Advertisement

Artist Simone Leigh's work transforms the US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

Several years ago, Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art invited artist Simone Leigh to create works for what would be her first survey exhibition. As Leigh began to work, it was clear that her art was suitable for something even more monumental.

On April 23, Leigh’s exhibition, “Sovereignty,” opens to the public, representing the United States at the 59th International Art Exhibition at the Venice Biennale. During the press conference for the exhibition, Leigh said, “I chose the title sovereignty because I was trying to point to ideas of self-determination — and also to, now, the fourth or fifth generation of Black feminist thought. It’s a very polyglot, complicated thing, but one thing we all agree on is our desire to be ourselves and to have control over our own bodies.”

Reflecting on it now, Jill Medvedow, director of the ICA, says that the museum staff thought Leigh’s work would be “an extraordinary, powerful, wonderful presentation for the U.S. Pavilion in Venice.” And they were right. Leigh was awarded the commission. Her presence there is a feat on its own. It’s especially significant as Leigh is the first Black woman to do so.

Leigh is clear about who she makes art for. Her main audience is Black women. This fact alone is revolutionary when considering the history of the Biennale. The U.S. Pavilion, where “Sovereignty” will be presented, was erected in 1930. “It was the height of Jim Crow and anti-Black violence in the United States. There was fascism in Italy, there was rising anti-Semitism in Europe, and the pavilion is a Jeffersonian neoclassical building,” said Medvedow. The grandeur of Leigh’s sculptures not only entices onlookers but subverts the physical space that holds them.

This year, Leigh has added to the pavilion, creating a thatched roof reminiscent of traditional African rondavels that is held up by wooden columns. The changes she made are striking and create a bold juxtaposition to the Jeffersonian building.

Leigh creates art within a distinctive canon: critical fabulation, a term coined by her friend and collaborator Saidiya Hartman. Much is left out of the archive because of systemic racism, secrecy borne out of safety, and suppression. When considering the history of Black women in America, that hole is gaping. Critical fabulation calls for historians, writers and artists to intervene creatively, and this is precisely what Leigh does with her work. She creates sculptures that fill the gaps by drawing from history, scholarship, and material culture.

“To tell the full truth in the absence of a historical archive requires, I think, the imagination, the power in the art of someone like Simone Leigh,” said Medvedow.

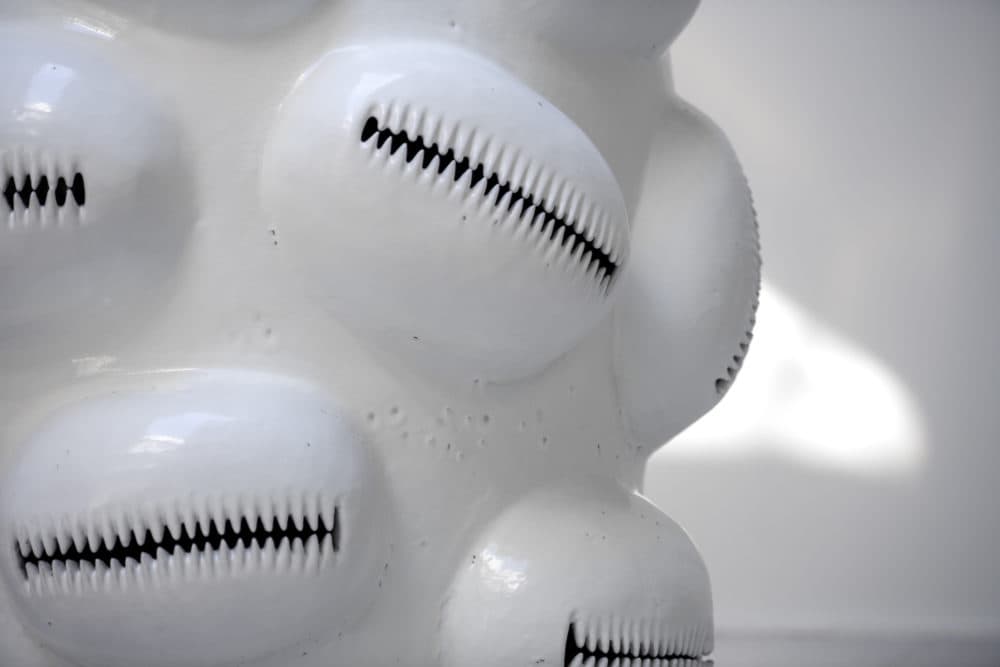

The power that exudes from Leigh’s art is unrelenting. Faceless Black women stand tall, often sporting skirts made of raffia, West African palm trees, and cowrie shells, used as jewelry and decoration across the African diaspora and were once a currency across the African continent. Her ceramic and bronze statues are faceless for a reason — they are not portraiture. This frees up her art, which perhaps is a part of what makes it so visceral.

Advertisement

“What has been written about us is very complicated and often wrong, skewed, or distorted. So, when we are trying to gather information it’s often from someone who had a different intention than what we have,” Leigh said. Her sculptures can be representative of an idea or, in many cases, representative of Black women across the diaspora and what they have done, not what was done to them.

This year’s Biennale comes after a year-long delay due to the coronavirus pandemic and is curated by Cecilia Alemani, the first Italian woman to hold that position in the event's history. The importance of that was not lost on her; this Biennale has more women artists than ever before, many of them women of color. And the main exhibition, overseen by Alemani, is called “The Milk of Dreams” and will place a focus on surrealism and women in the arts.

While the Biennale can be an overwhelming experience for the casual art enjoyer, Medvedow pointed out that even if the viewer knows nothing about contemporary art, the emotion in Leigh’s work and the evidence of her hand can overtake you. If you know about art history, colonialism, or the history of race and racism, you can go even deeper. “It works on both levels,” said Medvedow. “I think that audiences from across the world are going to be blown away by what they see.”