Advertisement

Harvard Film Archive reopens with a Flora Gomes retrospective

Two years and two weeks to the day after closing for what we were all told at the time would be a quick quarantine, the Harvard Film Archive at long last opens its doors again to the public on Thursday, March 24. (They’ve held some private screenings for students and faculty over the past few months, but this is the first chance to return for those of us who were too dumb to get into Harvard.) The spring calendar kicks off by welcoming writer-director Flora Gomes, recipient of this year’s McMillan-Stewart Fellowship in Distinguished Filmmaking, for screenings of his five dramatic features.

The 72-year-old, Bissau-Guinean filmmaker studied in Cuba under the legendary Santiago Álvarez and worked as an assistant to French New Wave master Chris Marker, before returning to his homeland to make a series of powerful pictures confronting the legacy of Portuguese colonial rule. But befitting such a long-delayed reopening, we must first start with a party. Gomes’ 2002 “My Voice” is his most joyful and effervescent film, an old-fashioned musical in which the streets of Cape Verde come alive with song. Amid a backdrop of pastel-painted buildings, young Vita (Fatou N’Diaye) fends off silly suitors and dares not sing along with the bustling crowds, as an ancient family curse claims she’ll die if she does.

But after a trip to Paris during which she falls for the very lucky Pierre (Jean-Christophe Dollé) and cuts an album, Vita becomes an international singing sensation. The hardest part is heading home to break the news to her superstitious mom (the director’s companion and frequent collaborator Bia Gomes) in an elaborate revelation that involves faking her own death and a parade of dancing coffins decorated as tropical fish. On the surface, "My Voice" seems a heck of a lot merrier than the rest of the director’s films, and as Gomes explained to a reporter, “Whenever Africa is spoken about or depicted, it is always in terms of the aid we receive, war, people dying of starvation, sick people… I want people to see our Africa, the Africa of my dreams, the Africa that I love… It is a happy Africa, where people dance, where people can speak freely. That is why I made this film.”

As high-spirited as the movie might be, it’s not all frivolity. Gomes slips some sly social commentary into the songs, as when the children of the village yearn for “Nikes and Coca-Cola,” or when Vita is taken aback to discover that the Portuguese who ruled her country for hundreds of years work as servants in Paris. However thin the central storyline, the struggle to reconcile ancient tribal beliefs with the modern world is one that echoes throughout his filmography, going back to his first — and most powerful — picture, 1988’s “Mortu Nega.”

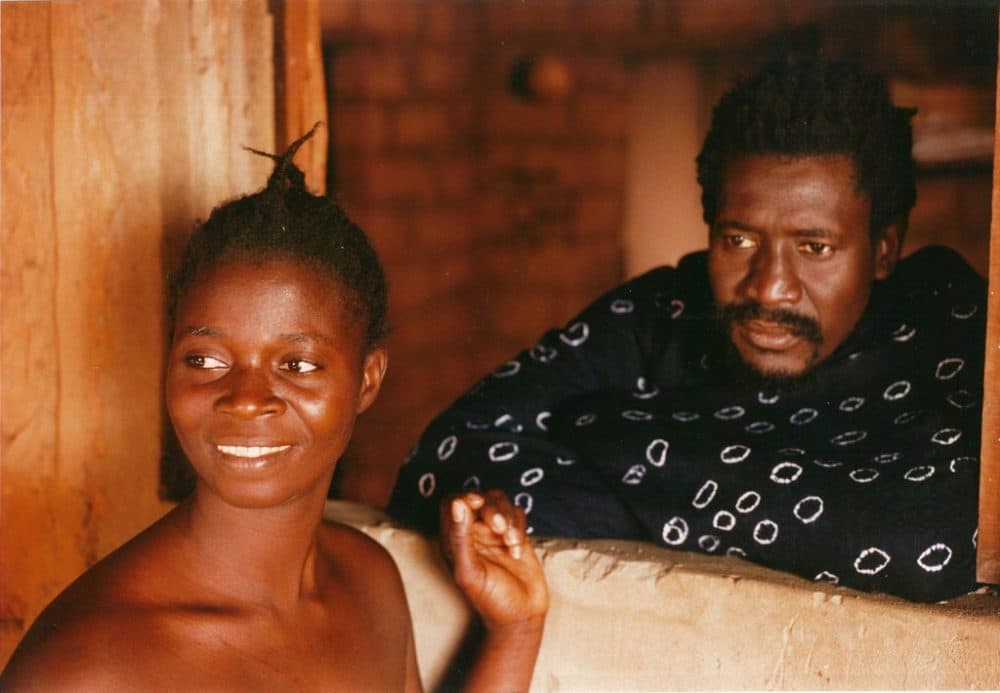

The title translates to “Those Whom Death Refused,” and the first fiction film made in Guinea-Bissau follows Diminga (Bia Gomes again) and her husband Sako (Tunu Eugenio Almada) in 1973, during the waning days of the war for independence. The first half of the film is about the nuts and bolts of revolution, a long process of schlepping goods and guns while traversing treacherous terrain, under the omnipresent threat of Portuguese helicopters. (I can’t help but think the movie was an influence on Steven Soderbergh’s underrated 2008 epic “Che,” which shared a similar focus on day-to-day grunt work.) But the second half gets a bit trickier, wondering how to start a country over again after the war has been won.

Sako aches from an old wound, explaining that he didn’t have time to worry about it while they were fighting but now that he can rest he notices how much it hurts. Gomes loves blunt-force metaphors like that one, summing up these characters’ difficulty in forging a new normal. (The drought doesn’t help things, either.) Such challenges of adjustment are also rife in his wry 1992 romantic comedy “The Blue Eyes of Yonta,” in which a hero of the revolution has trouble with life as an ordinary citizen, revered by younger generations but bereft without a sense of purpose. It’s a genially funny farce about an anonymous love letter and mistaken identities, in which a bridal party is interrupted with a gift of a condom, “so the husband doesn’t bring AIDS into the home.” (That particular present doesn’t go over so well with the guests.) Gomes keeps one eye on politics and the other on the wedding cake falling into the pool.

His 1996 “Tree of Blood” pushes further into the realm of myth, told in the style of an ancient folk tale in which man’s modern deforestation efforts run afoul of a vengeful Mother Nature and a wind that speaks to a selected few. The auto-translated subtitles on the YouTube upload I watched were pretty dodgy so I’m not sure I really grasped all the nuances, but one needn't understand the dialogue to appreciate the film’s stark, startling imagery. And again we have a clash between tribal rituals and contemporary society, contemplating how much of the past we should bring with us into the present.

The series closes with Gomes’ first English-language film, 2012’s heavily metaphorical “The Children’s Republic,” which stars Danny Glover as the only adult in the remnants of a war-ravaged country run by kids who find themselves unable to grow. Full of bold, magic realist devices, like a pair of spectacles that can see people’s future selves and a killer soundtrack by Youssou N'Dour, the film suffers from some of the young actors having trouble with the stylized, poetic dialogue, and it can feel at times like Gomes is trying to cram a few too many out-there concepts into a single film. But what’s powerful about it is something found in every film from this series: A frank appraisal of the ways war stunts the growth of both people and their nations, and how even in independence it's an everyday struggle to persevere.

“The Films of Flora Gomes” runs at the Harvard Film Archive from Thursday, March 24, through Sunday, April 3.