenges are real, if U.S. policies “significantly diminish our superpower of attracting global scientific talent” or “fuel xenophobia against Asian Americans,” they will have done more damage than any competitor could.

The Department of Justice is expected to issue a review of the China Initiative in the coming weeks. Andrew Lelling, now an attorney in the Boston offices of Jones Day, would welcome it.

Lelling, who helped to shape the China Initiative under President Trump, now says it should be reined in. But he stops short of calling prosecutions like Chen’s a mistake.

“[O]verall … the Initiative succeeded in deterring researchers from hiding Chinese affiliations,” Lelling wrote in an email to WBUR.

He said universities and grant-making agencies have “significantly beefed up their disclosure requirements and compliance protocols.” Lelling concluded by saying, “This success is precisely why [the Justice Department] should now step back on this side of the Initiative — there is nothing more to be gained by continuing to go after researchers.”

This segment aired on February 16, 2022.